Lee Albert Hill grew up in Midland, TX, at a time of huge changes to the landscape and the economy as oil and gas discoveries transformed the small city in West Texas into a booming oil patch. His father, a geophysicist, was “out on the land a lot,” says Hill, who often followed him around as a child. His mother was an assistant to a land man who managed oil leases. But, says the artist, “I could tell right off I didn’t want to be in the oil business. A summer as a roustabout—driving the truck, getting everybody’s lunch—convinced me of that.”

Hill took art courses in high school, working on sets for the theater department, and was ready to pursue a career as an artist when he went off to the University of Texas Tech in Lubbock. But a more practical side of his nature kicked in when he noticed the architecture department housed next door to the art building. “With my artistic ability, I thought architecture would be a better fit and a better way to make a living,” he says. At the time, the curriculum was mostly mid-century Modernism, with “a lot of Frank Lloyd Wright thrown in.”

Soon after graduation in 1986, Hill and his wife made the huge transition to the East Coast, to Guilford, CT, a town on the Long Island Sound that boasts the third largest collection of historical houses in New England. He went to work for an architectural firm that did a lot of projects for nearby Yale University and for private clients in New York. The experience, he says, “was eye-opening to someone who grew up in Midland. There was an exposure to East Coast liberal-arts people and thinking.”

He also went to New York as often as possible and became friends with Sam Weiner, a sculptor with a Duchampian side (he had an alter ego named Evangeline Tabasco) who was very much into Pop Art but also made elegant sculptures in traditional materials. “He opened me up to the possibilities of what an artist could do,” says Hill.

Still, the aspiring artist in him would have to wait until he returned to Texas, to Fort Worth, in 1997. Hill and his wife, Laurie, a physician’s assistant in oncology, by then had decided to have children and wanted to be closer to both their families. Hill dates his beginnings as an artist to Christmas 1999, when his wife gave him both a set of paints and a positive pregnancy test. “She told me, ‘You’ve always wanted to paint, so paint.’”

But, he admits, “it was a struggle to figure out what paint was and what I wanted to do with it. I got a little help from other painters and from gallery owners who would come and critique the work. It took a long time to bring the art and architecture impulses together. The work was very precise in some ways; in other ways, not.”

In 2010, Hill went on a trip to Japan with a group of other architects on a mission to spread the gospel about Universal Design, a movement that aims to make architectural styles accessible to everyone. He visited the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo, where he saw an exhibition called “Sensing Nature,” a series of installations that allowed viewers to experience the art with “their entire bodies in a way that awakens in them the traditional, direct sensory approach to nature,” according to the press release. That, he says, “had a big effect on my art at the time.”

As did works by Aniwar Mamat, an artist he discovered after his return, whose vivid geometric tapestries have sometimes been based on traditional blankets from Xinjiang and left outside to acquire a rough patina from the elements.

When he came back to the U.S., Hill asked himself, “What can I do on canvas based on what I saw in Tokyo?” He started leaving stretched canvases outside for two or three weeks, with washers, wire, and other bits of metal on top. The rust marks, impressions of leaves, and detritus blown on top by nature “became the background for the work I’m doing now, applying paint over the weathered parts of the canvas by hand,” he says. “I was beginning to think about how paint could be something that was not just applied with a brush.”

He still wasn’t satisfied with the results and started looking closely at works by artists he particularly admired. “I really liked Caio Fonseca and began reading anything I could find about him. His father was also an architect and an artist, and we’ve emailed back and forth. He’s very generous about telling me what kinds of tools he uses. His paintings are layered, then fused together.”

Seeking to put his own rhythmic spin on his weathered surfaces, Hill turned to boyhood experiences in customizing cars. “I remember as a teenager watching people paint cars, and I did some car work in high school. That’s where I learned about taping and pinstriping and customizing.”

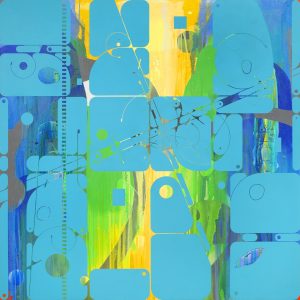

Hill’s canvases are resolutely nonreferential, depending on a vocabulary of attenuated whiplash lines, rounded geometries, and swaths of color, but savvy viewers will recognize references to landscape, especially the manmade landscape as seen from the air. A commercial pilot who came to his show “Forged Paint: Carefully Crafted” at Gallery 414 in Fort Worth this October remarked: ‘Wow! There are even runways here.”

Of late, Hill has been introducing bolder color into the work—bright yellow, creamy blues, and neon orange—and the upshot is painting that is ever more chromatic and lyrical. He still works a full-time job at an architecture firm in Fort Worth, and with two teenagers at home, both with a full plate of school activities, he finds time to paint only late in the evening. “I sleep about five or six hours a night,” he says. “But it’s amazing what you can do in a short amount of time if you just do it every day. It’s when you stop for too long that it’s hard to get back into it.”

Ann Landi

Top: Lee Albert Hill, Liquid Dub (orange), 2017, acrylic on canvas over panel, 48 by 72 inches

Love Lee’s work and the insight gained through this article!

Thank you Bill!