For many years now, Grace DeGennaro has been looking for ways to combine the sacred and the secular through “simple” geometry that turns out not to be quite that simple once you become seduced by the mesmerizing patterns and understated colors. “My work is the kind of work you need to look at for a long time, as lengthy a time as possible,” she says. “You can’t see a lot of the subtleties online. The geometric shapes are far from perfect, and even though there’s a pattern and a grid, they’re humanized by the marks of the hand.”

Born and raised in Huntington, NY, DeGennaro did not become interested in art until she was at Skidmore College in upstate New York, where she started off as an English major. But the school had a great visual arts department and “within my first year, I was in the love with the materials, even the smell of the materials,” she recalls. Most of her classes were traditional tutorials in drawing and painting, including a course with a professor who had once been a student of Josef Albers.

For a couple of years after college, DeGennaro worked in a non-profit human-services agency in Boston. “The job was in a residence for women with developmental disabilities, teaching life skills and helping to manage the household,” she remembers. “The hours were three to eleven, and I painted during the day in the living room of my apartment.” She then got a job doing illustrations for the publications department of an engineering firm. “I worked at a drafting board, making drawings using stencils, rulers, and rapidograph pens,” she says. “There were tight deadlines, and if you made a mistake you had to start all over again. At the time I hated it, but now I realize this was my first real introduction to geometry.”

In the evenings, she was taking classes at the Museum School in Boston, and in 1984 applied to graduate school in New York. Columbia University’s MFA program was “where it all turned around for me,” she remembers. “I started thinking seriously about content and realized I wanted to be a more abstract artist. I was keeping a dream journal and calling on images from literature and poetry, images that were more from imagination than observation.” The late Jane Wilson, a prominent landscape painter whose works hovered close to total abstraction, was DeGennaro’s adviser and the one who first identified the passage of time as a theme in her work. Two other women artists who impressed her deeply in the 1980s were Susan Rothenberg, an artist known for her agitated imagery within an abstract field, and Jennifer Bartlett, who brings a humanized dimension to austerities of Minimalism.

At the time she graduated from Columbia, in 1986, the artist discovered she was pregnant with her first child. Two years later a second son followed. “Things slowed down a bit,” she says with serene understatement. The family moved to Hastings, NY, where her husband, Jerry King, commuted to his position as a software designer in the city and she did some teaching and layouts for a local newspaper. She also kept a studio in Yonkers, where she could work at night.

A few years later, King was offered a job in Maine with a big insurance company, and the relocation proved too hard to turn down. “The boys were two and three, and I knew we could live near the water,” she says. The family has lived in Yarmouth, ME, about ten minutes north of Portland, ever since. At first, with two small kids and no community of friends or colleagues, DeGennaro found it difficult to acclimate; she’d also never lived any place as rural as Maine. “It took a while to get going again,” she recalls. “I don’t think my work was that good at first, but you become even more disciplined when you have children.” Maine now, she says, has a “terrific community for artists,” including a new building for the Center for Maine Contemporary Art in Rockland.

