Some cynical, perplexed, and possibly spot-on observations

“Art star.” It’s a deplorable term, I know, but it’s out there as a label to describe those who have achieved a shining spot in the galaxy, commanding huge sums at auction, getting the nod from major critics, entering top-tier museum and private collections, and perhaps enjoying recognition in the glossies—publications like Vanity Fair or Vogue, which generally don’t pay much attention to artists unless money and glamour are involved.

Back in the late 1970s, when I was studying art history in grad school, a cluster of living art stars had already entered the canon. The art world was a much smaller place in those days, as crusty long-time observers repeatedly remind people. It was specific to New York and ruled by a handful of critics—Clement Greenberg (whose hegemony was fast waning) and his disciples, like Rosalind Krauss and Michael Fried. Barbara Rose and Hilton Kramer held forth at opposite poles of the spectrum, and the eminent art historian Leo Steinberg occasionally weighed in. By then, Donald Judd had also made his mark, both as an artist and art pundit writing regularly for Artforum, then the leading mouthpiece and arbiter of the contemporary scene.

I dutifully read criticism by all of them, for one seminar or another, and the artists they championed were already included in surveys of modern art (“postmodernism” had not yet entered the lexicon). You could tick them off easily on two hands: Frankenthaler, Stella, Motherwell, Johns, Rauschenberg, Noland, Oldenburg, Dine, Warhol, Kelly, Land Artists like De Maria and Smithson, and perhaps a few of the Minimalists). The central reasons they were held in high esteem were simple: they were all rule breakers, in one way or another, or they fit neatly into the Greenbergian formula of the forward march of Modernism. (The many excellent West Coast artists, with the exception of Richard Diebenkorn, at that point scarcely registered on anyone’s mattering map.)

I was not particularly hooked into the art-world zeitgeist during the ‘80s, having decided employment in the academic or museum worlds seemed beyond my grasp, and so I tested out my wings elsewhere as an editor and writer. But anyone who lived in New York in that decade was at least peripherally aware of the East Village scene, which included Eric Fischl and Julian Schnabel, and the members of the Pictures Generation—Barbara Kruger, David Salle, Cindy Sherman, John Baldessari, etc. etc. And poor doomed Jean-Michel Basquiat, whose trajectory through squalor and celebrity were ready-made for a biopic (which Schnabel would later realize to stunning effect.) That was the last time that I remember movements acquiring specific labels—NeoGeo, Neo-Expressionism, Appropriation Art (and of course Feminist Art had sounded a steady counter beat to all the macho antics since the ‘70s). It was a decade when, as Jed Perl noted a few years back, “the helium-balloon exuberance of… Warholism and Reaganomics joined forces to create the lunatic asylum the art world is today.”

By the time I got to ARTnews in 1994 and started seriously reporting and reviewing, the art world had exploded exponentially. There was now more interest on a global scale, and the canon expanded to include things like Queer Theory, video art, performance, the art of minorities, and contemporary art in once largely overlooked parts of the globe, like China and Africa. Money and marketing entered the equation in an ever more serious way, and the path to art stardom for jokesters like Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst was greased by sophisticated (and I would say cynical) manipulation and big bucks from big collectors. Still, the artists I wrote about and reviewed in my 20-year affiliation with the magazine—people like Tony Oursler, Nick Cave, Lynda Benglis, Nam June Paik, Nari Ward, William Eggleston, and many others—were in one way or another all rule breakers, bringing something new to their chosen disciplines or in some way breaking fresh ground entirely.

You might ask, nonetheless, what is the peculiar chemistry that catapults an artist into the pantheon? “Name” collectors, “power” curators, and rave reviews from major critics all help. And then there are the behind-the-scenes machinations that most of us will never hear about (I believe it was Perl who suggested that since many of the MoMA board members collected Cindy Sherman, it made perfect economic sense to give her a retrospective. What better way to protect your investment?)

Cindy Sherman’s retrospective probably got a boost from the MoMA board members who collected her work

All of which brings me to the Laura Owens retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, a two-floor exhibition I wandered through with increasingly dismayed eyes on my last trip to the East Coast in late January. A couple of weeks in advance of the opening, Peter Schjeldahl wrote an admiring profile of the artist in The New Yorker. I’d never heard of Laura Owens, which may demonstrate how appallingly out of the loop I am these days. But it made me curious enough to want to visit.

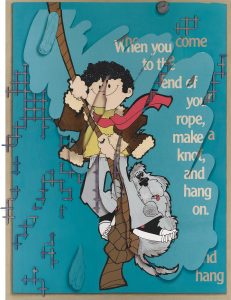

Owens is a 47-year-old painter based in Los Angeles. The subjects of her jumbo-sized canvases, some of them pushing 10 or 12 feet on the longest dimension, include a swarm of cartoony bees buzzing around a hump-shaped hive (top), real rubber tires affixed to a lavender and pink ground, a man whose head has become a lemonade juicer, and a white horse that seems lifted from a sappy calendar or a children’s book, barely constrained within its huge frame. But the real head-scratcher looked to be taken from sort of inspirational greeting card you might have gotten in the fifth grade from a well-intentioned aunt: it shows a boy and a dog dangling from a rope, accompanied by the words: “When you come to the end of your rope, you make a knot, and hang on.” Huh? What was the fuss about?

