As Hurricane Katrina approached New Orleans in late August 2005, Brandon Graving, whose studio was in the uptown Riverbend area, calmly thought to herself, “Well, I’ve lived through hurricanes, so I’ll survive this one.” By that Saturday, though, it was clear that this tempest was unlike anything she’d seen before and she would have to get out of town fast. “I started packing my truck with all the most insane stuff possible,” she recalls. “I brought my mother’s silver, which is what you do as a good Southern woman, and all the stuff for my dog, but I totally neglected to pack appropriate clothes and it didn’t occur to me to make reservations anywhere. Fortunately, I had gassed up the truck on Friday or I never would have been able to get far.”

Graving headed toward family in Florida and made it to safety, but her studio and all her work there were completely destroyed.

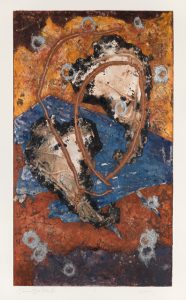

The good news was that her large installation in the New Orleans Museum of Art, a 30-foot long print called Ephemera (above), shown in tandem with a driftwood sculpture atop a pile of sand, survived the deluge with no damage whatsoever because 18 of the museum guards stayed behind to watch over the collection. Indeed it was later purchased by the Frederick R. Weisman Foundation and went on to travel to 15 different museums. Today Ephemera still ranks as the largest monoprint made by a single artist.

Graving eventually resumed her divided existence, spending part of the year in New Orleans, and the other half in North Adams, MA, where she is the master printmaker with Gravity Press, working on her own sculptures and prints and helping other artists realize their books and projects.

But her deepest roots are in New Orleans, where she was born and given up for adoption as a baby. “The people I grew up with were amazing,” she says. “My dad was an FBI agent, and his powers of observation were one of the main things that turned me into an artist. I imagined that he could know things just by looking and watching. I think that was a big contributing factor to my interest in the visible world.”

When Graving was in the third grade, her mother was diagnosed with cancer and died four years later. “She was a fierce, brilliant woman,” she recalls. Hoping to help ease her pain, the artist drew pictures—“of luna moths in particular,” big celadon-green insects that live only for 24 hours. “I didn’t think the drawings would fix her or heal her, but I really thought they would help somehow.”

When her father remarried, Graving dropped out of high school and left home at the age of 13. She lived with different people, recalling some “sketchy situations here and there,” but eventually made up her classwork in summer school and graduated on time. “It was like a novella,” she says, “but it turns out I have an extremely high IQ, and that proved to be helpful.”

After a year at Loyola University in New Orleans, she transferred to the University of Louisiana in Lafayette, where she studied with Tom Secrest, a dedicated draftsman who encouraged her interest in printmaking. She discovered sculpture too, and found that the “combination of drawing and sculpture was perfect for me”—two passions that continue to this day.

She worked as a studio assistant after graduating, for artists like Rodney Ripps, Lin Emery, and Bill Ludwig, and showed in local galleries. While still a student, she decided she would have to change her name from Suzanne Brandon Graving to Brandon Graving. “The organizers of one show spelled my name so oddly that I realized I would have to simplify it. So I ended up with Brandon—a name I’d liked since the third grade.”

In her late 20s, Graving lived in Cameroon, Africa, for three and a half years, joining a musician boyfriend who was there to finish a book. “It was exotic and amazing,” she recalls. “I was consistently making very small things out of materials I found there, like local graphite and the camwood that’s rubbed on a young woman’s skin before she gets married. I did a lot of pieces on the ground, and an installation that had to be left behind.”

On her return to the States, and after her break with her beau, Graving decided she should pursue an artist’s residency and applied to a contemporary arts center in North Adams. “I wanted more of a dialogue with other artists,” she says. The residency was in the building where she still maintains her studio, home, and printmaking business. That first year saw a remarkable number of visitors—curator Walter Hopps, Julian Schnabel, Sam Gilliam and others. Graving rapidly transitioned into a job as a gallery coordinator and gallery director, and then as an assistant to the master printmaker.

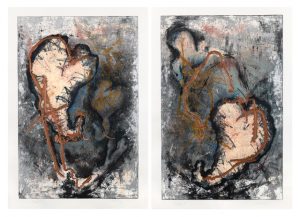

Her specialty is large-scale monoprints, and she describes her own endeavors on her website: “The three-dimensionality of the print is actual,” she writes. “The various plates and objects leave behind an impression embossed in the paper, and the press forces the different viscosity of inks through the paper, from hugging deep into the fibers to resting on the surface. The viewer, rewarded for coming in close, can decipher the layers and see the history of the decisions that make up the work.”

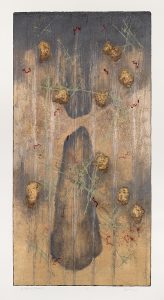

The other aspect of her practice is everywhere in evidence throughout her cheerfully jumbled upstairs studio: magical sculptures suspended from the ceiling or mounted on the wall. As long as three feet, these are made from abaca, a fast-growing species of banana plant, which comes in big sheets. Graving tears these to small pieces, moistens them and secures those to armatures. She then attaches bits of vellum in different colors. Light enough to move in response to ambient motion, the final sculptures seem to belong to a strange realm of the botanical world, possibly aquatic, and to some the artist has affixed droplets made from crystal, like morning dew on outdoor vegetation.

“I think of a piece of paper sculpturally, so the monoprints with their embossed surfaces and different viscosities of inks have a presence unlike other prints,” she says. The sculptures, meanwhile, capture the transience and translucence we often associate with paper mediums. “When I show the work together, they inform each other in unexpected ways.” And as she adds in her artist’s statement: “All of these works attempt to describe an aspect of humanness, with great attention to the natural world.”

Ann Landi

Top: Brandon Graving, Ephemera: River with Flowers, embossed monoprint on paper with blasting sand and river sticks

(sculpture dimensions variable), 2004, 10.5 feet by 32 feet; collection of Frederick R. Weismann Art Foundation

>

>

What an amazing life story, Brandon. It was so wonderful to finally meet you and I look forward to growing our friendship. Your are a resilient woman and artist.

Wonderful work and story.

Fabulous work Brandon! And such an interesting life story. Thanks for sharing it Ann.

Beautiful article and so deserved . The sculptures are my favorite a reflection of your spiritual journey . I remember our long discussions about how our lives evolve. I hope to get your way sometime in the next year, my grandson is interviewing at Williams College in June.

Congratulations on this wonderful article. Thanks to Ann,beautiful story for all to read