When is a prank a work of art? And when is it just a one-liner?

During a panel on the “Art of Pranks” at a convention of the College Art Association a few years back, a participant identified as Clark Stoeckley, “Artivist,” maintained a totally impassive, even bored, demeanor, as a handful of his scholarly colleagues delivered papers on Dada, Fluxus, and other notorious high jinks past and present. Stoeckley stood out from the others for his cop’s uniform, and when he got up to speak on the topic of “New York City Pranksters,” identified himself as a member of the NYPD Vandal Squad Task Force. A former undercover detective in the East Village, he became a “street-art archivist,” he claimed, and was promoted to the rank of lieutenant for his insider knowledge of graffiti crews and activist groups.

Stoeckley’s 20-minute talk covered the gambits of street artists, from Banksy and Shephard Fairey to the Guerilla Girls and the group known as Mat Benote (Make Art that Benefits Everyone Not Only the Elite). Though he seemed a little awkward and stiff in front of an audience, he punctuated his stories with wry observations that drew appreciative laughter. “This is the stuff that really brightens our day,” he remarked, “and in many cases teaches cops like me a lesson about the Constitution.”

The presentation was so entertaining and unexpected (New York’s finest tagging after pesky artists? who knew?) that this reporter wrote it up as an “Art Talk” item for a spring issue of ARTnews. Only to be told a short time later by sharp-eyed staffers that “Lieutenant” Stoeckley had no affiliation whatsoever with the NYPD and was himself an artist with a long history of performance-based work. Gulp. The whole charade felt somewhat like getting rooked into buying a line of cosmetics from Rrose Sélavy.

But even after this revelation and rereading the papers delivered at the CAA, one was still left wondering, What exactly is an art prank? And why has the past century, in particular, been riddled with jokes, hoaxes, forged identities, subversive graffiti, mass and solo performances with an aim to shock or annoy, and a whole roster of shenanigans that some would be loath to qualify as art at all.

In his introductory remarks as chair, Beauvais Lyons, a professor of art at the University of Tennessee and author of the “Hokes Archives” (the name gives a clue to his endeavors), power-pointed a slew of activities under the rubric of pranks. These included Hugo Ball at the Cabaret Voltaire in 1916; Duchamp’s Fountain and LHOOQ; George Maciunas’ Fluxus street theater; works by Manzoni, Kline, Beuys, Warhol, and Hirst; Andrea Fraser’s impersonation of a museum curator; the Reverend Billy’s Church of Stop Shopping; and the “No Pants” subway riders, who showed up one Sunday on New York’s transit system scantily clad from the waist down. As part of his presentation, Lyons made a pitch for academics and critics to consider the possibility of “pranks theory” as a way of investigating and putting the official seal of approval on art history’s great jokesters. “I’m hoping people will reconsider the history of Modernism through prank theory,” Lyons remarked later.

But are all these truly pranks or put-ons? Wasn’t Hirst deadly serious when he floated that shark in a tank of formaldehyde? As was Warhol, when he presented his Brillo boxes and soup cans? Does the Reverend Billy qualify as an artist? Were Joseph Beuys’s “social sculptures” intended as pranks? And how about tomfoolery from earlier eras? Was Michelangelo playing tricks when he rubbed dirt into one of his sculptures and sold it as an antique Cupid (or was he just strapped for cash)? Is trompe l’oeil a joke? What about most forms of urban graffiti?

When one surveys this vast and unwieldy terrain, jokes and pranks in art (and I use the terms interchangeably) turn out to be as richly varied and diversely resonant as their distantly analogous verbal and written equivalents, which might include puns, shaggy dog stories, bon mots, satire, doggerel, and funny lyrics. But there is a world of difference between a knock-knock joke and Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal,” as there is between most of Banksy’s street art and Duchamp’s upended urinal. The one is usually good for an amused and appreciative double take; the latter asks us to think hard about how we look at art and the way it’s presented.

To some, Fountain is not a joke or a prank at all. Duchamp’s porcelain urinal, signed R. Mutt and submitted in 1917 to the Society of Independent Artists (which said it would exhibit anything accompanied by an application and a five-dollar fee), “had a higher purpose than whatever a joke is,” claims the art historian and dealer Francis Nauman. “A joke usually has that one quick response, for the laugh, and not much more. If it was for that purpose, then it failed miserably because it influenced generations of artists after it.” The real jokesters, to Nauman’s way of thinking, were those who showed a painting made with a donkey’s tail, under the name Joachim-Raphael Boronali, at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris in 1910. Or the Society of American Fakirs at the Art Students League, where between 1891 and 1906 students annually produced works parodying artists like John Singer Sargent and Thomas Eakins. Neither of these pranks, obviously, had any serious repercussions for the future course of art because we haven’t heard much about them since.

But Duchamp’s art reverberated down through the decades, in myriad ways, and one of his most powerful pranks was the invention of the femme fatale alter ego known as Rrose Selavy (“eros, c’est la vie”), who emerged in photos taken by Man Ray in 1921 and spawned generations of gender-bending antics. Think of the late Hannah Wilke, posing provocatively in men’s clothing, or the British performance artist Genesis P. Orridge, who, together with his wife, went through a quarter-million dollars’ worth of plastic surgery to turn themselves into matching blonde bombshells. They were so “into” each other they wanted to be each other. Which, of course, raises the question of when the prank stops and the pathology kicks in.