Laura Owens, detail of Untitled (2014), ink, silkscreen ink, vinyl paint, acrylic, oil, pastel, paper, wood, solvent transfers, stickers, handmade paper, thread, board, and glue on linen and polyester, five parts: 138 1/8 by 106 ½ by 2 5/8 inches

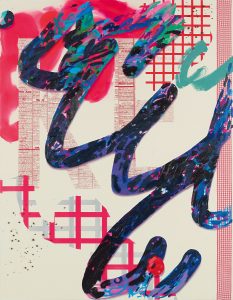

To be honest I liked many of the paintings that combined mostly abstract elements in ways that vibrated with graphic and coloristic exuberance: big fields of writhing loops and squiggles, set against grids, printed wallpaper, and swaths of gingham. But I wondered at the point of riffing on a Toulouse-Lautrec painting of two prostitutes in bed, which in turn, I later learned, was borrowed from a contemporary fin-de-siècle cartoon (maybe this is appropriation of appropriation art, or post-appropriation art). And I failed to see the wit or innovation of basing five free-standing panels on a story written by the artist’s young son, which are readable only when the viewer stands in the right place.

Laura Owens, Untitled (2012), acrylic, oil, vinyl paint, resin, pumice, and fabric on canvas, 108 by 84 inches

So when I got home I turned to a few critics, who were almost unanimous in their praise of the show. In a lengthy paean in The New York Review of Books, David Salle applauded Owens’s “continuous run of invention and forward-thinking bravado” and her “superior pictorial instincts,” calling the show “the apotheosis of painting in the digital age.” Roberta Smith in The New York Times called it “a smart, beautiful show [that] bodes well for painting.” And Phyllis Tuchman in ARTnews online hailed the retrospective as “a game changer.”

The lone dissenting voice among the reviews I tracked down was John Yau’s in Hyperallergic, who remarked: “What is striking about the works in this exhibition is how completely sterile, mainstream, and middlebrow they feel, with just enough insider info to flatter the viewer who knows something about Roland Barthes.”

Does the general consensus make Owens an “art star”? Yau none-too-happily concedes this may be so: “Critics, curators, and collectors concur. This exhibition is the official anointing of an American genius.”

And yet anyone who has paid attention to the art world of the past 20 to 30 years knows that many have been anointed and few have had real staying power, not because the quality of their work has declined (I’m sure those who made waves years ago are still working, perhaps at the top of their game) but because the art audience is fickle: collectors move on, curators change venues, the press requires fresh talent to celebrate or eviscerate.

After seeing and reading about a show like the Owens retrospective, I’m glad I’m out here in the boonies, patiently cultivating my own garden of artist members, who continually surprise me with the strength of their convictions and the ingenuity of their highly personal visions. And almost never, ever make me gag.

Top: Laura Owens, Untitled (1998), acrylic on canvas, 66 by 72 inches

Ann,

Thanks so much for this. I was searching for someone who had a similar opinion of Owens’ work which after looking and researching and reading, still left me scratching my head. I appreciate your honesty — refreshing as always.

Best,

Tracy

Thank you Ann Landi. I seem to be finding it more and more difficult these days to find what feels to be a voice of reason and when I occasionally stumble upon one I find myself celebrating. Having just finished your piece I am indeed currently in the midst if one of those celebrations.

I have lost patience with lazy art, which seems to be vogue these days. Back in the sixties when Warhol did it, it was interesting, at least for a few weeks. Today, fifty years later it is amazing that so many who should know better are so unable to jump from a tired old ship barely afloat in a sea of pablum and humdrumery. Thank you for seeing past the hype and having the nerve to point out the emperor isn’t wearing any clothes!

Thank you Ann for being a well-reasoned, experienced voice for sanity in what can sometimes seem like a nutty art world. I did very much like the Laura Owens ‘gingham/collage’ pink-red works in her show but beyond that I was able to apply my well-toned head-scratching and eye-glazing skills. Still it’s fun to see someone being anointed an art star — I’m pretty sure the whole thing is one postmodern gag a few insiders play just to ensure no one ever thinks they ‘get’ contemporary art or could convincingly explain what makes a work good or better. What fun!

Thank you Ann for another Editor’s note with great spot-on observations.

The first time I saw Laura Owens’s work was at the Phoenix Art Museum & I was completely unimpressed to say the least.

The really creepy thing is that after reading so many glowing reviews I began doubting my own opinion. I proceeded to buy the Laura Owens catalog published by the Whitney to figure out what was wrong with me!!! I was working hard to convince myself that I, too, thought her work was brilliant.

Thanks to your observations I can drop back to thoroughly disliking her work (except for the abstracts). But it’s a personal example of being swayed by the media. I’m horrified at myself—and glad to have an clear cut example of how easily my opinion can be swayed, so that the next time this happens, I’ll remain open minded but ultimately trust my own opinion. Maybe you should add shrink to your job description.

