When August Muth was five or six years old, he would take his drawings, spread them out on the gravel in the driveway of his family’s house in Albuquerque, NM, and sell them to passers-by for three cents each. “I always had a lot of entrepreneurial spirit,” he recalls. But it would be a while before he could study art, and even more years before he would hit on the medium that has occupied him for almost 20 years: shape-shifting and shimmering holograms that change in color and intensity as the viewer moves in front of the works.

“I could never get into the high-school art programs,” he says. “By the time my name came up for registration all the classes were basically taken.” Still, from an early age, he was attracted to the possibilities of glass, and of light. As a teenager he made shapes out of panes of glass, held together with wax and filled with water, and delighted in the way the light sent prisms of color on to the garage doors.

When his brother, Will, opened a crafts and jewelry store in southern New Mexico, Muth decided to forgo college and learn how to make jewelry. He entered the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque a year later and studied physics and astronomy. Looking for a more serious art curriculum, he transferred to the University of Houston, where he studied with James Surls and quickly locked horns with the sculptor, who was then making a name for himself in Texas art circles. “That was the peak of his monolithic period,” Muth recalls. “I was very involved with light at that point.” Surls did not approve, and it soon became evident that it was time to leave. An end-of-year project that incorporated a replica of Superman and some Surls-like appendages did not much endear him to the teacher, or bode well for future studies in Houston.

He transferred to the University of Texas in Austin, where he ended up taking more courses in astronomy and falling in love with a ballet dancer. When she got a job in New York in 1977, he moved with her, and eventually found a studio on East 17th Street, right around the corner from Andy Warhol’s Factory. It was a heady time in New York especially as his partner soon attained some prominence in the dance world. There were evenings at Studio 54, the hot spot for celebrities and so-called jet setters, and the beginnings of performance and video art at the Kitchen, a nonprofit experimental space that is still going strong. Keith Haring became a friend and a kind of role model for how to strike out on your own as an artist. Following his interests in the possibilities of capturing light as an art form, Muth found himself increasingly drawn to the possibilities of holography.

The Museum of Holography had recently opened downtown, and the director of education took the young artist under his wing. “They had an artist-in-residence program,” he recalls, “and invited people to come work on projects. Then there were six to eight weeks in between the arrival of the next artist. They plugged me into the in-between slots and let me use the studio space and holographic facilities. I had a couple of shows in New York but by that point the art world was really into big expressionist paintings.”

After splitting with the girlfriend, Muth stayed on in New York two more years, until 1985, house sitting for friends from the performing arts who were often on tour. But he longed to be out West again and moved to the Aspen area and later to Telluride (the artist was then an avid skier). Together with a business partner, he started a holographic jewelry company. But after seven years, having built himself a studio and learned to work with emulsion, he felt it was time to move on.

In 1992, he moved to Santa Fe, and has been there ever since, in a rabbit-warren of connected studios filled with complicated and mind-boggling pieces of equipment. Patiently he takes me through the process of creating a hologram. “You take a piece of glass with emulsion on it, which is light sensitive and similar to the photographic emulsion that was developed in 1850,” he explains. “It’s placed on top of the subject matter. The laser light goes through the emulsion and then bounces off the subject matter, and then the light waves come back through the emulsion and create an interference pattern, sort of like a moiré structure, little waves, and that creates a micro-terrain in the emulsion.”

Holograms, Muth points out, occur everywhere in nature: in the iridescent patterns of bird feathers, for example, or fish scales or opals or beetles. “Anything in nature that’s iridescent is a kind of holography.”

