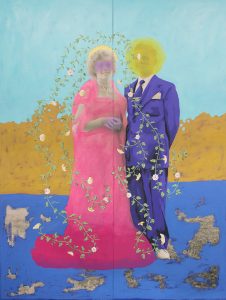

Daisy Patton’s cheerfully dysfunctional portraits are bound to remind you of pictures from somebody’s attic, those old crinkle-edged Kodak photos or studio shots that commemorate engagements, high-school graduations, and informal family get-togethers. Yet there are sharp and unsettling differences. Faces may be obliterated with garish masks of color; outrageous patterns take over sedate everyday attire; or creeping vegetation may threaten to engulf the unsuspecting subjects.

A fascination with photography’s slippery documentary function, and with the artist’s role as voyeur, have been ongoing concerns for Patton even before receiving her MFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and Tufts University in Boston in 2011. In little more than seven years she’s produced several striking bodies of work, a few of which are still ongoing.

Though it’s not blatantly evident her art—that distorted extended family is not her own, after all—Patton’s childhood and education have left their mark. She was raised in Los Angeles, one of two daughters of a single mother, and to this day has no idea who her father was. “We grew up poor,” she says. “We were on welfare and living on my mother’s student loans.”

And yet, she adds, “growing up without a father was one of the nicest things that ever happened. I was always very assertive and tomboy-ish, and I didn’t have to deal with gender roles until I was much older. For that I’m grateful.” (One body of work, her thesis for grad school, is called “I’m Perfectly Fine Without You” and offers up the testimony of others who were raised without a biological father.)

A year before the Rodney King beating tore the city apart, the family moved to Bethany, on the outskirts of Oklahoma City, so that her mother could earn a teaching degree from the university. Then she moved her daughters back to California, to Bakersfield, in 1996, where Patton completed her first year of high school. Then it was back to Bethany to finish out high school. At the age of 13, the artist started reading Shakespeare, specifically the history plays, and “got seriously into British history from the 1400s to the Napoleonic era.” At the same time she was drawing and learning to paint, “though I thought I’d never get a job as an artist.”

In 2001, after her second year of college at Oklahoma University, Patton was accepted into an exchange program with the University of Hertfordshire in England. Before that trip, she knew little of contemporary art or artists but in London saw some of Marlene Dumas’ paintings. “That really shifted my thinking,” she recalls. At college, she started taking upper-level studio courses, but in her last year or two suffered a painting block. “One day I woke up and I simply couldn’t paint. Everything was coming out badly.”

Instead of heading off for an advanced degree after graduation, Patton spent three years working a variety of odd jobs—as an art coordinator for a screen-printing and embroidery company, as an apartment manager, and as a caterer and a gallery assistant. She devoted her free time to taking photographs and was able to put together a sufficiently impressive portfolio to gain admission to the Boston Museum School.

In 2010, during her second year of grad school, Patton woke up with blurry double vision. She managed to get to class by holding on to the edges of buildings, but her adviser, who was also teaching that day, promptly took her to a doctor, who had her admitted to the hospital. There she was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. “There are lesions in the brain that slowly eat away at your neural pathways,” as she explains the disease. “Different people have different outcomes. I’ve had it now for seven years.” The worst side effect, she says, is that high temperatures are difficult because she can get overheated and ends up sluggish and tired.

Five years ago, Patton and her husband, Henry Suarez, who is in a PhD program in science education, moved to the Denver area. The last few years have been extremely rewarding ones for the artist. It was in March of 2014 that she first stumbled upon a stash of abandoned family photos in a store selling vintage items. “I figured out how to enlarge them, print them out to life size, and then paint over them,” she says. And that led to the ongoing series “Forgetting is so long,,” named for a line in a Pablo Neruda poem. In September of 2014, Patton started a two-year residency with RedLine, an ambitious contemporary arts center in Denver, marking the first time she had a professional studio outside her home. “The wonderful thing about RedLine is that your studio is open to the public,” she notes. “So I had an opportunity to talk about my work with a variety of audiences, from curators and critics to people who have no knowledge of art whatsoever.”

During the past few years, partly in response to the alarmingly conservative political tide, Patton has been developing two series about reproductive rights—specifically the issues of illegal abortion and forced sterilization (between 1907 and 1963, some 64,000 people were forcibly sterilized under eugenic legislation in the U.S.). “These issues are two sides of the same coin,” she says. “The general public doesn’t remember how awful it was before Roe v Wade, how many women died from abortions. I’m doing a lot of research, trying to find pictures of women and seeking out women who may still be alive who suffered forced sterilization.” The projects are not yet on her website, but the dialogue between painting and photography will continue. “I need more time and I need to be careful about my role as an artist, to be sure I’m not inadvertently causing more pain than people have already experienced. I’m very careful about trauma and what I can do to amplify people’s voices.”

Patton at her exhibition at RedLine, “Nice Work if You Can Get It,” with Untitled (Sunshine Quality Apr 10 1934 Never Fade)

Ann Landi

Top: Untitled (Five Patterned Women), 2016, oil on archival print mounted on panel, 72 by 72 inches

I love Daisy’s work; the combination of photography and painting is very compelling.

Nice article. I enjoy the odd mystery of Patton’s paintings.