Dear Ann

I was thoroughly baffled by Laura Owens work as inclusion in any museum. But then I was more put-off by the Whitney biennial’s selection of art – so inexplicable that they

were forced to hire designated persons to explain certain works to viewers. A

disappointing first.

They should re-think their curatorial staff- hope this is not too strong a comment but this conversation struck a chord with me.

Dear Ann

I was thoroughly baffled by Laura Owens work as inclusion in any museum. But then I was more put-off by the Whitney biennial’s selection of art – so inexplicable that they actually hired persons that were designated to the works that were baffling to actually explain works to small audiences

A disappointing first.

They should re-think their curatorial staff- hope this is not too strong a comment but this conversation struck a chord with me.

Yay!

Amen!

Ann,

I love clarity.

Thanks for this,

Diane Sanborn

We’re glad you’re out in the boonies cultivating a saner art world, too. Thanks, Ann!

I am an artist. This is my review that i published on facebook and my blog after seeing this dreadful show. I got attacked by the art world movers and shakers so much so that I unfriended one, and blocked others. I know all of the people you mentioned as I came of age in the early art world of the 70’s. I thought I was crazy, the only one who hated this show so thanks for your response don’t feel so crazy any more.

Laura Owens the Whitney Museum

This large incompressible retrospective of the California artist Laura Owens, now spewing out all over the 5th floor of the Whitney might very well be the worst exhibition I have ever seen in a museum or for that matter anywhere on this planet. Harsh words I know, but let me continue before I’m condemned for refusing to follow the leader and jump up and down for nothingness.

Comprised of campy ugly badly painted canvases many using kitschy imagery culled and pulled from our popular culture along with nods to paint by number works , untaught and naive art, children’s art and drawings that you might find scribbled in toilets along with art that can be found in the $2.00 bin at your local thrift shop or in the street thrown away with the trash. Actually anything you would find and see in the above places is much better than anything to be found in this pompous and pretentious ragged ugly show.

I like camp and bad painting as much as the next one, but these are so jaw dropping bad that their meager gifts for amusing is very minor to say the least. At first I thought this show was a joke something made up by a New York Times Critic and the curators to get back at us, but unfortunately not. This show is real folks and what I can’t understand is how and why this minor in a big way artist got this ticket to ride.

Owens covers the spectrum of painting: there’s abstraction, tearful representation, lousy landscape painting, weak political statements and on and on. There is even a grotesque and silly installation of Ikea like bedroom furniture in passive pastel colors of brown, orange and green topped off by large stupid paintings of bee hives done in matching colors with the little insects buzzing around which would make a perfect gift for the hipster in your life.

Probably the most offensive works, (and believe me there was plenty to pick from) were the many small square paintings that hovered over our heads and were hung close to the ceilings that were dreadfully painted, dreary and included some with movable parts. All of the works offered seemed to me to have none or very little interest in paint handling, color, texture or imagery, they simply laid there like a badly cooked dinner sitting in your stomach that keeps repeating itself throughout the night as you try to sleep, and nothing in the medicine cabinet is going to help it go away.

Most of the works looked rushed and haphazard, lazily painted without any feelings not only for the subjects but also for the materials used. She is another privileged artist (check out the protests that were held here on her opening by working class members of the neighborhood of Boyle Heights in L.A. who are largely Hispanic and who are upset with the gentrification of their hood that is being pushed by Owens and her other privileged friends and artists) with nowhere to go but down which hopefully will be sooner than later.

Reasons (excuses) can and have been made for these works and many have been called up and heard using her education, her background, her sense of place and her readiness to call up previous and better artists for her inspiration along with her superficial use of what is fashionable and trendy, just check out the 500pd catalog that will bring back memories of a high school yearbook or as one critic called it “like a thick issue of Vogue.”

Should we take this as a compliment, I think not. The whole exhibition is like a thick issue of Vogue, but without the pretty models. Why is this kind of painting being celebrated and held up as important work? This is thin and unimportant painting and an insult to serious painters everywhere. If you need a blast of fresh air after this disaster of a show you can head outside to one of the terraces with views that easily rival this show for intensity and beauty and after you clean out your eyes and mind head on up to the 7th floor to check out a lavish spread of many splendid works from their permanent collection that will make your spending $25.00 admission fee feel worthwhile and help take the bad taste out of your mouth for what the Whitney has made us swallow. The worst exhibition of 2017.

I saw the exhibition by accident. Didn’t know I was in the presence of a star. I didn’t give it much of a chance, since I saw the installation which required specific viewpoints first, and then I have to say, lost interest and neglected the rest. There were so many excellent opportunities during my two week visit back in the city, I didn’t give her work much thought. Maybe I should have tried to figure out why.

So Ann, thank you for your thoughts and the depth of your experience looking at art and your curiosity about the strange phenomena in the art world.

A fine piece of writing and strong clear point of view. And I also enjoyed reading through the comments. Your piece exposes for me several difficult strands of an art world that is so dissociated from the real deal: art as commodity; the players who determine in specious deals who can become a player; and what happened to art criticism. And about audience fickleness I would love a conversation about cultural differences – are Americans uniquely fickle?