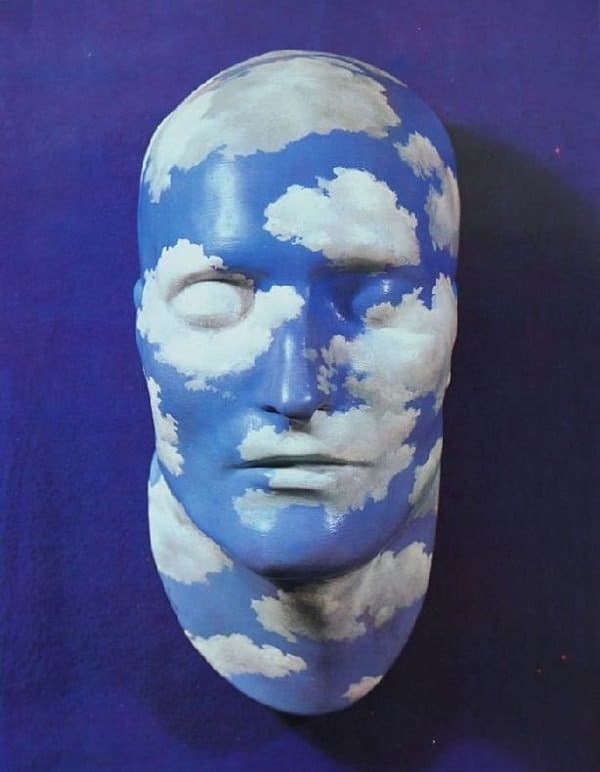

Art director George Lois’s collection included one of René Magritte’s 1937 painted plaster “death masks” of Napoleon

A few cautionary tales

In the years between acquiring a master’s degree in art history—and burning out on the prospect of becoming an art historian—I did a number of reasonably adult things. I got married. I held down a series of editorial jobs with magazines that ranged from the ridiculous to the ambitious. I freelanced for publications like GQ, Travel & Leisure, and an adventurous but short-lived magazine called Manhattan, inc.

At a certain point, as my ex-husband’s income started to rise significantly above mine, I decided we ought to embellish our status as card-carrying Yuppies and acquire some art. I had not yet begun writing about art in any serious way (that would happen later, when I joined the staff at ARTnews in the mid-90s) but I figured an art-history degree might qualify me for some level of expertise.

Not really. I didn’t have a clue about the gallery system, I wasn’t particularly up to speed with contemporary art, and essentially I began buying things to complement the furnishings of a house in Massachusetts. I found a nice oil painting in an airport, vaguely reminiscent of Rauschenberg, And bought that from the artist. We spotted an irresistible portrait of an androgynous youth by an obscure 19th-century genre painter in a gift shop (!) in Boca Raton, and snapped up that one too. I found a couple of stately William Hamilton prints (he who was abandoned by Lady Emma for the swaggering one-armed Admiral Horatio Nelson), which looked great above a leather couch. (Yes, dear readers, much to my shame, I did buy art to go with the sofa.) And there was a magnificent Audubon print of some bird whose name I’ve long forgotten, which went in a divorce agreement to the second Mrs. Landi.

This was all rather nice stuff. I still have the Hamiltons and the Thomas Moynan portrait, but all else has scattered to the winds in the wake of moving, splitting up, and other reversals of fortune.

Adman Lester Wunderman acquired a first-class collection of Dogon sculpture, like this one by the Master of the Slanted Eyes

It wasn’t till I got to ARTnews and starting writing and editing stories about collectors that I realized how the real pros operate. The high rollers, who don’t much interest me, generally use art advisers, attend auctions, and have an inside track at the blue-chip galleries, but there is an intriguing stratum of passionate “mid-level” collectors who go about the acquisition of art with curiosity, zeal, hard looking, and focus. Like Herb and Dorothy Vogel, of course, the Munchkins of the art world, who acquired a first-class collection of Minimal art early in the game, on a librarian and postal worker’s salary. Or Wynn Kramarsky, whose collection of 4,000 works encompassed what he called both “newbies” and “namies” and expanded the concept of what we think of as a drawing. Or adman Lester Wunderman, whose life was changed by a visit with the Dogon tribe in Mali, and who subsequently acquired a magnificent collection of West African sculpture, good enough to deserve an exhibition at the Met. And George Lois, the legendary art director of Esquire, whose acquisitions ranged from Cycladic idols to Magritte’s plaster death mask of Napoleon, and who often got up in the middle of the night to spend time with his art.

One of my favorites was a collector I never profiled, the grandmother of a good friend, who had a lovely and spacious apartment overlooking Central Park. She had married three times, moving ever upward through matrimony, and acquired some excellent Impressionist paintings, along with works by Vuillard and Eli Nadelman. It was not the sort of collection that would interest either the museums or the art press, but it was lovingly assembled, and as an old, old lady she liked to tool around the premises in her wheelchair, spending time with each of the works. That’s a real art lover.

One couple I wrote about for ARTnews truly perplexed me. They were at the fortunate point in their lives where the mortgage was paid off, the kids were in private schools, they’d bought the summer house, and had enough cars and electronic gizmos to accommodate the family. It was time to buy art. Somehow they had stumbled upon Ann Freedman, director of Knoedler, which was then, I believe, handling the David Smith estate.

Freedman was in the process of showing them some Smith spray paintings from the “Cubi” series when your intrepid reporter entered the picture. The dealer was very good at explaining the artist’s processes and his importance to art history, and as I recall the couple bought two or three of the works from the gallery. They were also intrigued by some Helen Frankenthaler woodcuts. Later I asked if they had been to other galleries, if they were out looking for their own edification. “Oh, no,” answered the husband, “We trust Ann completely.” (A curious statement, in light of Freedman’s subsequent trial for fobbing off forgeries when at Knoedler.)

As you will read this week, there’s nothing wrong with having a dealer introduce you to her stable of artists, to have her guide you by the hand and help eliminate the understandable trepidation novices experience when approaching galleries. That’s what Walt and Louise Rosett did when they first began to collect art for their home in New Mexico. But they went off on their own after a couple of years, visited other galleries and art fairs and studios, and honed their eye to the point where they could assemble a collection with both coherence and individuality.

And those are the kinds of collectors—not rich, not Gagosian shoppers, but passionate and self-taught—I hope to be bringing your way in future weeks and months. Along with sage advice from dealers and curators on the best ways to build a collection.

Top: The Cone sisters from Baltimore, who assembled one of the finest collections of French modern art, with Gertrude Stein, center.

I’m so glad that the internet allows free info like this!

Well, you can always make a donation if you’re feeling generous!