Gelah Penn’s installations bristle with spiky energy, hugging the walls or colonizing corners, suggesting habitats created by insects with a taste for sci-fi, or abstract line drawings catapulted from two dimensions into three. The works are made from cheap and ordinary stuff—synthetic materials like netting, fishing line, garbage bags, and plastic tubing—but in Penn’s hands these assume a busy, restless life, even as their titles hint at something a little more sinister.

Although she knew from the time she was in junior high that she was serious about art and has made both paintings and sculptures during the course of her career, the artist says her central interest has always been in “expanding the language of drawing.”

Penn grew up outside Pittsburgh, PA, and later moved to Washington, DC, when she was 13. The daughter of Holocaust survivors—her mother was a Hebrew-school teacher, her father sold furniture—she claims that legacy does not really inform her work. “My parents’ history isn’t my history,” she says. “But it’s the disquieting and sometimes chaotic background noise for much of how I think and approach things. It has probably fueled my profound interest in movies, and particularly the uneasy territory of film noir, as well as contemporary psychological mysteries.”

After a year at Brandeis University, outside Boston, Penn dropped out and returned to Washington to work for the American Film Institute for a year, cataloguing films from the 1920s. “I’ve always been a big movie buff, so this was perfect,” she says. “I had the opportunity to watch a lot of terrific old silent films.” (Titles of her installations years later—The Reckless Moment, Night Moves, and Shadow of a Doubt—reference that ongoing fascination.)

She picked up her art education with design and drawing classes at the University of Maryland, and then gravitated to the San Francisco Art Institute to finish a B.F.A. There she studied with Kathan Brown, founder of Crown Point Press, among other “engaged, intense Bay Area artists.” After taking a year to explore Italy, Penn settled in New York with “two other artists living and working in the same space. It was tough. It was not a big loft, but we managed and we’re still good friends.”

The Naked City (2011), mixed media, dimensions variable. Marie Walsh Sharpe Foundation, Brooklyn, NY

To help support herself, she worked part time as an administrative assistant to the programs director of Dia Art Foundation, then in its infancy in Tribeca and a haven for both Earth and Minimalist artists. “I was privileged to get firsthand exposure to the work and processes of Fred Sandback, James Turrell, John Chamberlain, and other significant contemporary artists,” Penn recalls. “It was a seminal experience that initiated both a close examination of ideas and an exploration of materials in my own work.”

Her work, at the time, was abstract painting, primarily diptychs and triptychs. “At a certain point, I found myself putting stuff on them, like synthetic hair and tubing,” she says. “They were becoming more and more sculptural.

“There’s a lot of Eva Hesse in those early pieces,” she continues. “She was a major influence, but I began to realize that hair is a very potent fetishistic metaphor, and that’s not what I was about.” So monofilament and plastic mesh entered her vocabulary. “I also found that I’m really much more of a modeler than a builder, so I started using found objects like bird cages—things I could weave these linear materials in and out of. The final big shift was to eliminate the armature completely and work on the wall. And that’s where I’ve stayed.”

Penn begins the installation process with a site visit and/or photos, followed by “rudimentary, ruminative sketches.” Another writer has noted that she is “especially drawn to such ‘architectural curve balls’ as columns, arches, and ductwork, responding to spatial challenges with line, shape, and sometimes color as she creates…installations that climb up walls, wrap around corners, and tumble down from ceilings.”

The day of my visit to her Brooklyn studio, which she shares with her artist-writer husband, Stephen Maine, Penn is working on both drawings and a corner piece made from fishing line, mosquito netting, colored staples, and bits of black plastic garbage bags—the whole apparatus miraculously and delicately held together by T-pins, used by tailors to make patterns. “I like them because I’m constantly moving elements around when I’m installing.”

Where the Sidewalk Ends (2012), mixed media, dimensions variable. National Academy Museum, New York, NY.

The “drawings” are about as far as you can get from traditional notions of that medium and more like sculptural collages constructed from pours of acrylic paint, eyelets, torn garbage bags, staples, Mylar, and lenticular plastic. “I’m interested in that contrast between quotidian materials and the glitzy ones like optical plastic,” she says.

Next month Penn will pull together a solo exhibition that includes a massive installation and drawings, opening April 1 and on view through May 6, at the Amelie A. Wallace Gallery at the State University of New York in Old Westbury. “The galleries are on three levels, three very different spaces that flow into one another via ramps,” she explains. “I have an idea of where I want concentrations of ‘marks’ and will work up certain passages in my studio in preparation, but most of the decision-making is done on site. It’s a bit like taking your studio practice out into the world.”

Ann Landi

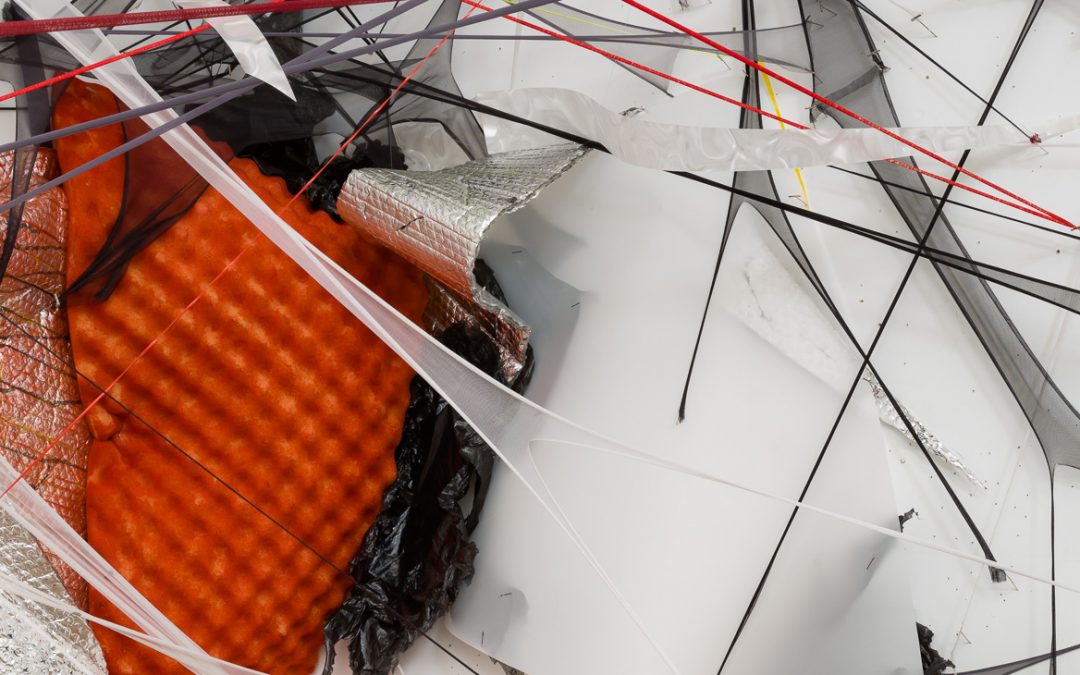

Top: Detail of The Big Red One, Two (2017), mixed media

I LOVE this work! Thanks Ann!

Congratulations Gelah Penn and thank you Ann for introducing such good work I love Gelah’s abilities with space!

Gelah’s work is very cool and interesting! It’s great to learn about “new to me” artists. Thanks Ann.

Fabulous work: seeing the details is so clarifying.

I’m a fan of Gelah’s work and your article provided further insight into her processes and musings, thank you.

Many thanks for everyone’s generous comments, and to Ann Landi, of course, for this wonderful piece.