Elisa D’Arrigo may be the only artist working in clay who can claim to have found early inspiration in “Dennis the Menace.” In one sequence from the hugely popular comic strip from the 1950s and ‘60s, Dennis’s parents are on vacation in Mexico and pay a visit to a potter working in his studio. While he manipulates the wheel with his feet, Dennis tickles his toes, and the potter laughs uncontrollably, producing an oddly shaped vessel. A woman enters the shop and immediately pronounces it “a masterpiece,” asking if it’s for sale.

“Seeing that cartoon made me want to do ceramics when I was seven years old,” recalls D’Arrigo, “though I had to wait for quite a few years to get there.”

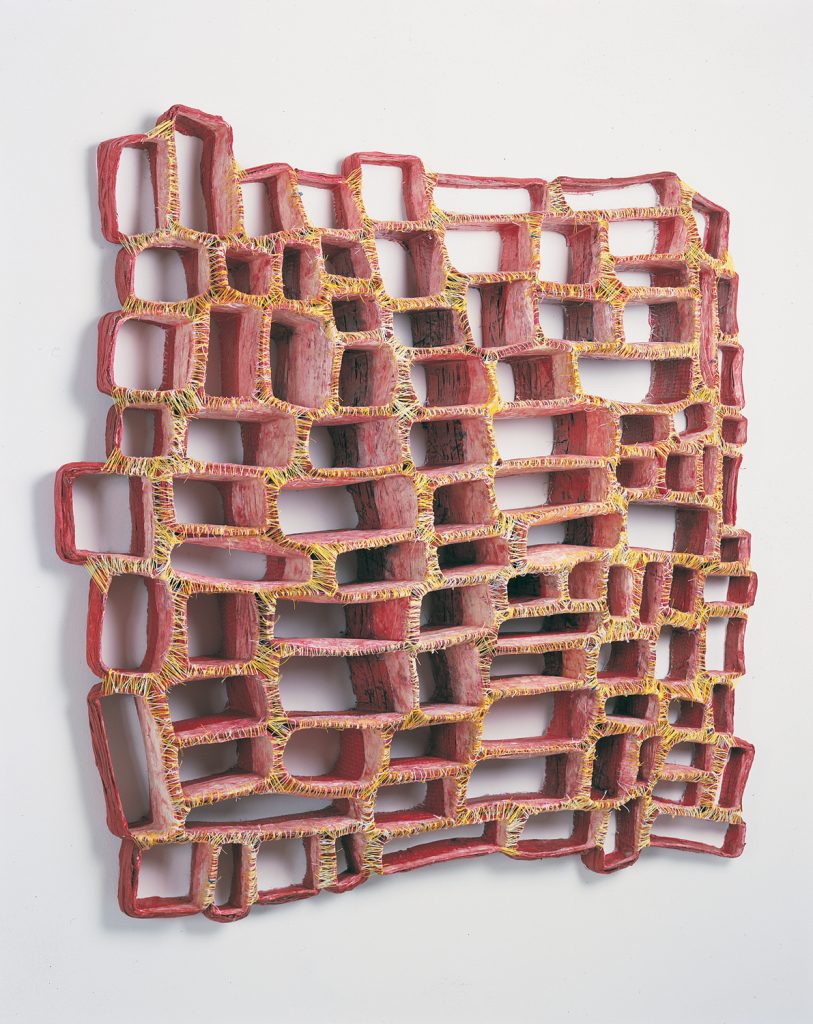

Cross Section #1 (2002), cloth, acrylic medium, acrylic paint, pigments, thread, 36 by 33 by 7 inches

Raised in the Bronx to parents of Sicilian origin, D’Arrigo was the first in her family to attend college, and when she arrived at the State University at New Paltz, NY, she got her first real exposure to working with clay. “It was just one of those things,” she says. “It felt like this powerful, magnetic attraction to the unbelievable malleability of something you could do in a second, like a conductor working on a score. There’s an incredible spontaneity, and you can achieve this very elaborate eccentric form.”

