Yes, I have been living under a rock. And I’m proud of it.

When I read, a few days ago, that Helen Marten had been named the 2016 winner of the Turner Prize, Britain’s biggest accolade in contemporary art, I drew a big fat blank. “Helen who?” was my response. And immediately I set to Googling, and my heart sank. Oh, no, thought I. Please, not more of this.

Helen Marten makes agglomerations, often room-sized, of flotsam and jetsam (and I’m citing the reviewers’ inventories), like shards of glass on a plank, tote bags filled with personal items, a half-drunk Starbucks cup of iced coffee, fast-food boxes, cartoon tabby cats, screen prints on leather….well, you get the idea. But let me quote at length about one particular installation: “Bluebutter Idles, a recent work acquired by the Arts Council for almost £53,000 last year, consists of a steel trough supporting bespoke objects made from stitched and stuffed fabrics, clay, bronze, welded steel and woven straw,” writes Alastair Sooke, art critic for the Telegraph. “A diminutive, strangely hairy figurine lies slumped across the top of the trough, supporting a blue phallus and a shell. A stalk of corn, meanwhile, stands erect, providing a delicate flourish.”

For the most part, the art world has adored her. In 2010, at the ripe old age of 25, she had her first solo show at T293 Gallery in Naples, one of four blue-chip galleries that currently represent her work. Four years later, she had shows at key institutions like the Palais de Tokyo in Paris and London’s Chisenhale Gallery. In 2013 and again in 2014, she was part of the 55th and 56th Venice Biennales. And in addition to the Turner, a few months ago she scooped up the Hepworth Prize for Sculpture.

“So, unless you’ve been living under a rock,” opined one critic, “You’re bound to have either encountered Marten’s work in these past months or at least seen a string of coverage about it.”

I freely confess: I have been living under a rock.

When I went to read other reviews of her work, I encountered only breathless encomiums: “Marten bestows a sense of ordered, poetic, cleanliness on her installation that sets the work apart from that of other artists” and “Marten’s work in general is a bit like good hip-hop: ready to twist and wrench and squeeze every single bit of its semantic material, milking it for rhythmic flow—and meaning” and “her way of thinking, with its word salads and trap-door metaphors, is dangerously infectious.” Comparisons with Lewis Carroll, John Ashberry, and James Joyce also abound in both the art and mainstream press.

Installation view of the 2013-2015 traveling solo exhibition “Isa Genzken: Retrospective” at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago

In all my Internet trolling, I discovered one lone dissenting voice. Michael Gove, a conservative member of Parliament (and therefore perhaps no art expert), called it “modish crap” that exemplified “the tragic emptiness of now.”

I am judging only from online images, and so perhaps I cannot make a fair assessment of the experience of Marten’s work, but it looks to me like part of a trend I call “The New Ugly” or maybe “The New Bafflement,” to be more accurate. Artists who fall under this rubric include Isa Gentzken, Steven Claydon, and Rachel Harrison. It seems to work this way: “Let’s put this next to this and then stick in this and maybe these things too and see if it flies.” You can use just about anything you want—candy wrappers, mannequins, fire hydrants, screen prints, kitschy ceramics, your underwear, your boyfriend’s underwear, your cat’s litter box, and on and on. As long as the stuff is artfully put together and makes sense in the artist’s mind, it should also convey something to the viewer. And we are just plain stupid if we don’t get it.

