Marc Baseman

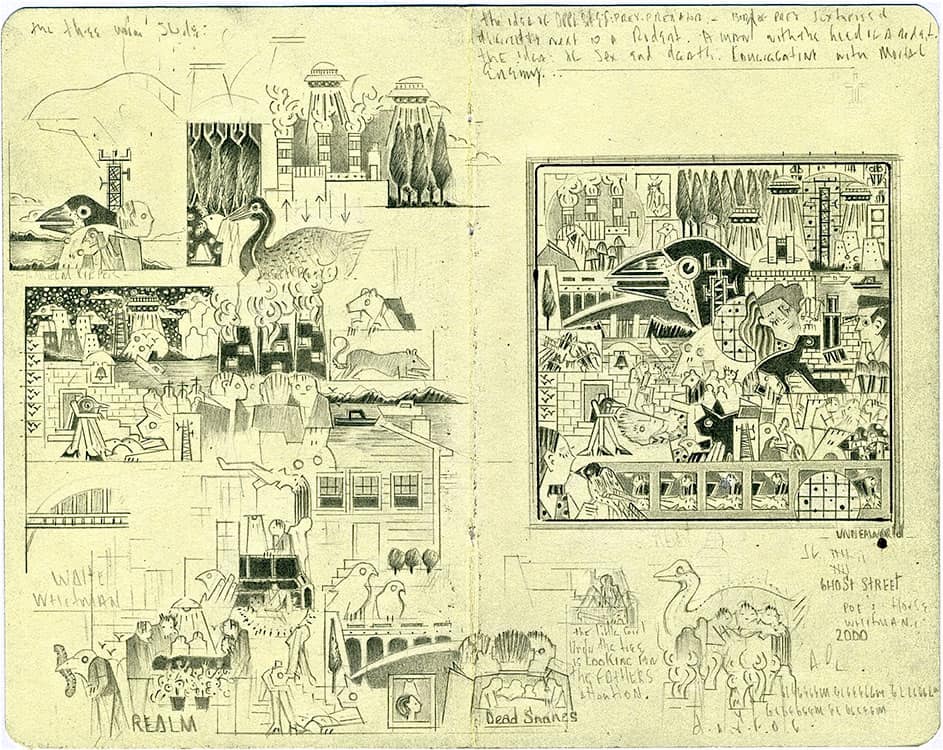

The world according to Marc Baseman is a strange, crowded, and mysterious place. In his tiny drawings—usually less than three inches on a side—a cast of odd characters and objects competes for our attention: birds and rodents, guys in business suits, a naked woman with streaming hair, a kissing couple, crenellated towers, hovering helicopters, space ships, and wide-eyed cats. It’s very hard to say what’s going on, but as one critic noted, “A sense of surveillance recurs frequently [and] Baseman can hint at seamy themes without landing in pulp fiction.”

No matter what their meaning, visitors to his museum and gallery shows pick up magnifying glasses or press close to the framed images to try to figure it all out. The works’ allure is that of a cosmos in miniature, and their closest art-historical forebears may reside in the micro-tableaux of Medieval manuscripts and nutshell carvings of Biblical scenes. With a generous dash of Hieronymous Bosch tossed in to leaven the sanctimony.

Baseman’s “studio” is a corner of his bedroom in Taos, NM, where he is surrounded by the kind of bucolic serenity that never makes its way into his drawings, which are done in graphite on a powdered pigment ground. He was raised in Cheltenham, PA, a suburb of Philadelphia. Though not much inclined toward art while growing up, he remembers being intrigued by glassblowers at the Tyler School of Art and old black-and-white photos documenting the school’s history.

But art school, he says, “seemed too limiting,” and he headed west to the University of Arizona in Tucson. There he studied ceramics for a time but eventually gravitated to painting. “I had no idea how to make a painting but wanted to very badly.” The teacher he cites as most influential was James Davis, who makes large-scale figurative works with a bent toward what might best be described as surrealist expressionism. Baseman recalls him as a “guy who looked like an air-conditioning repairman, but down the street [in his studio] was a body of work that I loved. And it’s not mythological people making this work, but real people. The lesson for me was that I just needed to put my shoulder to it, to get busy, to get started,” The university also boasts an excellent art library, and it was there and in art-history classes that Baseman was blown away by German expressionism, especially Max Beckmann. “That was my way in,” he says.

