On Confronting the New, the Strange, and the Downright Baffling

It’s become almost a cliché to say that there is no such thing as an avant-garde anymore, because the term “avant-garde” of necessity implies a notion of beyond the pale, difficult to comprehend, and perhaps provoking a sense of outrage. No sooner does an “outrageous” work of art hit the galleries than it becomes absorbed into the canon. Damien Hirst’s shark? No problem. Give it a few years and it will be on loan to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, getting a nod of approval from the magisterial Philippe de Montebello. Marina Abramović wants to live in a gallery without eating or speaking for twelve days? Hey, great idea. Less than a decade later she’ll get a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art.

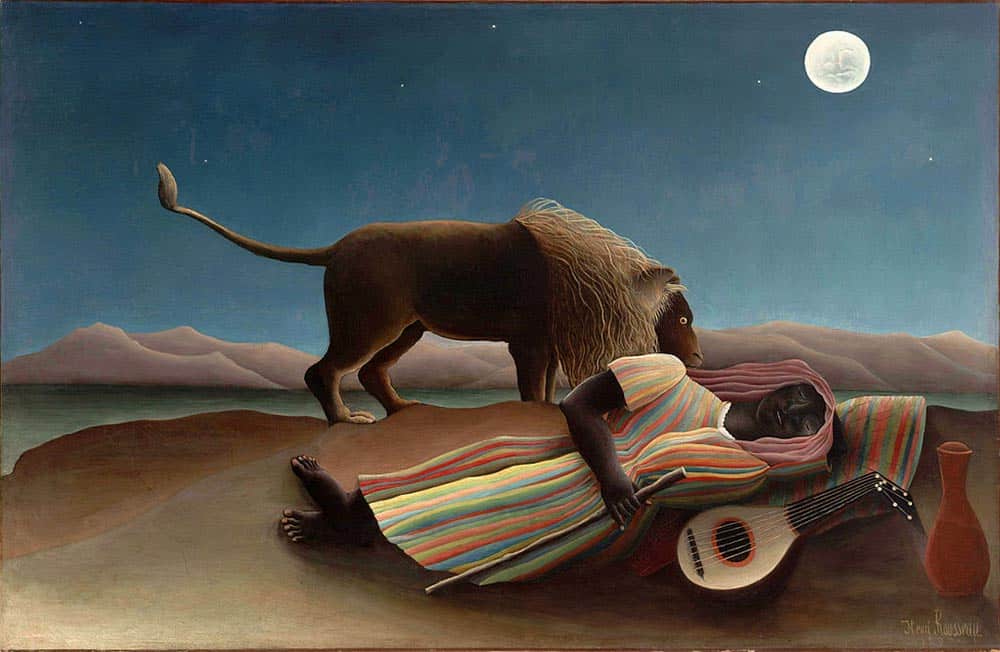

I am not passing judgment on these works. That’s a matter for the critic or the individual art aficionado. I am only noting the speed with which the cutting edge becomes the commonplace nowadays. Picasso kept his Demoiselles d’Avignon hidden from public view for nine years because even his most daring and experimental friends, like Henri Matisse, considered it way too over the top. The deeply eccentric Douanier Rousseau, author of works now given pride of place in collections around the world, got bad reviews year after year and could not make a living from his paintings. And let’s not even go into van Gogh. So many brilliant members of the avant-garde from years past—when there really was an avant-garde—never earned widespread acceptance in their lifetimes.

But times have changed. In my decades as an adult, not always writing about art but at least conscious of it, Vito Acconci masturbated for eight hours a day under a ramp in a gallery, Chris Burden shot himself in the arm, Carolee Schneemann extracted a paper scroll from her vagina, Vanessa Beecroft positioned 15 nude models in the Guggenheim So really, dear, do you think plopping a pair of fried eggs on your T-shirt, atop your breasts, can be called a radical act? A gesture of the avant-garde?

In the course of reporting or reviewing in the art world, the writer expects to bump up against the new and the strange. That’s just part of one’s beat. What interests me is not whether I’m offended or confounded, but whether I can come to some sort of understanding, an aha! moment. And this is where it’s much more fun being a reporter than a critic. You get to talk to the artist and gain some insights into what’s going on. When I first saw Tony Oursler’s beguiling but crude little puppet-like dolls, whose faces were disturbing video projections of angry or troubled adults, I was intrigued but perplexed. After talking to him for a while, learning about his childhood and his darker years struggling with alcohol and drugs, seeing all the complicated technology that went into shooting and editing video, I came away with both understanding and admiration.

Similarly Nari Ward’s installations left me befuddled and even a bit annoyed. What was the damn stuffed fox doing on the tactical platform that was part of a show at Lehmann Maupin? What was the platform doing there in the first place? What was that ladder made out shoelaces that crept upward to a false trap door in the ceiling? Then I got a chance to talk to him about his experiences as a young black artist living in a dangerous pocket of Harlem, after a relatively benign childhood in Jamaica and New Jersey. “I was reacting to the richness of the narratives there, the stories, the loss, the urban blight,” he said. “I felt there was a voice that wasn’t being addressed, and I just started working with found objects.”

So much contemporary art requires back story. It’s often easier to grasp a painting or a sculpture that’s been made along more or less conventional lines, but many other works are hugely enriched by understanding more about what’s going on in the artist’s head. The ladder and trap door, for instance, were a remembrance from Ward’s childhood. “When I was in grade school, when we moved from Jamaica to New Jersey, we had this house, and the only place I had that was my own was in the attic,” the artist told me three years ago. “It was this little tiny space, and I remember pulling down a ladder to get to it.”

And all of this leads me to Brian McCutcheon, who is “Under the Radar” this week. I wrote very briefly about McCutcheon for an ARTnews story called “Out of This World,” and then about his experiences with rejection for the recent two-parter on the subject, and realized I wanted to know more. After looking at his website, I was having trouble connecting the dots—how did that funny ceramic figurine splashed with automotive paint lead to a “customized” Weber grill which then led into an ambitious project in many mediums about the Apollo moon launch? After talking with him for 45 minutes (and I wish I could have flown to Indianapolis for a studio visit), I began to see the thread that took him from one work to another.

That doesn’t mean I can comprehend everything I see out there. And what’s “out there” doesn’t signal a regeneration of the “shocking” avant-garde of a century ago. But if we can come away with a more enlightened view about what serious artists are doing with their time and talents, we can possibly apply that patience and willingness to learn to other facets of our lives. We can question and probe, we can accept or reject. But at least we’ll have the satisfaction of knowing we tried to understand.

Ann Landi

Photo credits: Nari Ward, Bottle Messenger, courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong.

I can’t tell you how much I enjoyed your thoughts presented in this article, nor how many times I’ve tried to explain where my art was “coming from.” I long for a time when art becomes part of everyone’s life….when an art vocabulary is so prevalent, we can understand each other when looking and speaking about art – person to person, not artist to non-artist. Wouldn’t that be loverly!!!

Ann, I totally agree, even if I really dislike something I try to dig deeper and see if I can understand the work better and I have usually fallen in love with the work after putting forth the effort.

Just Brava!! a thousand times for writing with such authenticity and such respect for your subject and inquiry.

You’ve hit the nail on the head: understanding art takes patience, and sometimes lot of it. Thanks for putting it so clearly and cleverly.