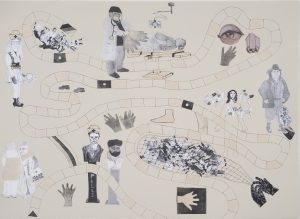

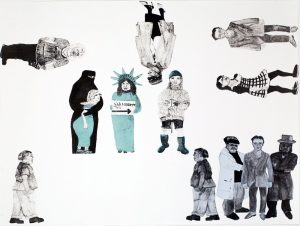

Though not overtly political, many of Leslie Kerby’s projects have addressed social problems with sly wit and a cast of characters who might be the direct descendants of George Grosz. A sampling of works on paper and one video were recently on view at Project ARTspace in New York, where the artist and I met up for a quick tour. In several selections from the show, called “The Laying On of Hands,” a plumply sinister doctor, wearing outsized gloves, figures prominently in indictments of the health-care system. One called the The Safety Net, for example, carries the underlying message that “the general practitioner is a thing of the past,” she explains. “We live in a world where the pharmaceutical and insurance industries hold sway.” A mixed-media collage called Candyland, modeled after the classic child’s game, traces a chain of corruption from poppies to heroin. Game board pieces include the doctor, a couple of dizzy-looking nurses, a patient on an operating table, and a bearded turbaned fellow on a pedestal. Others, she says, “focus on immigration, the feeling of its being like a lottery. One group is in, one group is out.”

An almost sprightly approach to the ills of our times continues in a video animation Kerby shows me when we later arrive at her four-story brownstone in the Boerum Hill section of Brooklyn. Called “The World Contained II,” it’s part of a series in several mediums addressing the strange versatility of shipping containers—”investigating not only their significance in trade for our global economy, but also their use as permanent low-cost housing and their siting as temporary housing in tent-cities or as vessels for risky voyages/passages,” says her website. If that sounds heavy-handed, it’s far from. To the beat of lively syncopated rhythms, rectangular shapes inspired by the containers float across the screen, interspersed with images of ghostly disembodied hands and feet. (The video is being shown at the Visual Arts Center in Summit, NJ, as part of the exhibition “Containment,” through September 9).

The social conscience that inspired these visions took root nearly 40 year ago in Kerby’s earliest jobs after graduation from Randolph-Macon Women’s College, when she and her husband, Jim Kerby, moved to Suffolk, VA, a poor rural community in the Tidewater region. “His position with the local government was to apply for federal grants for sewage and to build a police force. Almost everyone around worked on a farm or in the peanut factory.” She was employed briefly in the peanut factory, too, running a check-writing machine, until she saw an opportunity to become a social worker. “There I was in my early twenties and I was being asked to help people in a variety of situations—from getting new eyeglasses to moving to a new house to preparing for the final stages of their lives.” It was a revelation for a young woman raised in the upscale suburban enclave of Summit, NJ. “Being around people who were truly disadvantaged was a real eye-opener,” she says. “I had to figure out how to be helpful, how to empower them in some way, and that meant entering their lives in on very personal terms.”

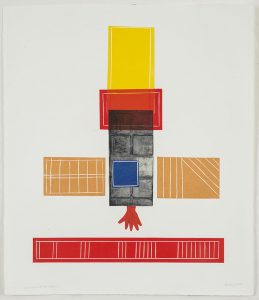

Containment JO U22P1 (2016), monotype with chine collé, plate size variable; paper size, 17 by 15.5 inches

After a couple of years in Virginia, her husband entered business school at Cornell University in upstate New York. Continuing with social work would have meant a battery of exams and a six-month wait for certification. In need of a paycheck to support the couple, Kerby got a position as assistant to the director of development of the Herbert F. Johnson Museum on campus. She was quickly promoted to work on other projects, including exhibition design. She also supervised the guards at the museum, many of whom had PhDs. Ithaca, she says, “was a very interesting place, very laid back, but everyone’s overeducated.”

After her husband accepted a job with AT&T, the couple moved to Clinton, NJ, and Kerby went to work for the Hunterdon Art Museum, developing an educational program and pulling together shows. “My knowledge of art was enhanced by working at the museum, and I took a couple of drawing classes. It was an awakening of sorts, but it would be a while before I recognized that was something I could offer.”

Containment KP U242P1 (2016), monotype with linocut, etching, chine colle, plate size variable, paper size 17 by 15.5 inches

Then, in 1982, when her husband was asked to manage the night operations of AT&T in Manhattan, they moved to Carroll Gardens in Brooklyn, well before gentrification, and Kerby got a job with Saatchi & Saatchi Compton, pulling together market research panels and conducting focus groups for the giant advertising agency.

Her next step, after two and a half years at Saatchi, was to form her own consulting firm, Payne Associates, which worked with graphic design firms and commercial illustrators and photographers. At the same time, she developed a greeting card line, a series of tiny sophisticated abstractions, which evolved into larger collages that attracted the attention of a Brooklyn gallery. “And that’s how I got started,” she says.

When her two daughters were in high school and college, Kerby started working full-time in the studio, a cozy sunlit space on the top floor of her home in the Boerum Hill neighborhood. In the last 25 years, she has more than made up for any lost time, producing videos, prints, paintings, a “Twitter Diary” (“I was imagining what life would be like when we’re in our sixties and eighties and everyone is tweeting”), and even a book of poetry called Peanuts, celebrating the places and people she met in her early years of social work.

Her latest project, which she envisions as encompassing an ever-widening range of mediums, is inspired by cemeteries and looking at graveyards all up and down the East Coast. It’s a reflection on community within the context of death, she says.

“I started considering the community life of the cemetery because we are possibly at a significant moment of change,” she wrote to me. “The Victorian model, a memorial park for the living may have outlived itself. Many communities have physically run out of space and are looking at various ways to use that space with tiered interments, use of grave sites on a temporary and rotating basis, coupled with more people seeking options for cremation, which comes with its own set of variables.” (The Japanese, she notes, have already begun to design “corpse hotels.”)

In her studio hang several mobile-like mock-ups, with delicate upside-down silhouettes of tombstones, human figures, crosses, and trees. These will eventually be translated into sturdier materials, like bass wood and vellum (it can take her up to two years to develop a series, sometimes adding animation or sculpture). “Most of the ideas I’m interested in are complex,” she adds. I can’t capture these in a single drawing or painting. I want to articulate concepts in several different ways that all relate.”

As with her earlier projects, she emphasizes that she doesn’t want to make this one too political. “I’ve always created work around narratives, and I want them to be accessible.”

Ann Landi

Top: “The World Contained II” (2018), video installation shot at BRIC Arts, Brooklyn; photo Etienne Frossard, courtesy of BRIC Arts