First off, let’s get the famous forebears out of the way. Yes, Jeannie Motherwell is the daughter of that Motherwell, Robert, one of the titans of mid-20th-century American art. And the stepdaughter of Helen Frankenthaler, no less famous in the annals of art history as the inventor of a staining technique that is often said to have spawned the Color Field movement. Together, they were the glamour couple of the New York art world in the 1950s and ‘60s, the Carole Lombard and Clark Gable of the newly minted American avant-garde.

In conversation, Jeannie Motherwell brings up the analogy herself: “It was like being the daughter of two famous movie stars, and you want to be an actress too. I often found it overwhelming. You can either walk with it and feel confident, or you can say, I need to figure out who I am. And that took a while to process.”

But, as Motherwell points out, she was not part of the Robert-Helen household full time as a child, and she and her younger sister, Lise, were raised during the school year by their mother in northern Virginia, with the exception of two years full time in New York when their mother was going through another divorce. Summers she spent with her father and Frankenthaler in Provincetown, MA, with occasional visits to New York. Nonetheless, it was an ambience that had to have an impact on an impressionable girl. “I can remember having play dates, and kids would come over and wonder, What is that stuff on the walls? Mostly they were my dad’s and Helen’s paintings, but they also had works by Ken Noland, Rothko, and sculptures by David Smith and Matisse.”

Frankenthaler and Robert Motherwell separated just before Jeannie went off to Bard College in 1970. That year her father took her with him on a trip to France and St. Gallen, Switzerland, to do some printmaking, and to Germany, where he picked up a Mercedes convertible, at that time not available in the States.

“After we picked up the car, we drove all through the winding roads of the South of France with the top open to the summer air,” she recalls. “We bonded on that trip. It was the first time I was having adult conversations with my father, at a time when I was developing my own interest in art and had found the school where I was going to major in painting.”

At Bard, she says, “it all started to click.” The faculty were a sophisticated group who showed in SoHo and had already made names for themselves. In her junior year, Motherwell took a loft in SoHo, too, and commuted back and forth between college and Bard. “I was really in the thick of it,” she recalls. “But I was also very intimidated. I felt I needed to perform at the level of Helen and Dad.”

After college, Motherwell says, it was time to determine if she was “going to paint for the rest of her life or not.” She decided to spend a couple of winters in Provincetown, alone in a studio, to test her mettle. Though she was intimately familiar with the area, it was always as a member of the summer art crowd. She’d never really gotten to know the locals well, but that first winter she became friends with the fishermen and their wives. One of them invited her for a drink at 10.30 in the morning and told of plans to go out for a few days because the scallops were running “in a big way.” Motherwell wouldn’t accept his offer for a drink not only because of the time of day, but because she was on her way to riding the bike trails in the dunes of Provincetown. He said, “’Gee, I can’t even give away my money’ as he pulled out a wad of hundred-dollar bills.” The boat was lost off Wellfleet because it was so filled with the day’s catch that it sank. “Before finding his body, they found his wallet, stuffed full of hundred-dollar bills.” Her works from the winter referenced the boat lost at sea. “It was my own elegy,” she says. “The town came together as a community and I was compelled to make a stack of paintings about the tragedy.”

In 1981, Motherwell married her first husband and a year later had a daughter, Rebecca. For about a decade, she stopped painting, and when her father became sick, she moved to Greenwich, CT, nearer to his studio and home so that he might have some time to get to know his only grandchild. In 1991 her dad died, and a year later she and her husband separated. “Here I was stuck in this predominantly white upscale suburb, but my daughter was in school and I waited until she finished the ninth grade to hightail it out of there to Boston.” Her sister was living in Cambridge, with a house in Provincetown, and Motherwell herself had many friends in the area.

Within a couple of years, she was working in arts administration at Boston University and “getting back into art.” She also met her second husband, Jim Banks, a former college friend, at a time when he too was working on resurrecting his career as an artist. “Jim would come to visit me and would start painting, and I would take some pieces of paper and turn them into postcards to send to him or to friends. He said, ‘Why don’t you just have fun?’—a new concept from what I had grown up with. That’s when I started making small intimate collages, they got bigger, I began exhibiting, people started buying, and then I was off and running.”

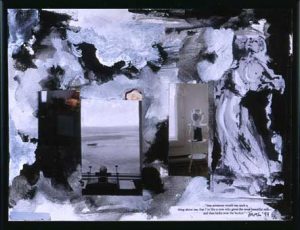

Motherwell is now painting full time and says it’s only within the last five years that her approach has truly evolved into something recognizably her own. If once the sea and its great churning mysteries provided an inspiration, she now looks to pictures of outer space, specifically to images taken by the Hubble telescope. She works in acrylic on clayboard, on canvas with an especially absorbent ground, and on Yupo paper, and is equally comfortable with a dramatic scale (up to six feet long) and the more intimate format of paintings on paper.

The influences of Frankenthaler and her father are apparent, but they are also values embraced by much of that ground-breaking group, still ongoing among painters today: spontaneity, intense color, and a basic trust in the possibilities of chance. If anything, Motherwell has surpassed her elders in cultivating a lush and opulent vision that builds on the lyrical impulses of a previous generation, call it expressionism without angst. Her works, she says in her artist’s statement, “often carry me in directions I cannot anticipate. I like to think of my paintings as an ‘event’ or an ‘occurrence’; that is, an action that emerges in the here and now—where the subject matter symbolizes the images and mysteries of creation.’

Visitors to Provincetown this summer can judge for themselves, as Motherwell has a show at AMP Gallery from July 27 through August 8. Helen Frankenthaler’s work, curated by Lise Motherwell and Elizabeth Smith, will be at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum through September 2.

Ann Landi

Top: Limitless (2016), acrylic on clayboard, 24 by 72 by 2 inches

Tremendous work! Thank you for continuing to bring so many artists on each other’s radar!

a very nice read. Navigating life and becoming an artist with famous parents with aplomb. The work is lush, the painting “Pompeii” is terrific.