In the 18th and 19th centuries, history painting was considered the loftiest genre to which a European or American artist could aspire. High drama from ancient and contemporary events—battle scenes or coronations, for instance—inspired painters to produce grandiose canvases crammed to bursting until the taste shifted toward the more modest subjects favored by the Impressionists. As the Tate Gallery website notes, “The role of history painting was to plummet even further in the 20th century, disappearing almost entirely from art circles following the breakup of empire after the Second World War.”

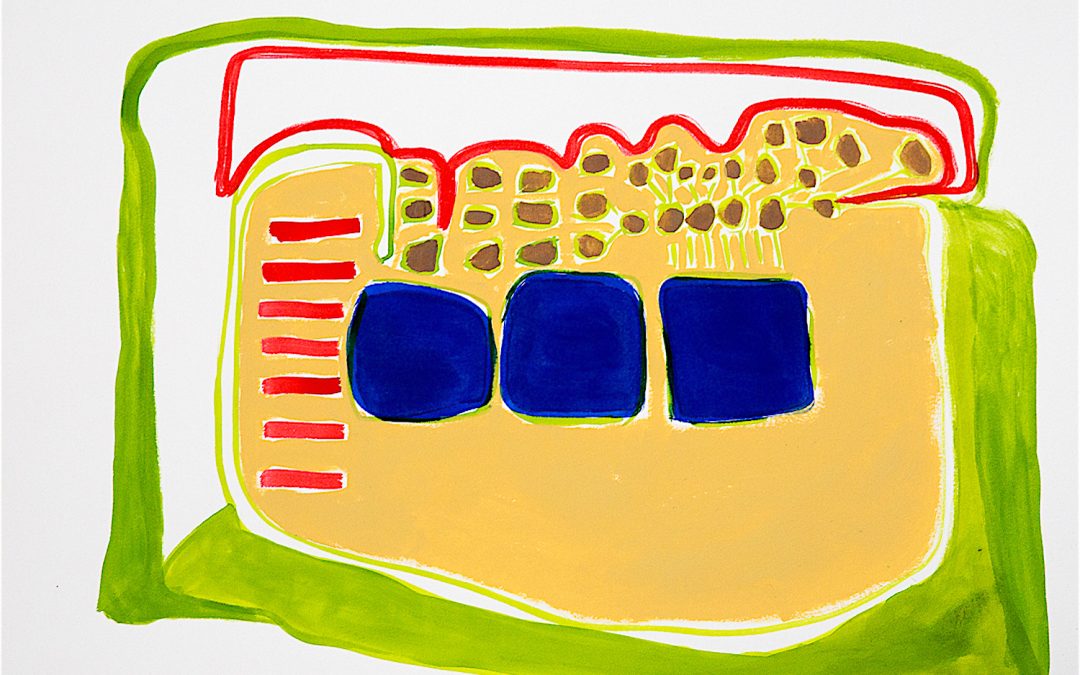

So it’s oddly refreshing to find an artist like Carole D’Inverno totally re-inventing the idiom, putting her own spin on history and telling stories in a largely abstract language. Take, for example, her canvas Mrs. Minnie Mossman from 2016 The work celebrates a little-known 19th-century heroine, the first female steamboat captain on the Columbia River estuary in the Pacific Northwest. The painting finds its imagery in rudimentary suggestions of old maritime equipment like sextants and a compass, while the fine white lines allude to the ivory bones that used to be fitted into women’s corsets.

“I’m interested in history at the local level,” D’Inverno says. “What is its impact on regular people.” For the series called “Far West,” which includes Mrs. Minnie Mossman, the artist says she “spent weeks learning all the information I needed, making sketches and writing notes. Finally I put all the information aside and then let the art happen.”

For D’Inverno, a fascination with history may start with her childhood in Europe, which still in the 1960s felt the aftershocks of World War II, “but nobody would talk about it,” she says. Her father was a jazz musician, and both her parents worked at odd jobs as the family moved around a lot between Belgium and Italy, finally settling in Brussels when the artist was 13.