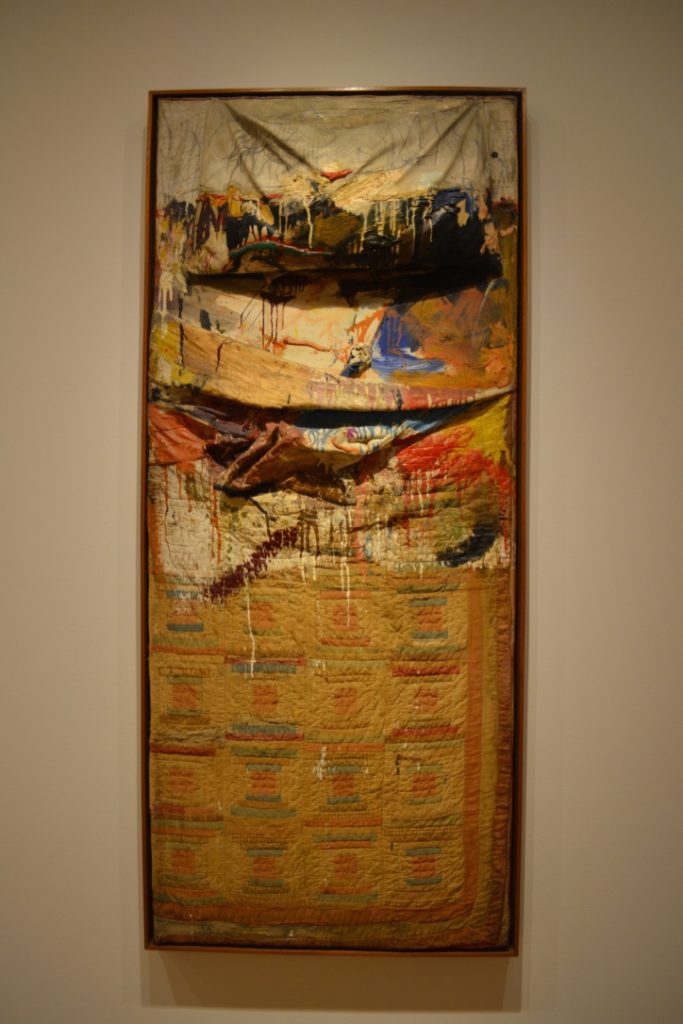

This is a way of making art that has a venerable history, at least as far back as the Surrealists, when André Breton announced the movement’s objectives to be “as beautiful as the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table.” More recently Robert Rauschenberg became the American master, and one of the progenitors, of this aesthetic, producing “Combines” that married the disparate materials of the everyday with the artist’s artful interference. Yet I would argue that a work like Bed (1955), one of Rauschenberg’s first in this genre, was in its time and still remains almost immediately accessible on so many levels—as autobiography, as a critique of Abstract Expressionism, as a work layered with intimations of sex and violence—that viewers don’t need a lot of explication to find a satisfying interpretation.

That, to me, is just not the same as throwing together a cartoonish portrait of Mozart with dangling liquor bottles and a nicely constructed plank of wood holding a pair of socks and some other detritus and calling it by the incomprehensible title “Geologic Amounts of Sober Time (Mozart Drunks),” as Marten did for one of her projects. And I don’t think any amount of wall text or critical exegesis is, as of this moment, going to change my mind.

I realize that over time, and if I have the opportunity to see the artist’s work in person, I may have a different reaction. I realize that time itself filters and clarifies the way we see artworks. And I further realize I may be contradicting some of my own earlier observations about keeping an open mind.

More likely it’s possible I’m simply becoming increasingly conservative in my responses to art. After 20-plus years of writing on the subject, and especially after starting and tending this site, I see how hard artists struggle to master their materials, to find a voice, to tap into a coherent vein that makes the work truly their own. And along comes some brash young newcomer, barely out of school, who walks off with a bushel of shows and honors.

Over the Thanksgiving weekend I had the opportunity to read and review a gorgeous book of paintings and verse called Morning, Paramin, a collaboration between poet Derek Walcott and artist Peter Doig. I’d seen a few of Doig’s paintings here and there, but had never had the opportunity to savor more than 50 of them, albeit in reproduction. That experience felt like sinking into the enchantment I savored in art books when I was a kid, with the added bonus of the evocative Walcott poetry. There were echoes in Doig’s pictures of earlier artists (Gauguin, Rousseau, Matisse), but he manages to conjure up modern magic with old-fashioned means—paint, canvas, brushes—and not much else.

Doig was nominated for but never received the Turner Prize and was nearing 50 before he scored a major museum solo. By then, the honors seemed well deserved.

I wouldn’t wish for art to keep mining familiar turf, or for young artists to shy away from new ideas, but I might wish that the clamor and prizes wait a few years before the so-called art world latches on to the next hot thing. Even a dead shark can look a lot better 25 years after its debut.

Top: Helen Marten, Brood and Bitter Pass (2015), photo courtesy Greene Naftali

Ann,

The New Bafflement!!! I love it!!

The Sculpture Center seems to be embracing both Marten & Gentzken. I feel so withdrawn from this aesthetic and conversation but I keep waiting for a critic that embraces it to have a convincing argument for it. Haven’t seen it yet!!

Post-Trump-slump in London, I came across a show in the Serpentine Sackler Gallery of work by someone I’d not taken in before. The large space was filled with the delightfully complex works of Helen Marten. She has mastered her materials and many they are; the finish, colour, texture, and scale are tied up with ideas in the legacy of art and add up to something new. At that point I hadn’t realized she was a nominee for the Turner Prize. And when she received it she shared it with the other artists, as she did with the Hepworth sculpture prize, commenting that she felt “frankly a little embarrassed about it all”. This young woman is a genius, in my opinion, and we will see and hear more of her.

I would have gone back to see the show again, except it was the second to last day…it lifted my mood considerably. Though I took some photos of the work, to remind me, it can’t be captured by photographs.

I vote for Doig!

I wish younger artists would be given a chance to develop before notoriety hits them. The attention Marten got as a 25 year old must have been amazing for her—but how could someone that young possibly handle it? I’m guessing it could end up being a burden or at the very least cripple the ability to explore, grow and mature without all that baggage.

Not to mention overturning the prospects for “mature” artists to get the recognition they deserve. There are plenty of deserving & overlooked older artists out there. Instead of giving a handful of artists all the attention over and over and over or picking up these young blazing stars, the art world would be much enriched if opportunities were opened up for artists who’ve put in their time and stuck with it to develop their own voice.

And that’s part of what Vasari21 is doing! Thanks Ann.

Brava! Your writing is brilliant!

No “crisis of criticism” here!