Like many kids, Jackie Skrzynski (pronounced skrin-ski) was an ardent draftswoman from a very young age. “The idea of moving lines around the page, and then having them turn into something recognizable, was just magic to me,” she says. These days, as her work has taken a turn toward abstraction, the drive to make things that have real-world counterparts may have abated, but drawing has been her preferred medium at least since she was a graduate student the State University of New York at Albany.

Even earlier, as an undergrad in North Carolina, Skrzynski discovered some important antecedents for an innately dramatic sensibility when she spent a junior year abroad in Spain and was smart enough not to let “classes get in the way of my learning experience,” as she puts it. There was “over-the-top Baroque artwork everywhere,” she recalls, and she was in particular attracted to Spanish artists like Goya, Ribera, and Zurbarán—all masters with a certain dark and occasionally grotesque sensibility. “I preferred an unsettling aesthetic,” she says. “Seeing those artists reinforced that identity within me.” (The artist notes that her grandmother came from Poland, and the art steeped in Catholicism in both Spain and Poland tends to contain a lot of elements of high drama.)

After graduation, Skrzynksi scraped together a living—waiting tables and working in a real estate office–while making art in the Catskill Mountains in New York. Eventually she gravitated to Albany and was accepted into the MFA program, where she studied with artists Ken Johnson (who would later become a New York Times critic) and Mark Greenwold, a painter whose figures in fraught domestic situations have been described as “executed with pathologically laborious detail” (but one can see how Skrzynski might have learned a thing or two).

“That time in Albany had me completely submerged in art making,” she recalls. “There’s a point in grad school where you begin to figure out what you’re doing, when ideas are starting to form.” She remembers in particular a time when Johnson came into her studio for a visit. “I had drawings of figures in landscapes, work that was about 20 by 30 inches. And he said, ‘What if you made this four times as big?’ He was saying the right thing at the right time. It was like my head was exploding.”

But Skrzynski adds that she did most of her studies with Thom O’Connor, a minimalist print maker she describes as the formalist counterweight to Greenwold and Johnson. “Because of him, I want to make drawings that work from across the room and also from six inches away.”

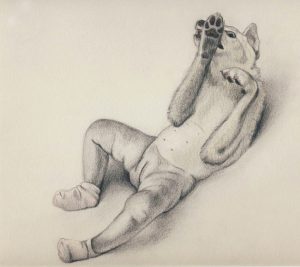

Once out of grad school, she started teaching at Ramapo College in northern New Jersey (not far from where she lives now, in New York’s Hudson Valley) and making work that was “loosely autobiographical,” but also infused with a love of metaphor and personal mythology. A group of drawings called “Hybrids,” from the time she started a family, combines the human and animal in ways that are startling, scary, and often tender: a creature that is half-dog, half-baby nervously shows its paws or in Self-Portrait as Sow, the artist nurses a litter of piglets from multiple breasts.

“I was having anxieties about becoming a mother, and many of these drawings were made while I was pregnant,” she recalls. “The studio became a safe place to go to the dark side.” Even though traditional mythology is often about fantastical creatures like griffins and dragons, she “started looking at our dogs and other domestic animals and thinking how they could be mythologized.”

After she became a mother, Skrzynski’s focus shifted to her kids, “about the experience of being a parent and the ability to provide protection.” Again, the drawings can encompass both the grotesque and the affectionate: a little girl naps with what looks like road kill or a small boy brandishes a gleaming sword (and it’s hard to tell if it’s a toy or the real thing).

In recent years, she’s turned her attention to the world of animals, and the brutal ways their lives end as road kill or at the hands of hunters. The works are matter-of-fact and nonjudgmental, but nonetheless chilling in their subject matter (a wolf with its paw caught in a steel trap, a huge elephant brought down by a tiny smiling shooter). As photographs, these would be heartbreaking enough; as drawings they are somehow even more poignant.

In addition to teaching and her studio practice, the artist put together a year-long project called “Silent Walks on the Half-Moon” (2009-2010). Participants “met once a month at the trail head of Storm King Mountain at 6 p.m. on the waxing half-moon,” as described on Skzrynski’s website. “After the walk, which generally lasted about 30 minutes, they shared some refreshment and wrote their impressions on index cards.” Somewhat inspired by Andy Goldsworthy’s adventures in nature, the walks were about moving through landscape as an experience, rather than simply looking at a landscape in a gallery.

