A make-believe show devoted to “hybrid objects,” neither paintings nor sculptures, but definitely here and now

By Robert Straight

Over a long period of time, there have been artists who haven’t accepted the traditional rectangular format for their paintings. Especially interesting is a group that that has used a hands-on approach to building and constructing a “painting.” These hybrid objects tread the line between painting and sculpture and are immersed in exploring and making an object. Oftentimes these works aren’t preconceived but made by the “seat of the pants.” The physical shape of the object is a byproduct of the execution, but all rely upon paint as an important part of the production.

Starting from scratch, each artist is in full control of every facet of the work, from the format to the application of paint and how it’s finished. These particular artists make perhaps the purest form of abstract art because there is in most cases no reference to the pictorial world. If there is an allusion to real objects or phenomena, as in works by Jean Arp and Elizabeth Murray, it is veiled so that it moves into a different arena altogether. Donald Martiny is at perhaps the farthest extreme of this group: he removes the substrate of the painting entirely, so that the paint itself hangs on the wall.

The artists included in the exhibition: Jean Arp, Paul Feeley, Ron Gorchov, Elizabeth Murray, Frank Stella, Cornelia Schulz, Helen O’Leary, Leslie Wayne, Donald Martiny, Otis Jones, and Robert Straight.

Jean Arp, who died at the age of 80 in 1966, is probably the grand-daddy of the shaped painting. He exhibited with the Blaue Reiter group in the early years of the last century, set up the Cologne Dada movement, and showed with the Surrealists between 1925 and 1931. His painted wood reliefs have a gentle whimsy about them and often make reference to shapes in Nature.

Paul Feeley’s work was always characterized by simple abstract forms, often in primary colors flatly applied to the surface. Though he came of age with the Abstract Expressionists (and died at the age of 56 in 1966), his approach was radically different from the gestural swagger of that movement. Donald Judd once explained how his paintings contained a “peculiar ornateness” that struck a balance between “being easily identified as ornate and Moorish and being thought something more new and interesting.”

Ron Gorchov, now in his late eighties, is another who early on eschewed the rectangular format. As his gallery, Cheim & Reid, notes, “Gorchov’s distinctive and assertive saddle-like stretchers were created in the late 1960s as an alternative to the pervasive Greenbergian formalism of the time….The stretchers offered a foil to his novel images, as yet seldom seen in contemporary painting.”

Elizabeth Murray (1940-2007) was and remains one of only a handful of women to be honored with a full-dress retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. As critic Roberta Smith remarked, she was a “painter who reshaped Modernist abstraction into a high-spirited, cartoon-based language of form whose subjects included domestic life, relationships and the nature of painting itself.”

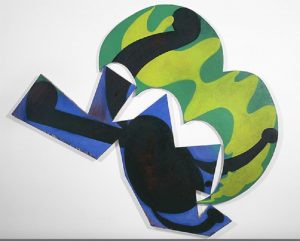

Frank Stella, who recently enjoyed a marathon retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, hit the ground running with shows at Leo Castelli’s gallery, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Guggenheim while still in his twenties. From his earliest series of notched black paintings to the present, he has relentlessly expanded the boundaries of painting as sculpture, or sculpture as painting. “All I want anyone to get out of my paintings, and all I ever get out of them, is the fact that you can see the whole idea without any confusion,” he once remarked. “What you see is what you see.” Shown here is one of his early collage paintings using felt.

Frank Stella, Targowica III (1973), felt and acrylic paint on Tre-wall cardboard, 122 by 96 by 8 inches

Early on, Cornelia Schulz mastered 3-D modeling techniques in steel and wood, and her altered rectangular shapes are hand-built wood supports, stretched with canvas. Using a knife, she “swirls paint into a complex brew of vibrant color, gestural oppositions and hair-raising improbabilities,” notes the bio from her gallery, Patricia Sweetow, in Oakland, CA. As San Francisco critic Kenneth Baker writes, “Schulz treated the outer contours of a painting as a troubled boundary between what she could control and the uncontrollable, between domains of intended meaning and of misreading and chance.”

Now in his 70s, Otis Jones builds up minimalist compositions through repeated layers of paint and then burnishes the surfaces to a luminous patina. Often referencing Tantric painting, his compositions explore relationships between shapes and ground, and in narrowing his focus to just a few elements, he achieves relationships of color and form that are brutal yet elegant, and richly meditative.

Born in Ireland, Helen O’Leary has said that her early experiences as a fatherless girl on a farm that went bankrupt in Ireland haunt her art practice to this day. “In the late nineties I started to disassemble painting, wanting to blow it apart and then re-settle it into a language that I could access,” she said in a recent interview. “I was interested in the notion of support and the veneer of stability, and the inter-changeability and whims of both.” Her works are constructed out of old paintings, and both the front and back are equally important. Elsewhere she noted, “I have disassembled the wooden structures of previous paintings—the stretchers, panels, and frames—and have cut them back to rudimentary hand-built slabs of wood, glued and patched together….”

Helen O’Leary, Home is a Foreign Country #18 (2018), polymer, pigment, and constructed wood, 73 by 63 by 15 inches

Leslie Wayne is best known for using paint as a physical material in its own right. She takes layers of oil paint, peeled off plastic surfaces, and then cuts and manipulates these to drape or wrap around or explode from the support. This work, One Big Love #74, she describes on her website as part of a series in which she sought to “escape the tyranny of the rectangle by painting only on shaped panels; and to listen to music while working (hence the title, ‘One Big Love,’ a song by Patty Griffin).”

Donald Martiny makes giant, disembodied brushstrokes, and in just the last eight years or so, has staked his claim on territory that’s unmistakably his: big, lush, exuberant sweeps of pigment that are neither paintings nor sculptures but hover in some space all their own. He starts with a small sketch on paper and then repaints that on to a sheet of plastic. When the paint is dry, if he is satisfied, he traces the form onto a piece of aluminum, and then cuts away the metal, leaving only the irregular shape of the painting. The aluminum backing and painted shape, joined together, then offer another kind of sketch, and he repeats the process on a much larger scale, using as many as 30 or 40 gallons of paint mixed with a polymer medium until it is about the consistency of Vaseline.

Robert Straight: Remembering my early days surfing, and loving the rounded contour of the rails of the surf board, I started making structures that reference the board. While I’ve worked with various canvas shapes, in the past this is a new adventure for me. The sculptural shapes become a way to get acquainted with the work before any paint is applied. The actual construction is a slow process involving wood, foam, canvas, and Hydrocal. So as I’m working, usually without, sketches, I’m considering both shape and form before the first paint application of paint.

Robert Straight recently retired after teaching for 37 years at the University of Delaware.He has exhibited in numerous shows nationwide and in 2011 created a temporary installation for the Philadelphia International Airport. Straight and his colleague Dennis Beach will be discussing their work at the opening of “From Color & Form to Expression & Response: Abstract Art at the University of Delaware. The opening reception is on September 20, from 5 to 7 p.m.

Top: An installation shot from Helen O’Leary’s recent solo exhibition at Lesley Heller Gallery, “Home Is a Foreign Country.”

Otis Jones

Loved cruising this show…

Well done, cool idea.

I enjoyed reading your curation and was introduced to some new artists(for me!). Huge fan of Helen O’Leary’s work. Thank you!