Ilona Pachler

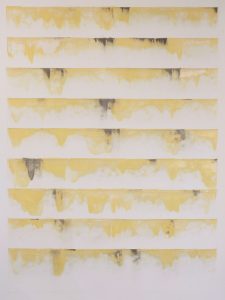

An early tapestry installed in a private home: Energy (1986, cotton warp hand-dyed wool, 5 by 8.5 feet

Ilona Pachler’s new show at 5. Gallery in Santa Fe, NM, is titled “Zeitbrechung,” a German word meaning “time refraction.” It’s a motley assortment of artworks: 34 crudely modeled clay boats, most on plinths of wood or bricks, cruise the floors of the gallery. A quartet of evocatively scratched surfaces called “Refraction Mirrors,” which look as though they’ve been charred by fire, line the walls, as do screen prints of a marble goddess and an elegant crystal chandelier, and small blocky shapes in clay. From the ceiling hangs a cast-glass pendant, suggesting a window ornament from an old-fashioned pharmacy or a weightless perfume bottle.

It’s a lot to absorb and interpret, but conversations with the artist, a lively woman with precisely sheared dark hair, help illuminate the underpinnings of the show. “It’s called ‘Time Refraction’—not ‘reflection’—because it’s a breaking down between two different historical periods, the Austrian Baroque and ancient Greece, represented in the boats,” she explains. The 34 clay vessels are an allusion to the Catalogue of Ships in the Iliad, Homer’s saga of the ten-year siege of Troy, and the title, In her command sailed 34 black hollow vessels, feminizes a line from the text. The screen prints come from photographs she took in the imperial palace in Vienna, a city in which the artist has spent a fair amount of time. And the mirrors, seen from their reverse sides, reveal the copper linings that were once common in the manufacture of reflective surfaces.

We do not delve too deeply into the glass pendant, called Plumb Bob, or the clay relics. But why the Iliad? I ask. “I was thinking about current issues in our life, the heightened threat of wars—in the Middle East, and the possibility of nuclear destruction—and I wanted to read something political,” she says. Max Baseman, director and owner of the gallery, suggested the Iliad, which they are now reading together. “I started working with mirrors from the back, so that they don’t reflect, they refract.” The entire installation bounces around different eras and cultures, from the very primitive clay “relics” on the walls and floor to the high culture of the Austrian Baroque.

And perhaps there is a measure of autobiography too, as Pachler herself has traveled across cultures in her work and life. She was born in Linz, Austria, a town of Baroque buildings on the Danube, about midway between Vienna and Salzburg. When she was three, the family moved to India (her father supervised steel mills), and she became the only white child in a Hindustani kindergarten. She returned to Austria when she was seven and soon became interested in theater, language, and art. An uncle who was an artist taught her to draw. After that, she says, “I never had to worry about being bored.”

Her professional training was as a commercial graphics artist, but she also studied weaving, painting, and drawing at the Academy of Fine Arts, supporting herself as a weaver for several years. On vacation in New York, she met her future husband, and eventually relocated to the city. The couple lived in the famed Chelsea Hotel, which in the 1980s was still a hotbed of bohemian life. Pachler worked at odd jobs and launched herself as an artist, then concentrating on weaving, a skill that landed her a job with the Metropolitan Museum’s conservation department. At the Met she was assigned to a project to restore fabrics from the age of Louis IV. The textile studios were in the basement, and she lasted little more than a year, noting wryly, “I’m not a big corporate person, and it was difficult for me to work underground all day long.

Caput Mortuum and Temptress (both 2016), from the show “Zeitbrechung,” screenprints behind plexiglass, each 27 by 43 inches

Pachler began to enjoy some success in her career as an artist, working with consultants and making landscape-inspired tapestries for IBM and a private firm in the Citicorp building. For seven years she also assisted with projects in a private gallery that specialized in Pre-Columbian textiles. She stayed in the city for two years after her marriage broke up, and then on a vacation to Santa Fe, she fell in love with the New Mexico landscape and made plans to move.

“The last piece I wove in New York was a kind of banner with the words ‘What If?’ worked into the design,” she remembers. “This was my good-bye to weaving and to New York.” It seemed both ironic and appropriate that it was bought by the Austrian Ministry of Culture.

After picking up stakes for Santa Fe in the early ‘90s, she experimented with different materials. “I didn’t want to use traditional techniques,” she says. “I worked with acid and bleach. I tore and I cut. I did everything I could do to transform the material.”

Eventually she started photographing light and shadow and experimenting with ways to print the images. During a residency in Austria in 2011, she remembers taking long walks with her camera up and down the Danube. “This was the first time I was back in the place where I was born, and that’s how I came to start thinking about memory.” Another residency, at the villa Wittgenstein in Gmunden, Upper Austria. led to investigations into collective memory—what are the things we all remember?—and have informed her works of the last few years, leading to what she calls on herwebsite “a new visual syntax.”

In assembling a collection of artworks in various mediums with varying reference points, Pachler—whether she is aware of this or not—fits in with a trend among contemporary artists: the early installations of Carol Bove, for example, and the ongoing projects of Rachel Harrison, as well as the lavishly praised shows of Turner prizewinner Helen Marten. Yet illuminated (or not) by a bit of back story, “Zeitbrechung,” with its primitive restless ships and images of Baroque splendor, resonates in surprising ways, becoming not unlike the fragmentary nature of memory itself. (The show is on view at 5. Gallery till June 24.)

Ann Landi

Top: An installation shot from “Zeintbrechung” at 5. Gallery in Santa Fe, NM