Mark Sheinkman

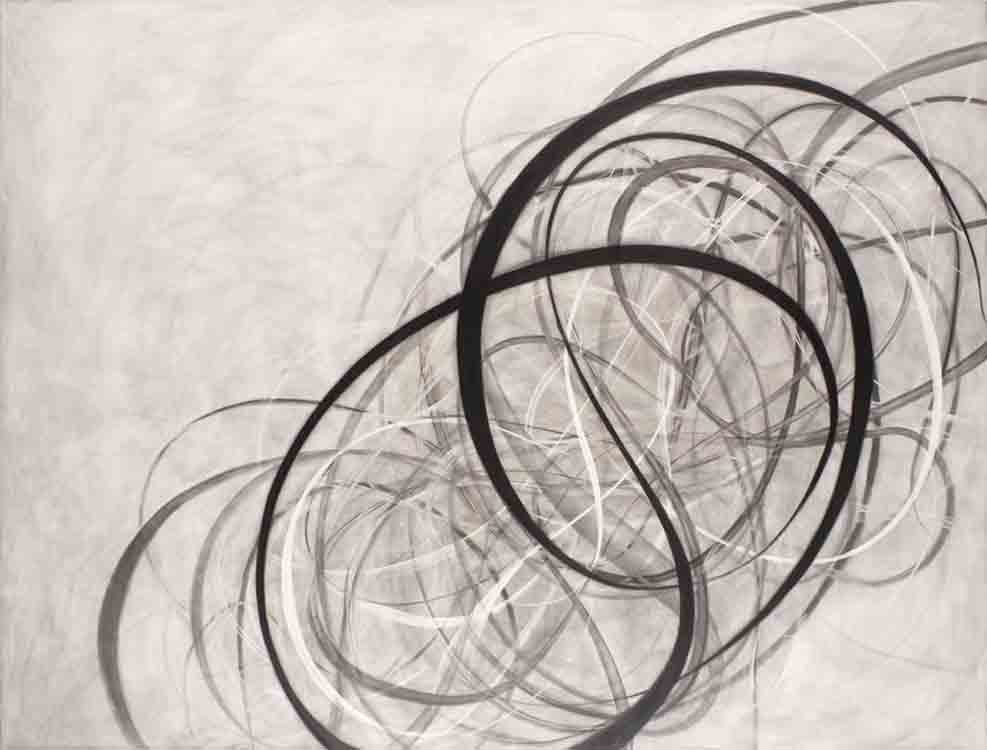

When I first met Mark Sheinkman nearly 20 years ago, he was making drawings with limited means—graphite, charcoal, erasers, and paper—and that choice of the most basic of tools has not changed much in two decades. His works are still predominantly black and white, but now he turns more often to canvases large and small. The abstract imagery has grown both more subtle and more explosive. There is greater depth and three-dimensionality, a bigger scale, and either a mysterious sfumato like a sky full of dancing smoke rings or a contained explosion of starry brilliance.

As he shows me aound his studio, on the far western edge of Harlem, he explains his process. “These are made by making a gesture, usually with an eraser. The ground is oil paint mixed with alkyd, which offers a white surface, though there’s a small amount of yellow to give it warmth. I start with the surface and then very often cover it with graphite. And then I go in erasers and rags and various other tools,”

“It’s about adding and subtracting,” he continues, “erasing the graphite by wiping it away and then adding more. That’s where the layers and the depth come from. These all start with different spontaneous gestures, and then I’ll go back in and make them more three-dimensional. As I work on a canvas, it starts to become more ‘real-looking.’”

Sheinkman grew up in the New York suburbs and spent a year in the Merchant Marine. where he drew compulsively onboard ship and became more focused about where he wanted to go as an artist. After graduating from Princeton, where he studied with formalist critic Rosalind Krauss, he moved to New York and supported himself working in various galleries—such as Gagosian, where he did hand lettering on the walls—and as a maitre d’ at Tavern on the Green. His studio experiments of the time included drawing with a flashlight on light-sensitive paper, and one such work was eventually translated into a billboard in Atlanta. “But I got to the point where I thought, Why go through all the mechanics of going into a darkroom, using chemicals and expensive materials, when I could just get a pencil and a piece of paper and do it more directly?”

In 2000, Sheinkman briefly turned to color when he did a residency at the Lannan Foundation in Santa Fe. “I loved working with color, color is so seductive,” he says. But he was not over-the-top about the results and returned to black-and-white. He showed the color work only to friends. “In the studio I feel like I can try just about anything but in terms of what I show, it’s different. I simply found that by setting limits I was able to experiment more.” (And he is even now experimenting with short videos, which have had their debut in Madrid and Paris.)

In “setting limits,” Sheinkman’s process allies itself with those of earlier generations—the late Kenneth Noland, for instance, spent years painting only concentric circles; Agnes Martin dedicated herself to the grid in many different permutations but usually confined herself to large square formats. The gestural quality of the work, though more subdued than that of his predecessors, also harks back to Abstract Expressionism. Like the mid-century pioneers of American painting, Sheinkman works very much in the moment. “The process is what’s engaging,” he says, “because you’re paying attention all the time.”

Ann Landi

In 2015, Mark Sheinkman had shows at Steven Zevitas Gallery in Boston and Space 2B in Madrid. His work is in the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Museum of Fine Arts Houston. More about the artist can be found at marksheinkman.com.

In 2015, Mark Sheinkman had shows at Steven Zevitas Gallery in Boston and Space 2B in Madrid. His work is in the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Museum of Fine Arts Houston. More about the artist can be found at marksheinkman.com.

Very inspiring.

I love this work, beautiful. Thank you for bringing Mark to our attention.

I first experienced Mark’s work at Lawing Gallery in Houston, which was an incredible space.

Thank you for bringing us into his process and giving these insights into the work of such interesting artists.

Strong and subtle work, very beautiful and also mysterious – i really resonate with the erasure/layering process – creating a field, removing the field, making marks – thank you Mark and Ann

A wonderful overview of Mark’s work. I’ve known Mark since our undergraduate days together, and his intelligence and rigor regarding his work were clear even then. What’s continually amazing to see is how mind-glowingly seductive his work is in person.

Lawing was where I first saw Mark’s drawings also. Beautiful and complex. i own one from that time. Yay.