The “genre,” if it is such these days, never really goes away

Landscape painting enjoys a long and honorable history in art, going as far back as ancient times, when the Greeks and Romans made frescoes of pleasant vistas and enchanting gardens. There have been periods when landscape has fared better than in others—in 17th-century Netherlands, for example, or in the great works of English painters like Constable and Turner, or in the classical landscapes of Poussin and Lorrain. The Impressionists moved the whole practice outdoors and introduced dazzling effects of broken color, and then Kandinsky and Mondrian ventured so close to total abstraction that they left themselves no option but to go all the way.

But in the last century or so landscape has languished as more cerebral or politically charged or high-tech approaches have seized the day. Nonetheless, in looking over the many artist-members of the site who are engaged in landscape in one form or another I would say a fascination with the natural world, and in ways we would still recognize as landscape, has never disappeared.

Herewith, a look at how seven Vasari21 artists tackle terra firma and beyond (I know there are others of you out there, and so this series will continue through the summer).

Barbara Kemp Cowlin

I came to landscape as a kind of default subject because I’m married to a commercial photographer who is passionate about landscape. As a family, we always took trips to places he was interested in shooting, and as he focused on his subjects I found myself taking an interest in ephemeral things. So I’ve developed my own eye for transient motifs.

First I used a digital camera, and now I use my iPhone. I point and shoot, looking for intersections, between hard surfaces and movement. I wind up taking dozens and dozens of shots and then back in the studio I find the ones that really capture my attention. I’ll piece them together, and as I work on the paintings I try to capture whatever caught my attention in the first place.

For the last seven years, I have focused on water and details of water. What’s different for me now is using acrylics—I never worry about making a mistake; I can sand back whatever doesn’t work for me. And because of all the different mediums available, there are so many ways of building up the surface. I’ve gotten to the point where I know what I’ll get, and I don’t have to think about that part. It’s like a dance between all the different possibilities for using paint.

Virginia Katz

Every artist wants to bring something new to the art of landscape. For me, it starts with a core connection. There are forces at work in the world that are bigger than I am, that are beyond imagining. I see landscape as a metaphor for the body. It is the place of our origins, and it is where we ultimately will return. We depend on it for sustenance, for knowledge, and for ideas.

Dudley Zopp

I don’t think about bringing something new to landscape painting. I’m only interested in understanding the natural world—and in order to do that, I draw it and paint it as honestly and unsentimentally as I can.

There are certain motifs that attract me. These generally turn out to be classic motifs that have endured over time, because humans seem to be attracted to or find peace in certain kinds of landscapes. Some examples: distant horizons, a path or waterway that leads into the distance or around a bend, tree lines, marshes, bogs, and low watery places.

I don’t often work plein air. I work more in the tradition of Chinese painters who spend long amounts of time in the landscape, absorbing what it has to say, and then create the paintings in the studio.

I try to understand how plants grow, and infuse my paintings with their life. The restoration of habitat where I live is a special interest, and offers endless subject matter. I vary that with self-directed residencies in other places—Newfoundland, Spain, Italy, Kentucky, and upcoming, the Southwest and the Carolina coast.

Color and space are important—to get these right, I have to use traditional techniques but I also try to arrive at interpretations or disjunctions that subvert the image.

I’m interested in the way we experience a scene visually—not everything can be in focus at once.

Lately I have come to realize that I also paint out of a sense of gratitude for living where I do, for the gifts of the natural world, and for being able to restore habitat to my part of the world.

Mitchell Johnson

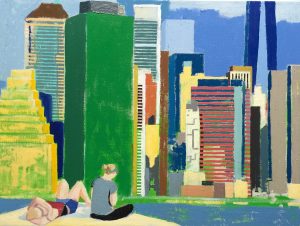

I met Wolf Kahn about 30 years ago, and he said to me: Somebody needs to save landscape painting—save it from shallowness, from Sunday painters and plein-air clubs. I totally agree with that.

I painted from life starting from when I was 19 or 20. It was a very straightforward way to understand how to see things, to learn how to build paintings and how colors behave.

I painted outside for about 10 years before I started making landscapes in the studio, and for a long time I have veered between abstraction and landscape. It’s all very intuitive, but they do inform each other. I work back and forth between small and large, abstract and representational. When I make paintings that are more abstract, viewers start to make the connection.

I’ve been working on a small painting of a view out of the New York Times building based on a drawing and a photo I took. It’s recognizable as New York, but it’s all about the shapes and the colors. And the way it’s built encourages people to think more about the differences between paintings and photos.

It’s very dangerous to make a landscape painting, but at the same time, it’s exciting.