A trip to Mexico when she was 18 and a sophomore in college reinforced her desire to make ceramics. “I felt a kinship with both the work of contemporary Mexicans and with Pre-Columbian art—the graphic elements within a larger form, the massive amazing shapes of the buildings.”

Though throwing on the wheel—like the potter in the comics—was her first ambition, she soon discovered that neither the action nor the results were for her. “I was the worst in the class, and by the time I developed any proficiency at it, I realized the symmetry aspect was very uninteresting to me.”

For seven years after graduation, as a young artist in New York, D’Arrigo worked at hand-building ceramics, influenced by the sculptors and artistic currents around her—the new aesthetics embraced by Lynda Benglis, Eva Hesse, Claes Oldenburg, and others. “We were all coming up with our own weird inventive structures and mediums, coming up with new ideas of what a sculpture could be. There was something about sculpture—it’s not an illusion, it really exists in your space.” Vessels, in particular, exerted a strong spell. “What drew me to ceramics was the mystery of the vessel, the mystery of this contained space that you know from its exterior form,” she told Stephen Westfall for an essay written in 2007.

And then in 1981, she turned away from making ceramics, after working “maniacally” at it for seven years. “It became too familiar, and I segued out of it for 30 years.”

Though she was drawing and working in diverse materials—rope, wire, polystyrene, and encaustic—works from the 1980s still referenced hollowed-out forms and organic structures. She was fascinated also by a particular kind of cellular growth and repetition. As she wrote in an artist statement, “The repetition of forms certainly [does] allude to cellular structure but also to the accretion of objects/offerings that comprise shrines. The votive impulse has always felt very powerful to me (and is one I have been exposed to since early childhood) because it makes physical very intense feelings such as faith, hope, longing, and desire.”

By the late 1990s and early aughts, the artist had begun to realize many ideas in fabric, thread, and cloth—“sweaters and towels and things my family used over time” (she has a daughter, 22, and a son who is 19). The act of sewing also connected her to her past. “As a child, I was exposed to elaborate embroideries made by various female relatives, including my grandmother,” she writes on her website. “Seeing these textiles prompted a desire to draw with thread, thereby creating form and line by amassing stitches. I was captivated how a single gesture (a stitch), when repeated, can become something complex, elusive and rich with expressive nuance.”

By 2010, though, she was ready to get back to clay after a three-decade absence, and in the last six years has developed a vocabulary that has led critics to compare her to Ken Price and Kathy Butterly. Most of these sculptures mark a return to her fascination with the vessel—or, more precisely, the vase—but now there is a sense of inspired oddity. As critic John Yau noted in Hyperallgeric, “The rhythmic labor she employs to improvise upon a basic abstract form—a tube or hollow coil—has opened the artist up to a sense of the absurd, not to mention the quirky, the humorous, and the goofy.”

Like Price and Butterly, D’Arrigo is also a virtuoso with glazes, realizing surfaces that range from nubbly to smooth, adding areas that look almost as if someone had left delicate doodles, while textures can suggest a snake’s skin or a tree’s blistered bark. “I’m basically thinking like a painter, only with glazes,” D’Arrigo says. “I’m continually challenged not just by color and surface, but by how color makes a form change.”

The first show she had of ceramics in 2012 at Elizabeth Harris Gallery, her dealer for more than two decades, was all about vases. “I put flowers in the sculptures, and they brought out the humor in the work,” she recalls. “To me, there’s a subtle collaboration with the viewers. They have to use their imagination in deciding as to what these are and how to use them. That to me is very cool—it takes the work out of the realm of the precious and makes it much more approachable.”

Ann Landi

Top: Blue Sprawl 1 (2014), glazed ceramic, 5 by 10.5 by 6 inches

Ceramics courtesy of the artist and Elizabeth Harris Gallery. Arm’s Length, courtesy of the artist. Photos of ceramics: Jim Franco.

I would love to see this work in person. Too bad it is in NYC and I am in NM.

I love these! I also wish I could see them in person. So glad Arrigo went back to clay after all those years. A long break from practice can be frowned on but experience tells me it brings all sorts of new and wonderful things into play. I love Arrigo’s sense of play!