After dropping out of the MFA program at Brooklyn College in her twenties, Jane Shoenfeld stopped painting and using color and spent three years drawing her dreams in black and white. Thus began a process that continues some 40 years later of working from what she sees in the world around her and what emerges from her imagination. A similar seesaw has governed her life as an artist versus the necessity of making a living in the real world. “I didn’t have that sense of myself, as some people do, that I could earn my living as a painter, or by doing my artwork.”

So Shoenfeld has held jobs as a typist, a paste-up assistant, a life model, a graphic designer, and an art therapist. “Even though I didn’t grow up with the American dream, in a number of ways—in the cultural sense—I did grow up with it. I knew I’d always be able to get a job, and I did. This is the land of opportunity.”

She was raised in a nonconformist household, first in Maryland and later in Washington, DC. Her parents were independent-minded card-carrying Communists at a time when that could cost you your livelihood. Shoenfeld’s father was a journalist; her mother wrote short fiction on an old Underwood typewriter. There was a lot of support for an artistic career, but very little money. After a year at George Washington University, the artist transferred to Pratt, where she was presented with two options: training as a teacher or as a graphic artist. “I was horrendously shy and I didn’t want to take courses in teaching,” she recalls. And so she graduated with a degree in graphic arts.

And like many of her generation headed for San Francisco and moved to Haight-Ashbury. “I was a hippie, but I wasn’t heavily into drugs.” For a time she got involved with photography, but for her the “summer of love” lasted only a year. “San Francisco didn’t feel like my home,” she recalls. “New York was my home and at that time I wasn’t ready to be away from my family.”

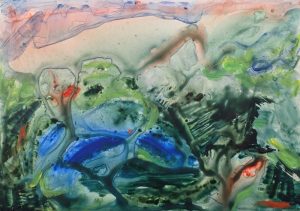

Ten Years After the Fires, Dorland Mountain (2016-17), pastel, acrylic and gel medium on sanded board, 26.5 by 38.5 inches

She landed at Brooklyn College for graduate work, which then leaned toward the figurative tradition, but when it came time to do a thesis, she was told she would have to do more work. “That was devastating at that point, not to be moved into the next slot so that I could complete my degree,” she says. “I wasn’t a complete failure, but I wasn’t a success either.”

From 1970 to ’75, Shoenfeld worked as a designer for Esquire and Grolier’s Encyclopedia, among other publications, and did annual reports and promotional materials for the Junior League of America, where, she says, she “got to design and produce some gorgeous pieces.” But she couldn’t see pursuing graphic arts for the rest of her life and decided to complete a master’s in art therapy at Pratt. That led to employment at a psychiatric hospital on Staten Island for eight years. “While I was doing art therapy with the patients, whom I genuinely liked as people, I started making still lifes at home because it was a very meditative and calming practice by contrast with my day job.”

A residency at VCCA in rural Virginia led to an interest in landscape and a desire to leave behind both the “box of the still life” and the confines of city life. She sublet her place in Brooklyn and moved to Taos, NM, in 1987. “I had been traveling in the Southwest with friends several times. What brought me to New Mexico was the space.” She was in Taos for only nine months when her mother died and left enough of an inheritance that she could turn to painting for five years.

Finding Taos a little “too incestuous,” Shoenfeld moved 70 miles south to Santa Fe, and has been there ever since. Pastel remained a preferred medium for a long time, the landscapes often fusing with a kind of dreamscape reminiscent of Charles Burchfield. And she has been combining pastels with other mediums—watercolor and/or an acrylic ground, for example. Yupo is another recent material, the super-smooth surface offering a new range of suggestions, including figuration. “I paint all the time out at Ghost Ranch [Georgia O’Keeffe’s former studio and home],” she adds. “I have done two self-created residencies out there, where I stayed for three weeks at a shot and painted. Many, many works were either painted plein air at Ghost Ranch or were the inspiration for abstract paintings.”

Jane Shoenfeld with The Vanishing Chronicler of the Disappeared. Her work is currently represented by the First Street Gallery in New York, NY, and the Ralph Greene Free Style Gallery in Albuquerque, NM. She has been teaching workshops to artists and art therapists in New Mexico for 30 years.

Married to an award-winning poet, Donald Levering, Shoenfeld has recently turned to making work that is in response to his poems, which often take as their themes environmental abuses or human rights violations. “There’s a tradition called ekphrastic poetry, wherein poets respond to paintings, and Donald had written some verse in response to my works,” she says. “So now I’m responding to his writing. I will meditate on them, have them in mind, and find a visual and kinesthetic response.”

In a way, poetry of one kind or another has suffused all her work, whether she is responding to a line from William Butler Yeats or to the desert landscape of southern California. The lessons learned from her dreams four decades ago still spill over into the gently expressionist images from the waking hours of her present-day life.

Ann Landi

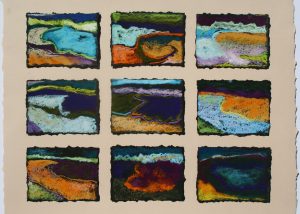

Top: Praise the Grace of Handel’s Water Music (2016, detail), pastel, acrylic, and gel medium on watercolor paper, 15.5 by 19 inches

This is a fascinating article on a very special artist. Jane is deeply honest, profound and inspiring.