Growing up in Europe, she describes herself as “clobbered with art—everything was a masterpiece, but I couldn’t relate to any of it.” The artists who most attracted her from a young age were the members of the European avant-garde, like Miró and Kandinsky. “I was in the process of accepting how I saw the world, that I see things very flat.

“I was always drawing abstractions from a young age, without even knowing what these were. It was very instinctive for me,” she adds. D’Inverno took art classes here and there in life drawing and painted figuratively for a while, even though that approach didn’t resonate with her. She also studied chemistry at the college level, taking art classes whenever she could. “I was slowly trying to carve out time for myself because I knew I was going to keep doing this.”

When she was 22 and working in the town of Spa in Belgium, she met her husband, Bill Frisell, a composer and jazz musician (as is her brother!). A year later, they moved to the States, to Hoboken, NJ, just outside New York City. For the next ten years D’Inverno worked at a number of jobs, including her first one in a kosher-food factory. “I could talk to the workers because they spoke Spanish and I spoke Italian, and there was enough common ground to make ourselves understood,” she recalls. “I worked my way up to making cabbage rolls because in that job I could sit down with the Polish ladies.”

For a couple of years she also worked as a nurse’s aide. “It was rewarding because I got to meet a part of the population I never would otherwise. So I’m grateful—that kept me anchored in a kind of reality, that sense of understanding what all these different people seek.

“Since I was little I thought I would get to the point where I can do what I love to do,” she continues. “But I knew it would take me a while. In my spare time, I was drawing and painting.”

D’Inverno was still making figurative work when she and her husband and then-four-year-old daughter moved to Seattle in 1989. “Up till about ten years ago, I had barely started to doing work that could amount to something,” she confesses. “I knew I was going to be an artist but I simply didn’t know when. I kept saying to myself, Just keep working, don’t give it up. The drive was always there, I just needed to keep feeding it a little bit.”

In 2011, she produced a body of work called “Three Wheels Broke” that appears in many ways to be transitional. The title of the series and of some of the works (“Prairie Schooner,” e.g.)—all paintings in oil on canvas, a couple as large as four by six feet—alludes to the epic westward trek of settlers in covered wagons. But in an artist’s statement, D’Inverno cites the distressed surfaces of the architecture that surrounded her in Europe and the “lusciousness of nature” in Seattle as other influences.

In recent years she has turned to “excavating” in her own way the histories of places as diverse as Rochester, NY, and Appalachia. In her studio are works from a series still in progress called “Transumanza” (as well as bookshelves crammed with biographies and history books), which, she explains, is an Italian term for “a traditional twice-yearly migration when shepherds drive their flocks from the highlands to the lowlands, and vice versa. The word literally means ‘crossing the land.’” In 18 months, when she has a residency at the Maitland Art and History Museums in Maitland, Florida, she’ll turn her attention to the history of that area.

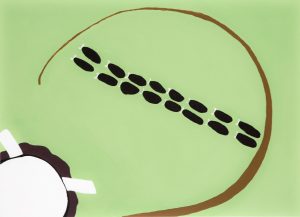

Her process at first seems somewhat baffling, but as explained on her website and in conversation it amounts to a form of imaginative distillation: “To prepare for a new series, I extensively research a place, a time period, an event,” she writes. “From the information gathered, I then develop a visual coded language with repetitive motifs, patterns and colors specific to the subject I am working on. As I proceed, the language morphs into a unique melding of imagination and facts. Each piece produced is free of direct reference but underpinned by the original information.”

The viewer might guess at the imagery here and there (are those footprints in Walking Times?), but D’Inverno’s sprightly shapes and colors—like those of her childhood heroes, Miró and Kandinsky—hold up nicely on their own, without literal interpretation.

Ann Landi

Top: Untitled No. 14 (2016), ink and watercolor on paper, 22 by 30 inches

Interesting work, and story – a window into the way life feeds and informs work. Also, I share the feeling that working with people in non-elite settings can expand your circle of empathy, and understanding of life.

Thanks for introducing me to Carole’s work! Wonderful!