After graduation, the artist felt he needed to be in a city to pursue his painting, which at the time was on a large scale with ambitious subject matter (none apparently survives, or if it does Baseman is not laying claim to it). He lived in New Orleans and later Philadelphia, and eventually moved to the Bay Area. “I took a job in Napa for the summer, teaching art at a camp. At the end of the summer I had free run of the place, and it was then I realized that it was easier to make my work where there’s peace and quiet.” He also met his wife, Chrissy Rutkaus, and in 1991 the two of them moved to Taos, a place Baseman had briefly visited a few years earlier.

For a time, the artist continued with the big paintings but after the birth of his first son, Max, he stopped for two years. He worked at odd jobs, and describes himself as “the happiest worker you could find because I’d never had a real job and a paycheck. But then it got to the point where I thought, This can’t be my life.” When he returned to the studio, he began making thumbnail sketches for larger works. “That challenge to charge the available space in the most meaningful way possible is still what I’m trying to do.”

When pushed about his imagery, and the characters that often recur in his diminutive universe, Baseman is not exactly evasive but explanations don’t seem to come easily either. Are these a kind of automatic drawing, like the Surrealists pursued in the 1930s and ‘40s? “I never liked that idea,” he says. “I’m not into the whole subconscious thing. I have no problem with Freud or Jung. In fact, I’m a big Otto Rank fan, but my drawings couldn’t be more purposeful.”

For each drawing, the artist makes as many as six or eight sketches, only slightly larger than the finished works, realized on papers he finds in antique shops. Because they are so small—“they fit nicely in my pocket”—he could easily take them to dealers and art fairs when he was ready to find representation about 15 years ago. He has been exhibiting with Dickinson Roundell and Edward Nahem in New York, and Nahem has helped him find an eager audience among collectors in London and Europe.

Baseman keeps businesslike hours, Monday to Friday, nine to five, with an hour for lunch, but the time needed to finish one of his works is as variable as the cast of characters. “I don’t keep track of how long they take to complete,” he says. “Whether it takes twenty minutes or ten years is irrelevant to me. The only thing that matters is the drawing. Everything else disappears.”

Ann Landi

Marc Baseman’s most recent group of drawings was part of a pop-up exhibition (January, 2016) in Venice, CA, curated by David Quadrini of Angstrom Gallery. The artist has no website because he says he’s never needed one. To get in touch with him, or find out more, you can email marcbaseman@gmail.com.

Marc Baseman’s most recent group of drawings was part of a pop-up exhibition (January, 2016) in Venice, CA, curated by David Quadrini of Angstrom Gallery. The artist has no website because he says he’s never needed one. To get in touch with him, or find out more, you can email marcbaseman@gmail.com.

Photo credit: Spain, preliminary drawing (2013), graphite and dry pigment on paper, 4 by 4 inches

Thank you, Ann for your article on Marc as I have two of his drawings which are some of my favorite art works in our collection. His drawings continue to invite me into his wonderful universe and after all these years of living with these beautifully executed images, I see new things in the works. It is always fascinating and interesting to get a glimpse of an artist’s life that you admire.

Very intriguing work. Thank you for sharing Marc. And thank you Ann for the article.

I have collected Marc’s work for many years and never tire of where it takes me – thank you so much Ann! Bravo Marc! Jaquelin Loyd, TAI Modern, Santa Fe

Ann L. – I read the first three paragraphs – introducing me to Mr. Baseman – but quickly became lost and mesmerized by his hypnotizing use of line on paper in the image that followed. I went back to image at the beginning of the profile….one so compact, so inclusive, so exacting, so well executed, so nuanced, so evocative, so mysterious, so storied, so personal, so exciting, so sad, so tragic, so well composed……but always(in the works shown) universally uplifting, funny, philosophical. What can I say? This was a case of the pictures being more magnetic than the words(you wrote)…..though I later read the entire piece you wrote on Mr. Baseman, and, as usual, am impressed by your ability to get to the point! To not analyze or agonize over Art, but tell it like you see it. I like that about your writing.