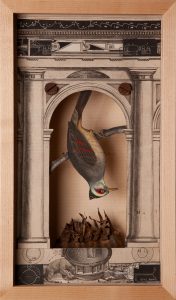

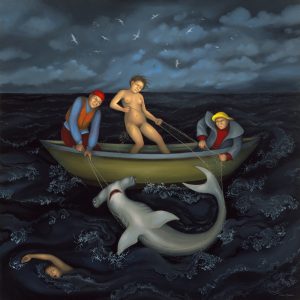

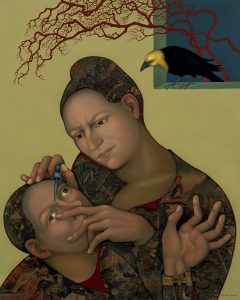

Julie Speed’s paintings offer up a magical and mysterious cosmos that defies literal interpretation. A pair of sailors and a naked woman wrestle with a hammerhead shark trapped in a net. An exuberant baby leaps from his mother’s lap as a tornado churns outside an open window. A frowning woman tenderly places drops into the eye of another figure, possibly female, as a yellow-headed bird looks on from a window ledge. Certain motifs recur: the shark and sailors, for instance, along with accordions, bears, birds, and skulls.

The savvy viewer will catch the references to art history: Japanese prints, the 19th-century French engraver Gustave Doré, Renaissance artist Antonio Pollaiuolo, and the late Medieval French painter Enguerrand Quarton. To add to the puzzlement, some characters have an extra arm or third eye; the latter, in particular, can induce a certain queasiness in the viewer, like the double vision after one too many beers.

If Speed’s works are not like anything else out there—neither straightforward illustration nor campy realism in the manner of Lisa Yuskavage and John Currin—it’s possibly because she has been a maverick from an early age. “From the time I can first remember, my ambition was to be a caveman. Even then I knew it was better to be a caveman, not a cavewoman,” she says. “After the caveman phase, I wanted to be a pirate” But all along, she adds, her end goal was to be an artist. “I didn’t really have any other career choice.”

Her family moved often, from her birthplace in Chicago to various towns in Connecticut, as her father, an inventor and engineer, accepted different jobs around the country. Wherever they settled, making things by hand was always an important aspect of the household. “Both my father and grandfather built model ships from scratch,” she recalls. (In another interview, she noted that “everyone in my family were sailors or descendants of sailors.”) Her mother was an expert seamstress, who also hooked rugs and knit sweaters, and together mother and daughter designed imaginary buildings on graph paper. “None of this was called art,” she says, “and we didn’t have art books in the house.”

But there were nonetheless significant stimuli to spur a child’s imagination: a book of the world’s religions that had a foldout page of Indian gods and goddesses and a reproduction of Michelangelo’s paintings for the Sistine Chapel. And in the catalogue essay for her forthcoming show at the El Paso Museum, she recalls an elderly great aunt who told marvelous fairy tales which “often revolved around impossible tasks and quests that easily could end with a phrase like ‘and so the Shark King ate the lovely princess.’”

“I started drawing as soon as I could hold a pen,” Speed says. “I was twelve when I sold my first drawing for twelve dollars in a bookstore.” During summers as a teenager, she worked with Anne Jones Fuller at the Stonington Art Gallery, where she encountered the works of Fairfield Porter, Jane Freilicher, Neil Welliver, and Jean Jones Jackson. “I would meet all these amazing people, like Claire Booth Luce, and avant-garde artists from New York,” she says. “All the time I was there I was doing my own work and showing in the gallery.”

It seemed a natural next step to attend the Rhode Island School of Design when it came time for college, but the curriculum soon proved alien to her temperament. In 1969, the prevailing academic discourse “was over color field versus representational versus conceptual.” Speed already had her own way of looking at the world from years of museum going: “It didn’t matter to me whether something was abstract or representational,” she recalls. “Malevich looked the same to me as Piero della Francesca. Everything they were talking about in school had nothing to do with that. Within six months I realized I didn’t want to be there.”

But she gave it a second year, switching to courses in illustration. “My professors said, ‘You can do this on your own. Don’t bother coming to class.’” At semester’s end, she dropped out and took to the road with the man who would become her husband, Fran Christina, a drummer who played mostly with blues bands. “We traveled around the country for seven or eight years, doing pick-up jobs, farm labor. I trained horses, I waitressed. Because we were always moving, we often didn’t have places to stay, but I always had my pen and I could always draw.”

In 1978, the couple moved to Austin and established a more stationary home base. Christina was on the road much of the time, but by 1980 Speed could quit the part-time work—which at one point included painting a chuckwagon for a television series to make it look dirty—and concentrate on her art. She describes her subjects decades ago “as pretty much the same as what I’m pursuing now, but not as good.”

With her husband traveling so much, the artist would take what she describes as “mental health breaks,” making trips westward toward Marathon and Marfa, TX. “I loved Motel Sixes and would stay there,” she remembers. “Going west on Route 10 there’s this place where the geography changes, and all of a sudden you can see the horizon. Whatever little thing was making me crazy would float away when I could see the big sky and stars.”

After several trips to Marfa, Speed and Christina decided to move to the town Donald Judd, the high priest of Minimalism, made famous for its sprawling barracks-style galleries devoted to artists whose sensibilities could not be farther from Speed’s. And yet the circumstances that prompted their relocation and the buildings they ended up acquiring seem perfectly in synch with the improbable worlds the artist creates.

As Speed tells it, they “accidentally bought a little house in 2006.” They weren’t shopping for properties, but as they were stopped in front of a real-estate office, “talking about what a stupid idea” it was to move to Marfa, they noticed a man in the middle of the road, waving his cell phone to stop traffic from crushing a tarantula that was scuttling across the pavement. (Hairy male tarantulas, with a leg span of up to five inches, go on the move during mating season.) “Fran and I looked at each other and said, ‘Oh, my God, this is our town.’”

They acquired a small house behind the courthouse, and then later bought the former jail, which has become Speed’s studio. In the last three years, while renting out the first house, the couple have expanded to a complex of buildings, which will become part of a foundation supported by her “long-time core collectors.” For years, Speed showed with Gerald Peters Gallery in New York but now mostly represents herself, hanging shows in the studio and selling on Instagram to her collector base.

For all their storybook appeal and elusive iconography, Speed admits to being affected by current events, though these never become overt political statements. Cultural clashes, East vs. West, are a subtext of Samurai warriors reacting in a scene of the Crucifixion. A small boy fingers the pin on a grenade as priests enact a fierce dance in the background. And her female figures are almost invariably sturdy characters, both white and brown, not the delicate maidens of conventional fairy tales. Call it a form of feminism or gender-bending, but they are almost mannish, neither overtly sexy nor traditional visions of womanly beauty (even a borrowed image of a tender Madonna morphs into the head of a beady-eyed crow).

As for her working methods, now as earlier, the artist taps into a subconscious well of ideas and her practice blurs the boundaries between abstraction and realism. “Because my paintings are representational, people assume that I come up with an idea and then paint that,” she says. “But it’s usually that I’m painting an abstract composition, and then I put the flesh on the bones. When I start a painting, the head is just a circle. I don’t know whether it will be young or old, male or female. One thing simply leads to another.”

Ann Landi

Top: Good Friday (2015), gouache and collage, 29.5 by 37.5 inches

You can find more about Julie Speed at juliespeed.com and https://www.instagram.com/speedstudiomarfa/

Great article – I really enjoyed seeing Julie Speed’s work and reading her story. Glad to learn about other artists who are pursuing their own vision apart from the mainstream.