Dora Dillistone

“These are literal landscapes,” says Dora Dillistone of the works on paper that have been her focus for the past few years. “They’re made by the land and the elements and can never be repeated. I’m just the coordinator.”

The artist “makes” each painting by hauling large sturdy sheets of watercolor paper outside, anchoring them with rocks in favored spots near her home and studio in Taos, NM, and then waiting for the snow to melt or the rain to fall. The results are often magical: earth tones melt into mountainous shapes resembling those in Chinese landscapes from another century, or sometimes an unintended figure seems to be dancing through the veils of subtle color. But beyond occasionally adding small stamps in the shape of Chinese characters or fugitive inks from an eye dropper, Dillistone does little to alter the look of a work after Nature has had her way. Penciled coordinates, written on an edge of the paper, are taken from her cell phone and show when and where the “literal landscape” happened.

At a certain point in her evolution as an artist, she says, “I started moving outdoors. I decided that contrary to what everyone else seemed to be doing—going high tech—I wanted to step away and let the marks be made by the land itself, and the elements.” It’s what she calls “caveman painting,” using the oldest original pigment: dirt. And she’s found a particularly choice spot down the road where there’s a layer of natural charcoal.

As a child growing up in Beaumont, TX, Dillistone was destined for a career as a classical musician. Then, at the University of Houston, she discovered that the course of instruction was way too rigid “to be a performing artist and play with a symphony.” It was a heady time on campuses nationwide. “So much was going on—protests against Vietnam, the Civil Rights and feminist movements—and the campus was so alive. That’s partly how I ended up in art, being surrounded by so much energy and so much creativity.”

But the course of study was by and large a traditional one, as it was in many of her graduate courses at Texas Tech and the Glassell School at the Museum of Fine Arts. “Still, all the way along you’re acquiring knowledge,” she notes.

It wasn’t until the mid-1990s in Houston that Dillistone began making the works that indirectly led to an impatience with conventional ways of painting and then to the present-day series she calls “En Plein Air: Earth, Wind, and Fire.” In Houston, she started studying with a Chinese brush instructor and became intrigued with the spontaneity and the flow of ink on paper. That course of instruction lasted a decade. “It takes a long time to learn how to load a brush,” she notes wryly. Between the mid-1990s up until about 2004, she made a group of paintings in layered colors, one on top of another, from which parts of a female nude emerged. “I wanted to get away from brushes at that point, so I was using sandpaper and rags to get at an image.”

Her latest works, though seemingly unrelated, are a natural progression from a fascination with the behavior of a liquid substance on paper and conventional ways of realizing a painting. “The Chinese paper paintings opened the door to working on paper,” she notes, “and paper is extremely susceptible to water and marks.” The other idea set in motion had to do with giving up control: ”Trying to make art without really making art.” Even the drops of colored ink have come to seem to her “contrived,” and she has left off with that bit of manual interference.

Though Nature is a big part of her process, Dillistone nonetheless keeps regular studio hours, where she spends time reading, researching, and “doing an enormous amount of preliminary work” so that the paper will hold up in the rain and wind (even so, about 30 percent of the “dirtscapes” get destroyed by the elements or don’t pass muster with the artist). Once she hauls the paper back to her studio, it then takes a minimum of a can of fixative to hold the materials together, because dirt and charcoal are in essence just like other friable graphic mediums.

The last two decades have been a period of ceaseless experimentation for the artist, who has also made drawings determined solely by the movements of the wind. To complete all the classic four elements—earth, air, wind, and fire—next on the agenda is experimentation with gun powder. But first, she says, she has to figure out a way to ignite the stuff without blowing herself up.

Ann Landi

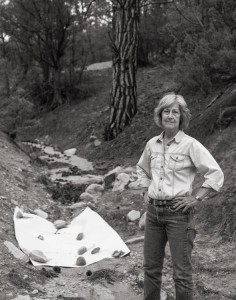

Dora Dillistone gets primed to make a “literal landscape.” More about her work can be found at www.doradillistone.com.

Dora Dillistone gets primed to make a “literal landscape.” More about her work can be found at www.doradillistone.com.

Top: Untitled Landscape, dirt, dry pigment, driven by rain on paper, 45 by 57 inches. Photo of Dora Dillistone by Paul O’Connor.

Ann, loved this, I have seen Dillistone’s work at a few shows in Taos and she is one of the few artists here that interest me. Andy Goldsworthy does pieces some what like these with snowballs on paper. My work has lots of chance built into it, but unlike Dora I still need to have my hand in it as well. I do like the idea of being in partnership with nature and it is an exciting way to work.

You are quite right, Jim. I tried to figure out a way to work that lineage into the piece. Thanks for doing it for me!

Borrowing from the title of a book about Duchamp’s work, I can’t help but think of “the Aesthetics of Chance.” Thank you, Ann, for introducing me to Dora Dillistone’s work.

A very interesting piece on the history of Dora’s process and how she combines an experimental approach using the natural landscape with a documentation of scientific information on the work. Her pieces are both beautiful and fragile.

Wonderful work! Thanks so much for featuring this artist!

Stunning work – love how Dora and paper together create a conduit for nature’s beautiful flowing expressions to surface.