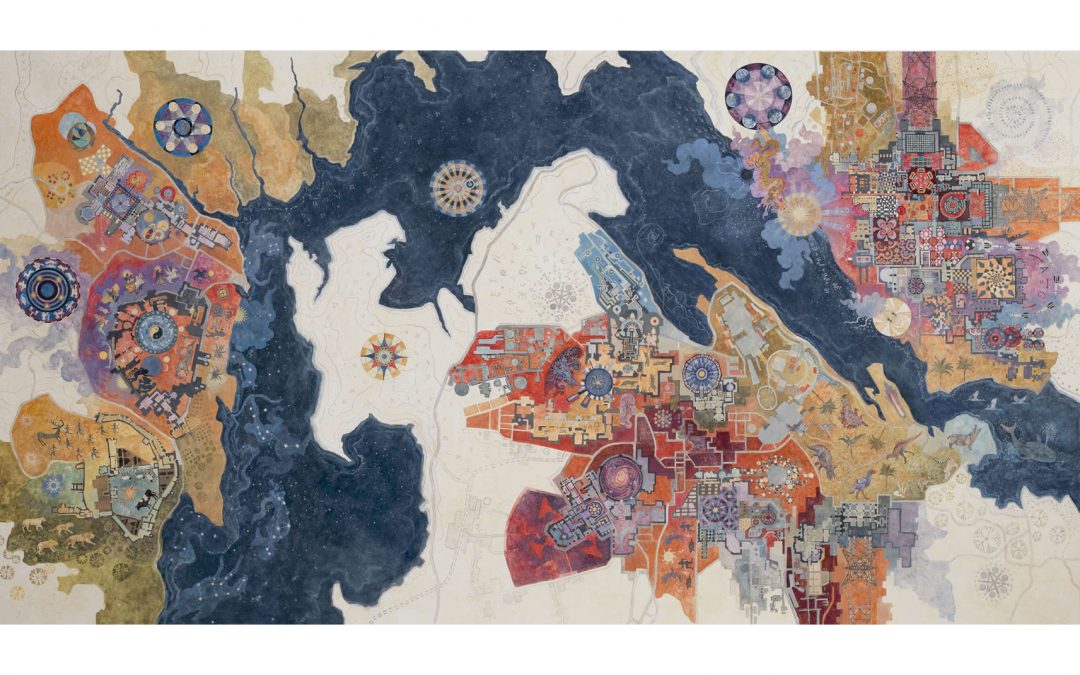

Alison Berry’s recent paintings resemble maps of unknown and fantastical places, enchanted worlds that incorporate beasts both ancient and modern, floor plans for eccentric structures, buildings that look lifted from Quattrocento paintings, lush trees and plants—along with coursing inky-blue channels that might be bodies of water or star-studded swaths of the night sky. It’s a complex, beguiling universe realized in jewel-like colors and breathtakingly fine detail, reminiscent in its richness of Persian miniatures and medieval frescoes.

Berry describes her world as “conceptual cartography” and sees in it attempts to reconcile not only the disparate impulses of history and the modern world but also some of her own life as an artist. From earliest childhood, she was called on to cope with opposing points of view. Born in England, the artist was raised in New York State, the daughter of parents who were both trained as scientists—though one was a devout Episcopalian and the other an outspoken atheist. There were social distinctions to navigate as well. “People don’t often think of the English as having a different culture because we speak mostly the same language,” she says. “But when I was a little kid I spoke with an accent, wore different clothes, and ate different foods. If your mother sends you off to school with a sardine sandwich, you will get teased for that.”

“By the end of high school I felt I had to find out for myself what I really believed.” When Berry arrived at Yale as an undergraduate in the 1970s, she realized there were big gaps in her education. She started as a philosophy major because she loved “reading and thinking about ideas” but eventually gravitated to art. “Ever since I was a child, making pictures was my way of coming to terms with things. There was a great sense of satisfaction about that, and pictures became a way to help me organize my thoughts. And for me there continue to be great rewards in the materiality of art.”

One turning point for Berry as a student came on a travel fellowship to Mexico, where she encountered and made a drawing of a tablet depicting a Mayan ruler and his mother. Pictographs surrounding the main figures showed small animals and symbols that related to the language, and Berry wrote a prize-winning paper about their interpretation. “I found it amazing how much of this intricate culture became known to me through studying the glyphs and the iconography,” she recalls. “I loved that aspect of trying to put a world view into visual images.”

