As a kid growing up in Chicago, Tm Gratkowski believed he was destined to become a hockey player. “I was on skates at age three and playing hockey by the time I was five,” he says. “We grew up on the lake, and I would put on my skates at the house and walk down to the lake. I did it religiously, nonstop. And that pursuit and discipline carried over into art.”

An interest in making art didn’t kick in till much later, but his household was a lively one where all kinds of pursuits were encouraged. His father worked as an electrical engineer and played the drums; his mother took art classes and played the piano; and his grandparents, who frequently took him to museums, delighted in playing games—board games, puzzles, word games. At one point, his grandmother noticed Gratkowski playing with Popsicle sticks and commented, “Oh, you’re making art!” That marked the first time he realized he could “manipulate materials and get people to respond.”

But it was not until he embarked on an eclectic college career that included studies at the Art Institute, the University of Wisconsin, and a semester abroad in Vienna that he settled on the idea of becoming either an artist or an architect. “As crazy as it may have appeared at the time, in the long run going to many different schools gave me an ability to move around and experience different things in different place,” he says. “Even in my art career now, I can write, I can design and build a house. I can freely jump around without skipping a heartbeat. It probably wouldn’t be that difficult for me to write music.”

When it came time to consider graduate study, Gratkowski decided on the Southern California Institute of Architecture “because it was an art school for architects.” Soon after earning his master’s degree, he went to work for Frank Gehry’s firm, a business where many of the other architects were also involved in the visual arts, making paintings or photographs on the side. The artist got to know Gehry because he was wearing a Black Hawks hat in the office. “Frank won’t talk architecture or design with you, but he will talk hockey.” He doesn’t credit Gehry as a direct influence on his work, but the experience “pulled out of me that it was important to pursue a creative discipline. I got interested in architecture as another way of pursuing sculpture.”

Gratkowski has worked as an architect on and off, developing his own interests in collage on the side. One of his more rewarding commissions was a competition he won to build the Sun Pavilion for the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City, MO, in collaboration with with his long-time friend Tom Proebstle, the design director and founder of the architectural firm Generator Studio. “The whole thing, as it appears on the front lawn, looks more like a sculpture in many ways,” he remarks. Positioned next to a gently swelling Henry Moore, the structure has an attentive, bristling quality, and Gratkowski says it was a project that coalesced “in the most perfect way. It was nice to see two of my worlds coming together.”

Working with solid materials may have paid the bills, but Gratkowski’s big love has always been paper. “When I was taking art classes as an undergraduate, I got bored with traditional materials. I started to add a lot of things to the drawings and paintings, adding more and more paper, collaging within a painting or drawing.” A few years after graduate school, “things slowly became more about paper.” He did a series of black-and-white collages, making a group of works on lunch bags, and came to the realization that what looked great at 9.5 by 5 inches could be blown up to a four- by six-foot collage on butcher’s paper. That was in 1996 and he describes it as “the apex of the Aha! moment, when you find that thing you’d been searching for. The architectural folly for the Nelson-Atkins was even based on collage and combining things that look like they don’t necessarily belong together.”

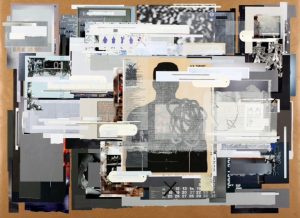

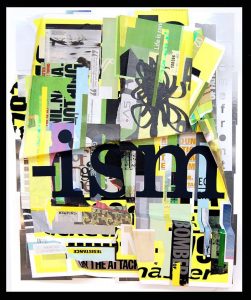

For the last two decades, Gratkowski has been finding ways to update and exploit ever more ingenious and timely spins on a century-old aesthetic that was born when Picasso first glued a printed swatch of chair caning to one of his paintings. His collages can be monumental or intimate, flat or protruding from the wall, and almost always entail the use of printed words or phrases. “The artist combines a pointed commentary on contemporary life…with a visual pattern that repeats and disrupts,” noted one reviewer of his 2016 show at Walter Maciel Gallery in Los Angeles. “Dimensional collage encourages viewers to ‘dig into’ the painting’s folds of paper that extend outward in stylized swirls and curls from the surface.”

There is often a subtext of social commentary in the works, as in a piece that exhorts “Do Not Stay Quiet” or the long shimmering expanse of cut papers on a silver ground (at the top of this post) that says “physical structures that constitute boundaries {skin} aren’t necessary to identify us.”

“I’m always in support of the underdog, whether or not I consider myself an underdog,” he says. “I felt that most issues like gun control, homelessness, capital punishment, sex, religion, and so on kept reappearing throughout history, usually unresolved. So I thought I would focus on creating artwork that would try to be at the center of these conversations or issues. Not to make a hard-line statement for or against but more to offer a fair representation, where viewers could become aware of all the issues and become better informed, either solidifying their original opinions or better yet slightly changing them through a broader awareness.”

Gratkowski may be the first, to the best of my knowledge, to translate collage successfully into sculpture. “I never paid that much attention to sculpture,” he admits, “and I was looking for something else to do. What could I combine with paper that would make it more permanent? Why not try cement or concrete? I made a very small mold and mixed together concrete and paper, poured it in, closed it up, and when I broke out the mold I started pulling paper out of the concrete.”

That was five years ago, and he’s made about 50 three-dimensional works since. “It’s almost as if the concrete is holding onto the paper and the paper is trying to free itself from the solid piece of concrete,” he told another reporter. “The two materials need each other to create these new sculptural forms.”

It may not be too much of a stretch to see a little Gehry influence in the sculptures: Gratkowski takes flimsy scraps and marries them with a heavy building material; Gehry bends the surfaces of his buildings to make them appear as malleable as paper, thereby lending them a sculptural presence. But an abiding interest in the power of making of things and the presence of words goes back even further—to the Popsicle sticks and word games of his childhood.

Ann Landi

Top: Polyphony (2016), paper and paper foil, 78 by 264 inches

Wonderful and informative article on Tm’s work. i hope the collectors take notice.