It’s hard to imagine an artist more authentically “Western” than Tracy Linder. She grew up on a family farm not far from where she lives now in Billings, Montana. As a girl, she participated in all aspects of life lived close to the land—harvesting, irrigating, and helping with the animals. She raised and trained steers for the 4-H Club, and went to small country schools. Every year she still works the harvest season, most recently driving combines for her neighbors. She now lives on 20 acres of pastureland with three horses, one dog, and “an unknown number of cats.” And her husband is the sheriff of Yellowstone County.

In her art, she says, “I’m always looking at resilience, vulnerability, and survival, taking in different aspects of animals and machines and seeing what the connections are.”

“Beets” (2004-2007), animal collagen, artificial sinew, organic matter, polyester resin, series of 32

Though her works often celebrate the nobility of the rural life and the natural cycles of the seasons, there’s nary a trace of sentiment in her approach. Linder works in very up-to-date idioms: her projects are mostly installation-based, making smart use of materials like polyester resin and fiberglass (along with traditional materials like bronze and oddball elements like dyed grass, leather, and animal collagen). For optimum impact, she relies on dramatic lighting, life-size scale, and Minimalist strategies of repetition. Savvy viewers will see in her sculptures lessons learned from some of the iconic figures of contemporary art: Eva Hesse, Joseph Beuys, and Rachel Whiteread.

But to find her own voice took some time. “I always had a proclivity for being creative,” she says. “Working on a farm necessitates creativity. If you’re out in a field and something goes wrong, you have to figure out how to make it right.”

In school she “didn’t like subjects where there was a right answer. I gravitated toward the arts because there’s no right answer.” As an undergraduate at Montana State in Billings, she started out as an accounting major, but two years into college realized she was no accountant. “I craved taking an art class, just for fun.” A counselor gave her a battery of psychological tests and told her she should be a park ranger. “I didn’t know that you could be an artist,” she says. “I didn’t know what that looked like.” Nonetheless, at Billings she gained a strong foundation in drawing skills and technical expertise—”mixing plaster, sculpting the model”—and then went on to earn master’s degrees in more “idea-oriented” programs at Eastern Illinois University in Charleston and the University of Colorado at Boulder.

Growing up in the West, Linder was mostly exposed to cowboy and wildlife artists. “I was a frustrated farm girl, a ranch girl, trying to figure out my life experiences and what’s important to me,” she says. “How do I find a contemporary voice in the life I live every day? I’ve spent the last 25 years continuing that conversation.”

Her first job was teaching part time in Billings for six years—beginning drawing, sculpture, color and design, and advanced-level photography. “From the MFA forward for two years, I put everything into the work. What I needed to do was pare down and go deeper, refine my aesthetic. I painted on large photographs, blowing up images to as much as eight feet, transferring the images on to collagen.”

Her teaching career ended in 1997 because of budget cuts at the university. “I wasn’t making much money, I was married, the commuting costs were high,” she says. “My husband and I had lots of conversations and how this was going to be. He supported my staying home and being a full-time artist.”

Linder’s first major project, “Conversations with the Land,” announced the arrival of a fully mature artist. The installation “presents up to seven large bolts of animal collagen that hang from rods like curtains or drying animal hides,” writes curator Lisa Hatchadoorian. “On these wrinkled, golden and translucent surfaces are ghostly images from farm life that hint at loss and memory.” These included tractors, her father, the sugar-beet harvest, and other evocations of her experiences.

“Wings” (2007), polyester resin, fiberglass, pigment, light, 100 wings, dimensions variable, installation view