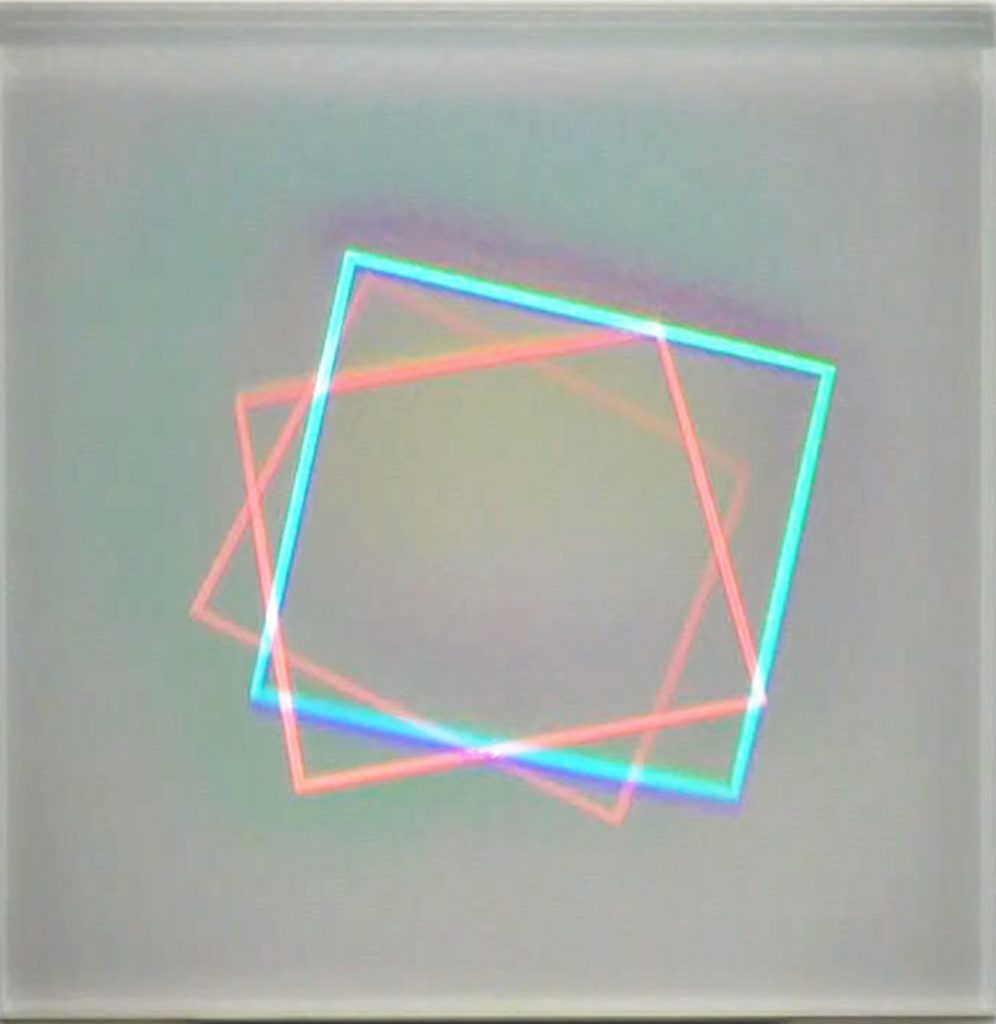

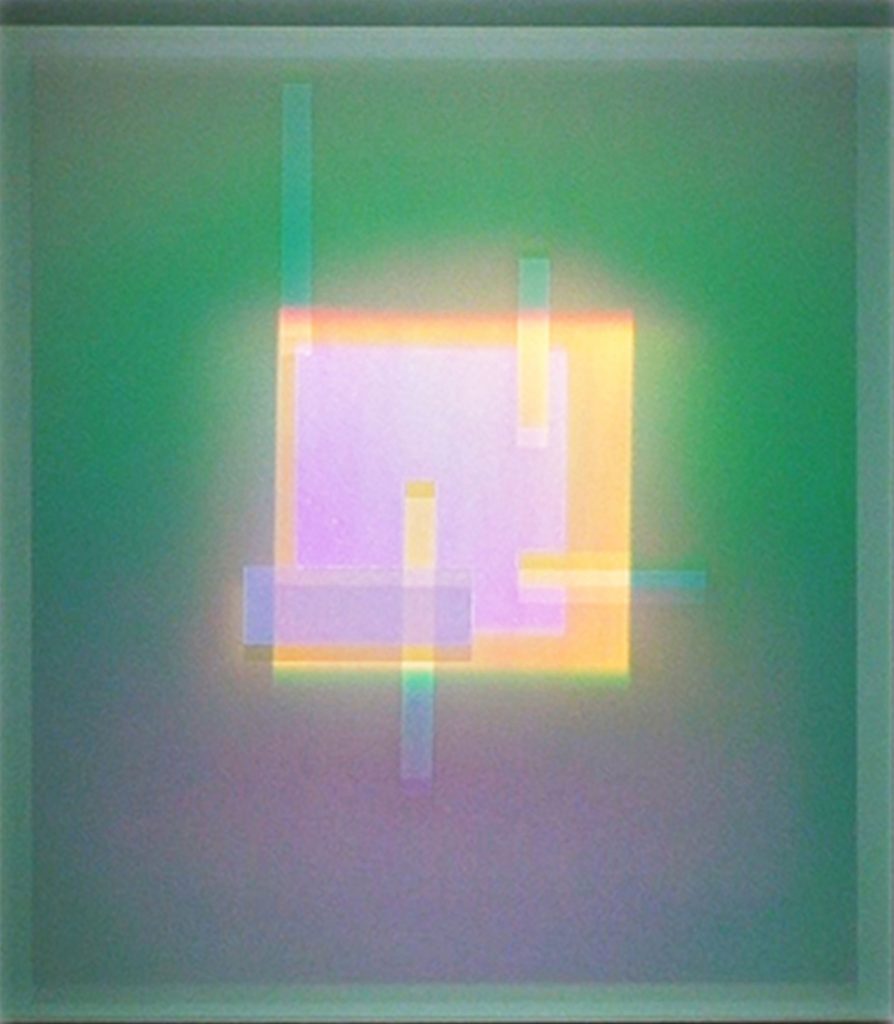

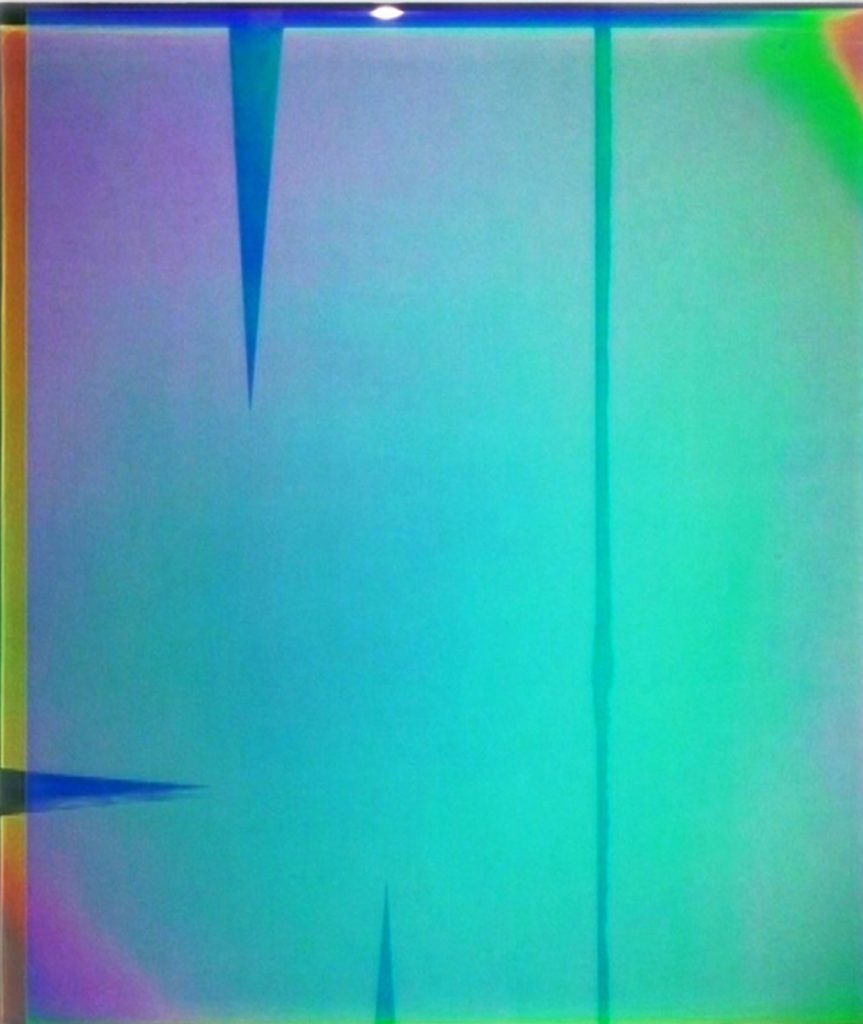

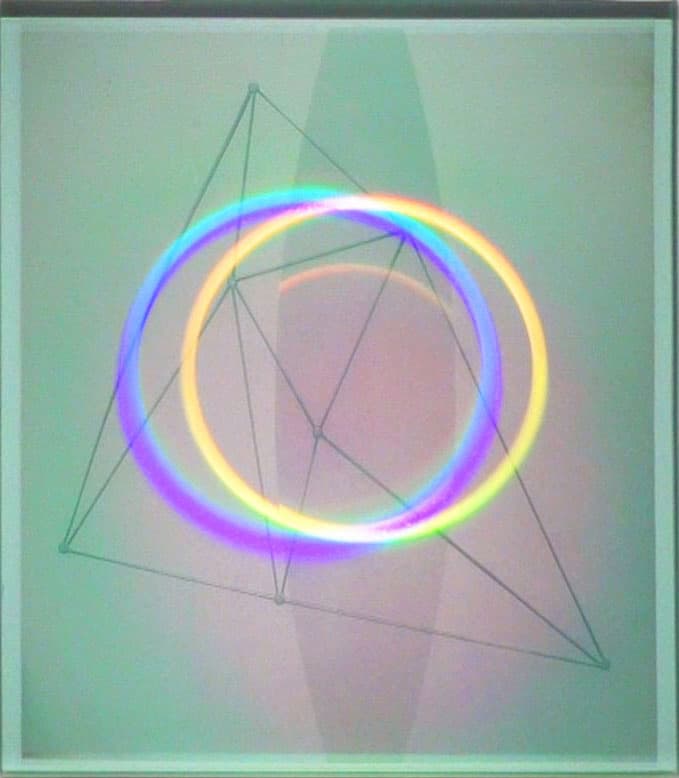

Subject matter can vary, as in photography or painting or other mediums, from portraiture to still life to whatever the artist can aim a laser at. But Muth, since around 2000, has been making abstractions that call to mind Color Field canvases, works by Mark Rothko, or the compositions of certain geometric painters. His palette ranges from subtle pastels to deep blacks to neon-bright primary colors, and he readily admits to the influence of the Abstract Expressionist works he saw in museums as a child. Regrettably, holographic work is hard to reproduce, but a glance at some of Muth’s images on this page gives some idea of the subtleties that can be achieved, and of the shifting depths. Generally, the