It might be said that all artists go through makeovers when they aspire to a certain level of notoriety, whether it’s Andy Warhol in his fright wig or Julian Schnabel in his pajamas. But perhaps none went to greater lengths than Joseph Beuys, who claimed to have been rescued from a plane crash by nomadic Tartar tribesmen in the Crimea during World War I. The artist later asserted that these Samaritans wrapped his body in fur and animal fat to nurse him back to health, and those materials became integral to his artistic process. (Eyewitnesses at the time say Beuys was rescued by German commandos; there was nary a Tartar in sight.) But this kind of self-invention goes back centuries: Michelangelo boasted that he “sucked in the craft of hammer and chisel” with the milk of his wet-nurse, the wife of a stonecutter, and Vasari made all kinds of lavish claims for the Renaissance artists he immortalized. Garnishing one’s biography seems often to be part and parcel of building a persona, but it is not necessarily intended as a put-on.

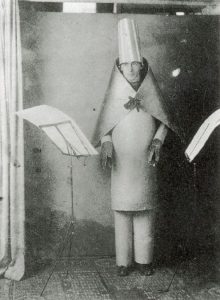

In the realm of performance, the degree of prankishness can also be elusive. When Hugo Ball, dressed in a Cubist costume designed by Marcel Janco, recited his “sound poems” at the Cabaret Voltaire in 1916, he gave birth not only to Dada but to legions of superficially nonsensical acts by artists, from the Happenings of the late 1950s to Nam June Paik’s TV Cello to Gilbert & George performances as singing sculptures. Yet these were all very different in content and impact, and beginning with Ball sometimes offered a response to an incomprehensible political climate. “A logical system of European alliances made all the sense in the world until the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, and then everything seemed to have a domino effect,” says Nauman. The performers at the Cabaret Voltaire, he adds, were “intentionally going for something primitive,” a provocative act that seemed totally in keeping with a world gone mad.

Many street performances today, though their perpetrators may not think of themselves as artists, are also cagily veiled critiques of the political and socio-economic climate. The Reverend Billy stages interventions to urge people to turn the tide of consumerism and stop spending money on junk. An anonymous street-theater group posed as unemployed bankers and performed on Wall Street, offering twenty-dollar hugs and carrying signs that pleaded “Please Bail Us Out.” Those who prank in the name of art also have a more serious message, witness the Guerilla Girls’ endless campaign to draw attention to sexist biases in museums and galleries.

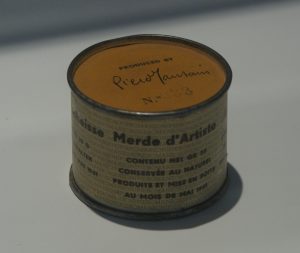

Indeed, many artist “jokes” seem designed to tweak or critique the art establishment or the marketplace. Jasper Johns’s cast-bronze beer cans were reportedly crafted in response to Willem de Kooning’s remark: “That son of a bitch Castelli. You could give him two beer cans and he could sell them.” Piero Manzoni’s Merda d’artista (1961), a numbered edition of 90 cans of the artist’ feces, pokes fun at the avidity of some collectors. “If collectors want something intimate, really personal to the artist, there’s the artist’s own shit, that is really his,” Manzoni wrote to the artist Ben Vautrier. In 1989, Andrea Fraser posed as a histrionic curator the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the highlights of whose tour included a drinking fountain (shades of Duchamp?) and the cafeteria; 25 years later, she filmed a 60-minute video of herself having sex with an unnamed art collector. (Her career, notes critic Holland Cotter, “has been built on asking tough, potentially embarrassing questions of institutions.”)

“The prank can be a way to reveal deeper truths,” says Lyons, which sounds like a variation on Freud’s observation that “the effect of a joke comes about through bewilderment being succeeded by illumination” in his Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious. In the art of the last 100 years, pranks and jokes have gone from sophomoric donkey’s tail peinture to ever more sophisticated foolery, assuming all the permutations of art making today: performance, activism, street art, subversive gestures, and in-your-face challenges to the status quo. Why the last century has been an especially fertile one for mischief is open to question. Perhaps, beginning with the Cabaret Voltaire, artists started responding to the onslaught of disaster and mayhem in recent history. Perhaps, as art historian Simon Anderson from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago—one of the panelists at the CAA convention—observes, the whole trend has been aided and abetted by the news media, which “has become ever larger and ever more avaricious,” he says, “willing to swallow whole huge lumps of pap fed to them by artists.”

Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors (1533). The anamorphic skull is in the lower part of the canvas

But he also points out that we really don’t know too much about the prankishness of earlier eras. “I think there are jokes going on throughout the history of painting,” he says, citing the anamorphic skull in Holbein’s portrait The Ambassadors (seen from an angle, the skull appears perfectly formed; head-on it is an almost incomprehensible and intrusive shape in the lower portion of the composition). Trompe l’oeil, as old as Greek painting, may be another kind of pranking, or it may be simply a virtuoso display of the artist’s skill. Other art historians say the changing notion of who the artist is and what he or she produces is unique to our times. “In order for a prank to really function as art,” says Sarah Archino, another CAA panelist and an art historian at University of California, Santa Cruz, “you have to have the possibility of a lowbrow aspect in art, and if that really existed before the 20th century, it’s been obscured by history.”

So if the “prank theory” proposed by Lyons is to take hold in the academic and critical community, it faces a broad and uncharted landscape. And the first to systematize its tenets, in a style perhaps reminiscent of a rank-and-file deconstructionist or a Marxist art historian, may prove the lowest prankster of all. Because the joke that has to be explained is just not much of a joke at all.

Ann Landi

Top: Damien Hirst, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991)