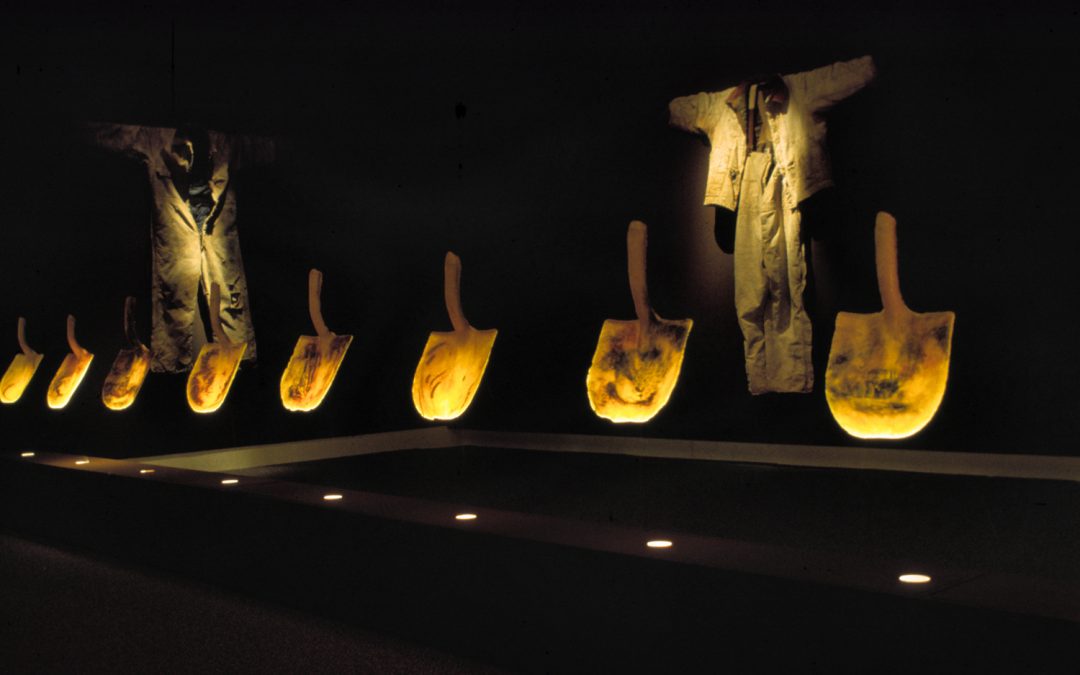

Her next installation, “Shovels” (1999-2000), consisted of 30 shovels made from beeswax, again embedded with photographs—of working farms, crops, animals and bones. Behind these Linder hung the overalls of local family farmers. “They looked kind of crucifix-like,” she noted, and reinforced that sense of a spiritual experience she hoped the work would convey.

Throughout Linder’s impressive opus of the last two decades runs an almost surrealist, haunted quality, animated by allusions to the grubbier aspects of the natural world and our place in it. “Tractor Hides” (1997-99), though plainly modeled from actual tire treads, resemble gigantic blow-ups of the larval stages of insect life. “Beets” (2004-2007), with tendrils of artificial sinew dangling from hairy bulbous shapes, conjures up the messy and mysterious tangle of life beneath the earth. An installation of farmers’ and ranchers’ gloves (2006-2007), cast from the real thing, protrude from the wall, gesturing in a way that is every bit as disquieting as Cocteau’s wall sconces from “Beauty and the Beast.” Linder herself notes, “You can feel the presence of the person who wore it. I put on each glove to feel where its memory was, and used a resin process to get them to hold that gesture.”

Perhaps the most disturbing of the artist’s series is “Pound of Flesh” (2016), which uses leather to simulate the skin of dead calves, and is a recognition of one of the more gruesome but practical aspects of rural life. “When a cow loses a calf early on, ranchers skin it and tie the hide on to a new calf, so that the cow knows the smell of that old calf and will nurse it.” She shows the sculptures on the floor to boost the empathy level. “When I put them on the wall, the perspective is lost. When the works are on the floor, they look as though discarded.” But, as she wryly notes, “It’s been a slow go getting these exhibited.”

Yet other of her installations are pure poetry. One hundred lifelike bird wings, cast from fiberglass and polyester resin, are attached to a wall and lit from below, throwing steep shadows onto the surface behind them. Gigantic stalks of wheat seven feet tall, shooting off spikes of dried grasses, hang from the ceiling, responding to whatever air currents disturb their majestic shapes.

Tracy Linder at her TedX talk in Billings, MT

Underlying virtually all Linder’s projects lies an ecological consciousness that most of us share, even if it’s not our immediate reality. The loss of the family farm to agribusiness. The brutal realities of animals raised on an assembly line. The devastation of the landscape because of climate change and the erosion of environmental controls. And the absence of engagement between what once lived and what now sits on our plate.

“I worry about that disconnect,” Linder says. “That connection to the land and the knowledge that it’s the environment of some living thing. We have so many mental-health problems, maybe because people don’t have the opportunity to experience realities that go beyond our immediate circumstances.”

In Linder’s works, we are reminded of both the strange beauty and the endangered dignity that are part and parcel of both our agrarian past and our dystopian present.

Ann Landi

Top: Tracy Linder, “Shovels” (1999-2000), installation view

Ann, Thanks so much for your eloquence and real interest in the work. I am very touched by your earnestness in helping artists everyday.

Also, a quick note to those who might want to look at my work further, my website is http://www.tracylinder.com . I don’t always come up in google so, just in case!

Thank you!!!

Wow I am so blown away. Beautiful article and amazing works of art.

Tracy – I so admire your work and your ethos – The life you have made.

And Ann this is written beautifully- with a quality similar to Tracys work.