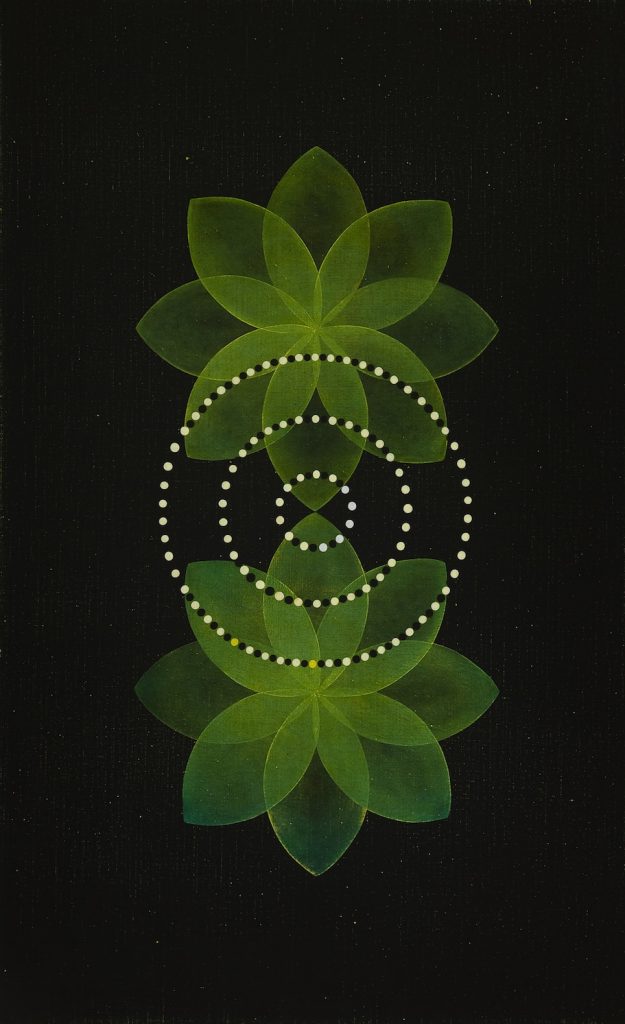

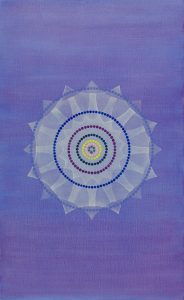

DeGennaro did not begin to develop her current “mature” vocabulary until the mid-1990s, but she credits “Primitivism in 20th-century Art,” a controversial exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1984, with awakening a fascination with the repetitive mark making of African art. “I wanted to make work that had meaning, that wasn’t just about other art, and that exhibition was a turning point for me. I started looking at Tantric art, sacred drawings, and Native American art. Sacred geometry became something I studied for many years. But how everything came together for me is a bit hard to explain.” (One day, she says, she was “just fooling around with stencils” in her studio, making overlapping circles that were geometric but still felt organic.)

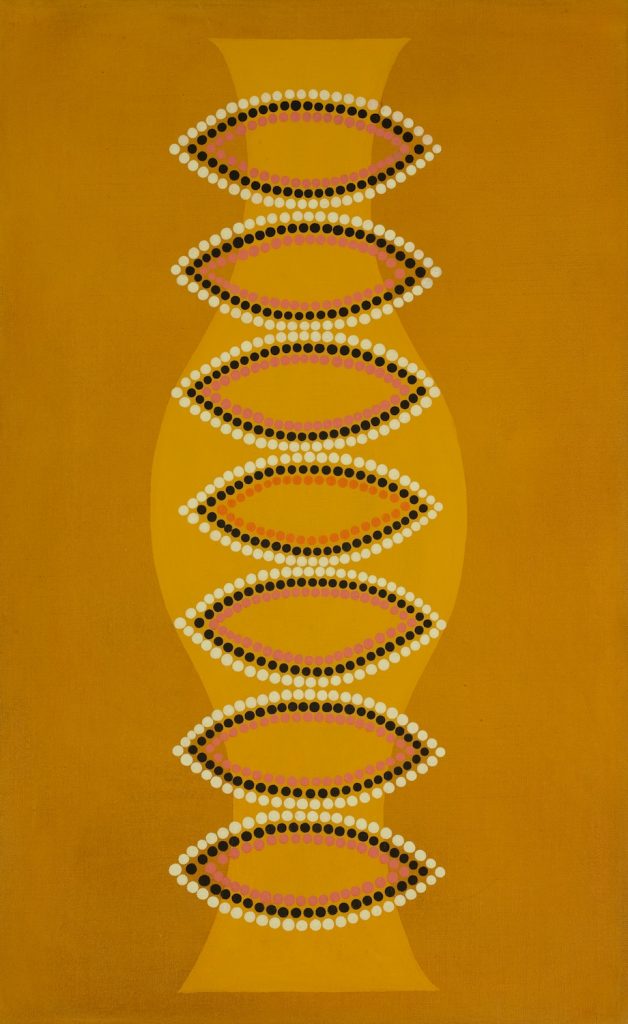

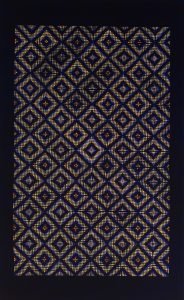

DeGennaro’s paintings and works on paper all have an almost hypnotic quality, though the content and colors vary hugely. “The accretion of dots and beads of color into patterns has been prominent in my work for the last ten years,” she explains. Her colors come straight from the tube, and she relies on the Albers color theory of changing the ground to change the impact of the work.

“Working here in Maine, where life is quieter and simpler, has certainly affected my paintings,” she notes. “I’ve limited my vocabulary, but there are still so many iterations of what I want to make.”

Ann Landi

Top: Creation (installation, 2017), oil on linen, each 26 by 16 inches.