Skrzynski has also worked as an occasional curator, paying special attention “to the conceptual and aesthetic flow” of artists in the Hudson Valley. “Every two years or so I get a grant and curate a show,” she says. “It’s a wonderful time to be on the other side of the table, the person who visits artists’ studios and thinks about how a show might come together. I don’t like to include my own work, because I don’t want to deal with the politics of that. As a curator, my goal is to make an artist look as good possible.”

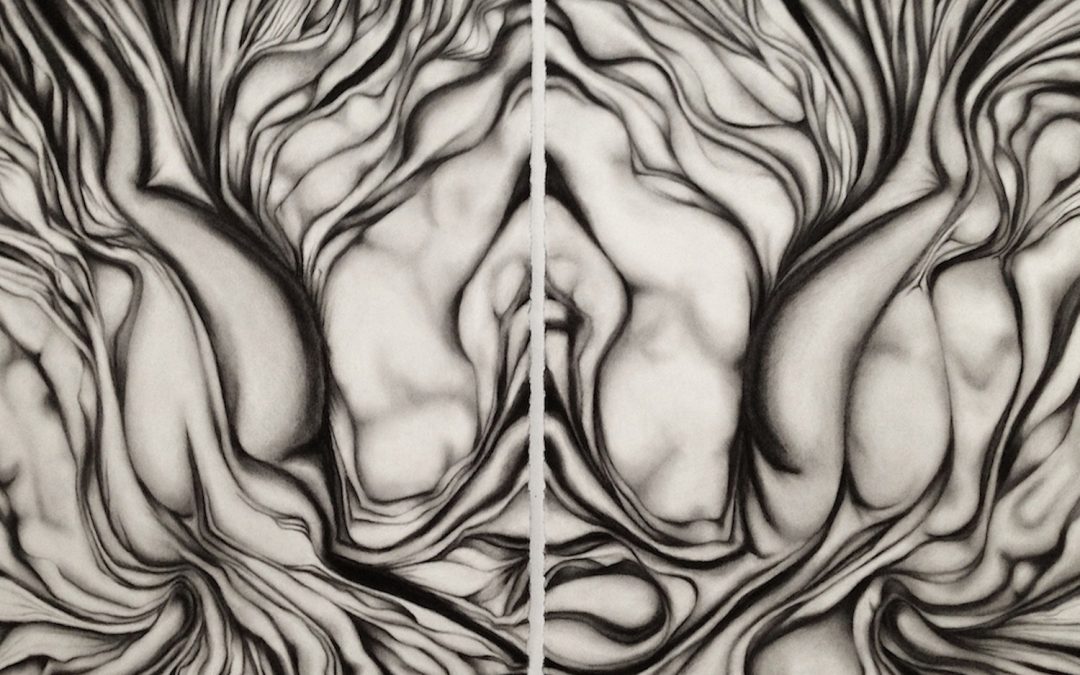

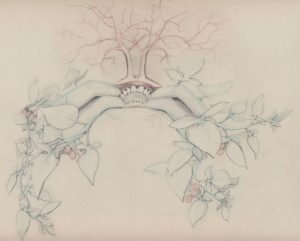

But in the end, it is drawing that remains the heart and soul of all her endeavors. The most recent works venture into a tangle of the biological and the natural worlds, cramming what look like entrails and other bodily oddments into claustrophobic spaces. “I’m transitioning from being a parent to what comes next—feeling the changes in the way my face looks, the way my body reacts. I might make a drawing of the corner of my eye and combine that with parts of a gnarled tree. The new drawings are based on anatomy and nerve cells, specific points of reference.” (Recent works are currently on view at the Seligmann Center of the Orange County Citizens Foundation in Sugar Loaf, NY, through April 26.)

“There’s something about drawing,” she says. “You’re touching the surface of the paper—it’s a very tactile, sensual kind of experience. I’ve never gotten bored with it.”

Ann Landi

Top: Jackie Skrzynski, Stretch (2016), charcoal on paper, diptych, 45 by 30 inches