Mariella Bisson

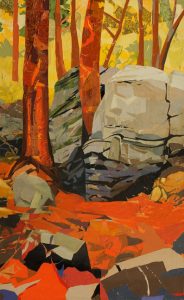

When I am in the landscape, outdoors, painting and drawing on site, I know what I’m looking at. I know geology, trees, and species of plants. I’m a bird watcher. I live in Woodstock, NY, and I have studied the archeological and geological history of the Hudson Valley. So I’m looking at things with a scientific eye as well as an artistic sensibility.

I’ve painted in the Southwest, but the landscape doesn’t speak to me. It’s too dry and powdery. The landscape has to be in your bones in such a way that you can really feel it.

What I bring to the genre that’s new has a lot to do with materials and techniques. I am looking for a rhythm that conveys the underlying message: How did this shape come to be this way? By using collage, I’m able to show a very dramatic and exciting edge—say, between rock and water. The way water flows, and it’s going to have an effect on the rocks, and the rocks on either side of the stream determine how deep the water is, and what colors we see. Collage allows me to carve shapes out of the paper, much the same way the water does to rock. I layer them on to the prepared canvas, so the planes replicate the planes of vision: what’s in front, what’s in the middle, and what’s deep background.

Mariella Bisson, Arc of Falling Water, Field Painting (2010), watercolor, gouache, and pencil on paper, 12 by 16 inches

Deonne Kahler

Everyone, amateur and pro alike, is making images these days and sharing them online. I’ve had iPhone photography juried into shows, so I’m not against it. The high-dynamic-range look that’s so popular now is technically beautiful, but it often feels soulless to me, almost as if it’s a stage set instead of a wild place, which flies in the face of what I’m trying to do with my work in the national parks.

My goal when I photograph landscape is to attempt to capture its soul. That’s obviously different with each national park, so I immerse myself in that place, view it from different angles, and try to convey its essence to the viewer. Every park has its own personality, and there’s so much soul that it’s almost overwhelming, at least to me. That’s what I’m trying to share.

I’m also obsessed with line and texture, more so than simply a beautiful vista. I’m not much of a fan of happy, sunshiny images, either—I’m drawn to darkness, shadow, and mystery. Which doesn’t come up in every park, but when I was in the California Redwoods a couple of years ago, I was in mystery heaven with all that gorgeous fog and shrouded landscape. It felt primeval, magical. One of my most popular images came from that experience.

I can’t top Ansel Adams’s exquisite images of Yosemite, and I don’t need to try. But what I can do, since there are more than 400 parks in the National Park Service system, is raise awareness for those places that are flying under the radar. I’ve always been a fan of the underdog, and I guess that applies to my photography as well. A person should experience Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon, because there’s nothing else like them on earth. But there are all these other beautiful, fascinating, or historic places you can visit. Every state in the U.S. has parks (and a few not in the U.S.) that are inspiring in their own ways, and my goal is to visit every single one and share them in photographs.

Lanny DeVuono

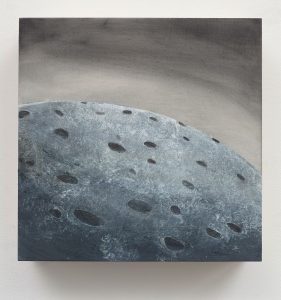

I don’t see myself as continuing the landscape tradition in the conventional sense, but I’m in dialogue with historical landscapes and have long used the landscape as a visual metaphor for human desires and aspirations.

What I’ve done for years is to use landscape to play with ideas of ownership. “OuterSpace,” my current body of work, uses nature imagery to raise questions about our interest in extraterrestrial travel and exploration, and to question the whole notion of colonial expansion.

With these drawings, I imagine an outer space like Theodorus DeBry must have imagined the Americas. Without having travelled to this continent himself, DeBry’s work and the work of his studio, were less incorrect than riddled with 16th-century European desires.

I conjure up the terrains of other planets with images of what is familiar, using pictures and ideas from our present-day earth and specifically the Southwestern US where I live, but last year I also travelled to the Sahara to research the barren beauty of sandy deserts.

Lanny DeVuono, Small Terraforming #8 (2017), graphite, gesso, wax, and gouache, 12 by 60 by 3 inches

Ann Landi

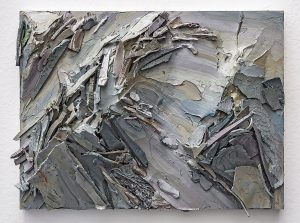

Top: Virginia Katz, Debris Field, detail ((2017), acrylic on panel, 16 by 12 by 4 inches

Hi Ann,

Thank you for including me & my landscape paintings in this article—your recognition of those of us working in this genre and giving it your consideration mean a lot to me and I’m sure to the other artists you highlighted in this article! Looking forward to Part 2 when you have a chance to get it written.

Fascinated with reading artists’ responses to landscape and their definition of what is landscape or place. And with their self Identified place within the genre of landscape image making.

I love the landscapes. As a photographer it’s also nice to see Deonne’s photography included in this post. Thanks.