After graduation from Yale, Berry moved to New York, got a job with a restaurant (where she met her future husband, painter Julian Hatton), and attended the New York Studio School for a year. It quickly became apparent that the school’s agenda was at odds with her own goals. The emphasis was still on Abstract Expressionist gestural painting, and, says Berry, “I knew this wasn’t for me.”

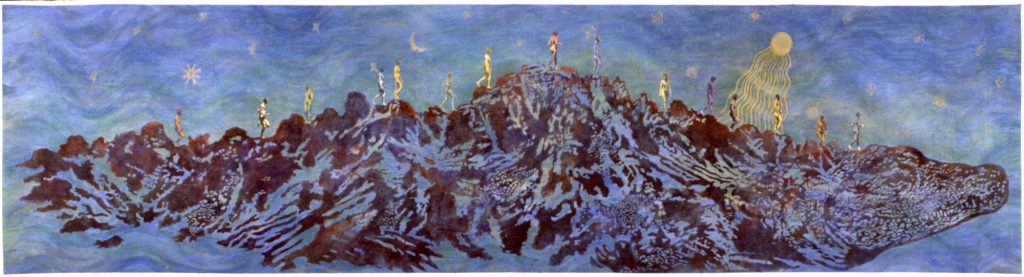

By the mid-1980s she was making large figurative paintings that “focused on questions such as mind-body duality, psychological experience, and transformation.” In 1988 she enrolled at Brooklyn College in the MFA program, completing the degree two years later. She chose the program, she says, “because of its traditional figurative emphasis,” but soon found herself striving to reinvent her work and change some of the conventions that had served as the underpinnings for her art.

The ‘90s were a tough decade. Berry managed to patch together a living as an adjunct instructor for Brooklyn College, a printmaker for other artists, and a painter on architectural projects that required murals or decorative faux finishes. Her marriage foundered, and for a couple of years she and Hatton separated. She stripped down her process to make many small drawings, restricted to a single image with no background, and played around with assembling them into larger pictures, “sourced from art history, social history, scientific diagrams, and magazines and newspapers.”

By 2000 she had held a successful solo show in her loft, attracted a small following of collectors, and been invited to join the Painting Center, a prestigious nonprofit gallery, now in Chelsea. “Things seemed to leap forward, but actually the years 2001 to 2005 were a nadir for me, plagued by illness and injury, and too much commercial work.” Berry was not happy with her shows at the Painting Center. “The ideas were solid, but the compositional and material strategies were not.”

Then in 2005 she experienced what she aptly describes as a “paradigm shift” and began to think of the paintings as maps. In earlier works Berry had combined diagrams with pictorial images; now she mixed plan and elevation, shifting overall to a bird’s-eye view. She also abandoned oil paint, her preferred medium for 30 years, for acrylics, inks, dispersed pigments, and the colored pencil that allows her to get fine detail.

The “conceptual cartography” allows the artist to bring together many interests, at least on a symbolic level—mythology, history, science and the laws of nature, ecology, technology, and the environment. But though the viewer may delight in allowing the eye to travel from each meticulously realized facet to another, the overall look of the “maps” as patterns of color and line and shape is also deeply satisfying from a distance, in much the same way as a knock-out color-field painting.

Response to Berry’s works of the last few years has been growing. She’s had solo shows at Gross McCleaf Gallery in Philadelphia and the Kingsborough Community College Gallery in Manhattan Beach, NY. And in 2015 she landed two large commissions, one for the Emerson Resort in Mt. Tremper, NY, and another for the Vanguard Fund in Malvern, PA.

Her work since her student days, as she notes in a recent grant application, chronicles not only her own quest but also speaks eloquently of humankind’s struggles—from the prehistoric to the present—“to grow beyond tribalism and superstition.”

Ann Landi

Top Image: Voyager (2016), acrylic, ink, pigment on Evolon microfiber 48 by 90 inches

Click on any image to enlarge it.

Alison, I am fascinated by your iconography of mapping – a phenomena and investigation that is at once so archetypal and so intimate. Though we did not get enough time to talk at Arlene’s studio, I enjoyed what conversation we had and look forward to another time. I have found a building in Kingston, NY so I hope to be moved within a year or so…

all best wishes and congratulations on this article by our wonderful Ann Landi