works are medium-sized rectangles, but the artist has produced some spectacular rhomboids that throw the viewer just slightly off balance in an agreeable way.

So proficient is Muth at the making of holograms that he has worked on about 150 projects for James Turrell, no doubt a boon to his overhead, which can be sizable—a single laser light, he tells me, costs around $38,000.

How, I wondered, did all his study of astronomy and physics in his student days and beyond tie in with his art now? “Time and light are one,” he says. “What we know of the universe is pretty much derived all from light. There are a few meteors that fall on the planet, a little bit of moon dust that we can look at. But 99 percent of what we know, all the information is carried in light.”

Light, of course, is a medium that has captivated artists for centuries, but Muth’s holography captures qualities that confounded even the most adept of painters—its transparency and its sheer elusiveness.

August Muth has exhibited his work nationwide, and internationally at symposiums and art fairs in Milan and St. Petersburg. He is represented by Waterhouse Dodd in New York, NY; Gallery Sonja Roesch in Houston, TX; Chandra Cerrito in Oackland, CA; and Hulse/Warman Gallery in Taos, NM.

.

Terrific work, terrific artist and story. Thank you Ann

August’s work mesmerizes! I so appreciate knowing more about the artist. Thanks a bunch, Ann, for flying under the radar and catching and sharing the flash of August’s laser lights!

Interesting life story Ann. Thank you.

Wow. Even though the images are hard to replicate, the language of the this piece is wonderfully descriptive and makes me want to find a way to see this work in person. Thank you!