Donald Martiny’s earliest memory of being mesmerized by paint comes from kindergarten, when he lived in Schenectady, NY, and had “a teacher who was really stingy about art supplies,” he recalls. “She would give us only two jars of poster paint, and I remember being entranced looking into those color pots. The first thing I did was drop orange paint into green paint. I think it was at that time that I knew I wanted to do something with color and movement.”

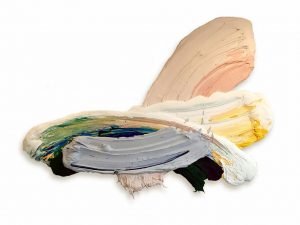

The moment may have been a precociously prescient one, but it would be decades before Martiny got to the point where he felt like he “owned” his work. In just the last seven years or so, the artist has staked his claim on territory that’s unmistakably his: big, lush, exuberant sweeps of pigment that are neither paintings nor sculptures but hover in some space all their own. The success of this new language has led to numerous gallery shows on the East and West Coasts, along with a challenging commission for the ground floor of the new World Trade Center.

When he was eight, Martiny’s family moved to Kalamazoo, MI, and at around the age of fourteen he “jumped on a bus and took it to Chicago to the Art Institute,” he says. “I just knew that I wanted to see real art. There was a show of Rembrandt, and that really impressed me.” Throughout high school he was taking college-level classes in art history and fine arts; in the summer, he always found art-related jobs: silk-screening, working as a woodcarver, and doing stone cutting.

Martiny spent only a summer at the University of Kansas, but the experience marked the first time he could regularly visit art museums, like the Nelson Atkins in Kansas City and the Spencer Museum of Art on campus. A couple of encounters at that time left a lasting impression. One was with a Lynda Benglis poured piece, called Phantom, which he saw as “freeing paint from the wall.” Another was his attempt to “deconstruct” a de Kooning. Like many who are learning their craft, the artist made copies of old masters like Vermeer and Ingres, and in 1972 he tackled de Kooning’s Woman IV from the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City. What he thought was going to be an easy exercise turned out to be the hardest of all. “It was more like building something,” he has said, “because every gesture in the painting does something different. I realized that the architecture of the brushstrokes was as important to the painting as other elements, like color and drawing.”

Martiny eventually enrolled at Hope College in Holland, MI, but didn’t last long there, since he “knew New York was the place to be”—that’s where all the artists he admired were living. After landing in the city, in 19tk, took a job at the Doubleday bookstore on Fifth Avenue and 57th Street, buying volumes on art for the store. Artists represented by the 57th Street galleries, which made up the hub of the New York art world at the time, would drop by—David Hockney, Philip Pearlstein, Ellsworth Kelly—and eventually dealer Allan Frumkin, who took note of Martiny’s interest in art and asked him to come work at his gallery around the corner.

All through those early years in the city, he took classes at New York University, the School of Visual Arts, and the Art Students League, where he became the class monitor for Robert Beverly Hale, then the dean of academic anatomical drawing and painting. Eventually he became adept at illustration and when he left Frumkin took a job at a mapmaking place in the advertising department. “I was an art director of many years, slowly working my way up to being a creative director,” he recalls. “I got into it because I loved working with paper, with color, coming up with ideas.”

Martiny held positions as a creative director for ad agencies for more than 25 years, until 2010 when he was able to turn to painting full time. His works are largely realized on the floor. He starts with a small sketch on paper and then repaints that on to a sheet of plastic. When the paint is dry, if he is satisfied, he traces the form onto a piece of aluminum, and then cuts away the metal, leaving only the irregular shape of the painting. The aluminum backing and painted shape, joined together, then offer another kind of sketch, and he repeats the process on a much larger scale, using as many as 30 or 40 gallons of paint mixed with a polymer medium until it is about the consistency of Vaseline. Sometimes he uses a wide brush or sponges to manipulate the pigment, but more and more of late his hands get into the act too. When he judges the work to be complete, it goes from the plastic to another aluminum backing that can then be affixed to the wall.

For the first couple of years into making the giant brushstroke paintings, Martiny worked with the most basic colors—blue, red, green, yellow, or orange. They still inform his palette, but of late he’s also been experimenting with “off” colors or adding other hues to the mix. “By changing the values or exploring the addition of other colors, it’s become easier to see the architecture of the gesture,” he says. “I like the process to be visible.”

In 2015 Martiny received a commission from the Durst Organization to create two monumental paintings that are permanently installed in the lobby of One World Trade Center in New York City. The artist moved his studio into the lobby and had two months to make the 12- by 15-foot paintings. “Working on site was terrific because I was able to respond directly to the changing light, movement and space of the building,” he told Professional Artist magazine. “That said, there was no room for failure and I had a tight deadline. For me, the process of painting requires a tremendous amount of concentration and focus. Because of that I have never painted in front of anyone before. The lobby of One World Trade Center gets something close to 25,000 visitors a day.” In spite of the pressure, Martiny says, the WTC commission was ultimately “a tremendously positive experience from beginning to end.”

About six years ago, Martiny and his wife, artist Celia Johnson, moved from Philadelphia to a rural area outside Chapel Hill, NC, and soon thereafter he was offered a solo show at a gallery in Durham. “I just knew it was time,” he says. “My studio is in the woods near a pond and has glass on two sides. The constant movement of light and nature thrill and inspire me. The other day a family of deer lingered outside my studio window, and I watched as a young faun nursed from its mother. Although I certainly miss the community—the art openings, lectures, and museums—I feel fortunate to be here.”

Ann Landi

Top: Zhang-Zhung (Lonely Journey), 2016, 47 by 88 inches

This is an inspiring story. I’ve seen Don’s work at Tiger Strikes Astroid in Philly and it beautiful in person. Continued good luck to Don as he keeps going.

I am moved to see this work in person! Stunning!