Blather and Bloat

Part One of Some Random Thoughts on Writing About ArtThe question I have been asking myself: What makes for good art criticism? Or just good writing about art in general?

First of all, it’s not a bad idea to find the right words. Recently I read an online critic who declared, “I am heading out to see a few shows and write about those that plague my mind.” Plague? Really? Meaning a potentially fatal malady, or, as the dictionary says, “to annoy, bother, or pester”? Why venture out in search of trouble, unless Bruce Nauman has something worth visiting? Maybe he meant exhibitions that “haunt my mind” or “linger in memory” or even “seem worth noting.”

But pesky words aside, the real purpose of any nonfiction—whether it’s criticism, an editorial, an essay, or reporting—should be to seduce, engage, and inform. And, if possible, please, please try not to befuddle.

I ask your indulgence, readers, in presenting segments from two long-ish paragraphs. Both writers are talking about the discomfort, sometimes extreme, that accompanies encounters with the new and unfamiliar in art. Think of this exercise as somewhat like Art 101: compare and contrast.

“…I know that images can alter the visual construction of the reality we all inhabit, can revise the expectations that we bring to it and the priorities that we impose upon it—and know, further, that these alterations can entail profound social and political ramifications. So, even though I am an art critic now and occupationally addicted to the anxiety of change, I cannot forget that there should be more to it than that. Simply, there is change, and there is change; and, when that previously redolent signifier takes on the innervating aspect of Brownian agitation, and that previously challenging occasion for upgrading the efficacy of one’s critical practice becomes a demand to practice it as preached, one can become a bit contemplative about the whole endeavor—about connecting the dots, as it were, with regard to objects that present themselves as strategized invitations to cite those talismanic theoretical texts that inspired them in the first place.”

“…[O]ne thing has not changed: the relation of any new art—while it is new—to its own moment; or, to put it the other way around: every moment during the past hundred years has had an outrageous art of its own, so that every generation, from Courbet down, has had a crack at the discomfort to be had from modern art. And in this sense it is quite wrong to say that the bewilderment people feel over a new style is of no great account since it doesn’t last long. Indeed it does last; it has been with us for a century, and the thrill of pain caused by modern art is like an addiction—so much of a necessity to us, that societies like Soviet Russia, without any outrageous modern art of their own, seem to be only half alive. They do not suffer that perpetual anxiety, or periodic frustration, or unease, which is our normal condition, and which I call ‘The Plight of the Public.’”

The first paragraph is from Dave Hickey’s essay “Prom Night in Flatland,” included in a slim volume called The Invisible Dragon: Four Essays on Beauty, published in 1993. The second is from Leo Steinberg’s “Contemporary Art and the Plight of Its Public,” first published in 1962 and ten years later collected in Other Criteria.

I was, I confess, working hard, reading and rereading the essays in The Invisible Dragon to grasp the meaning and substance of Hickey’s discussions of “beauty,” but soon I was stumbling grievously in paragraph after paragraph. I balked a bit at “Brownian agitation” (wasn’t that high-school chemistry? quick…Google it!) and then almost gave up at “talismanic theoretical texts.” What texts? Which of those are particularly “talismanic” and why? A couple of paragraphs later, I was damn near snorting: “Today, for some reason, we remain content to slither through this flatland of Baudelairean modernity, trapped like cocker spaniels in the eternal, positive presentness of a terrain so visually impoverished that we cannot even lie to any effect in its language of images….” And so on and so forth.

Unless one is a snake, how does one “slither” through a flatland? And then we get to the pups: Why cocker spaniels? Why are they trapped? What am I missing? Is it that dogs seem to live only in the present? Cocker spaniels more so than other breeds? Why do I have to stop reading to puzzle this out? Block that metaphor!

I have no such problems with the late Professor Steinberg, who deserves that “redolent signifier” for the grace of his prose, the breadth of his learning, and his stance toward his readers, which does not condescend, bewilder, or assume too much erudition. His mind ranges easily and nimbly through essays on Pollock, de Kooning, Monet, Picasso, and Jasper Johns (the last is must reading for anyone who wants to understand the mental gymnastics of a brilliant critic and art historian). His arguments unfold elegantly and lucidly, and are as accessible to the lay reader as to anyone intimately familiar with the terrain of art and art history.

But Hickey presents difficulties, first and foremost with the choice of words and other irksome elements of English prose—metaphors, qualifiers (“suboptimal secular agenda”), unnecessary interjections (“it seems,” “I think”) and continuing through the occasional casually dropped WTF? moment, possibly tossed in to remind us of just how cool Dave is: “I saw Robert’s images for the first time scattered across a Pace coffee table at a coke dealer’s penthouse on Hudson Street….”

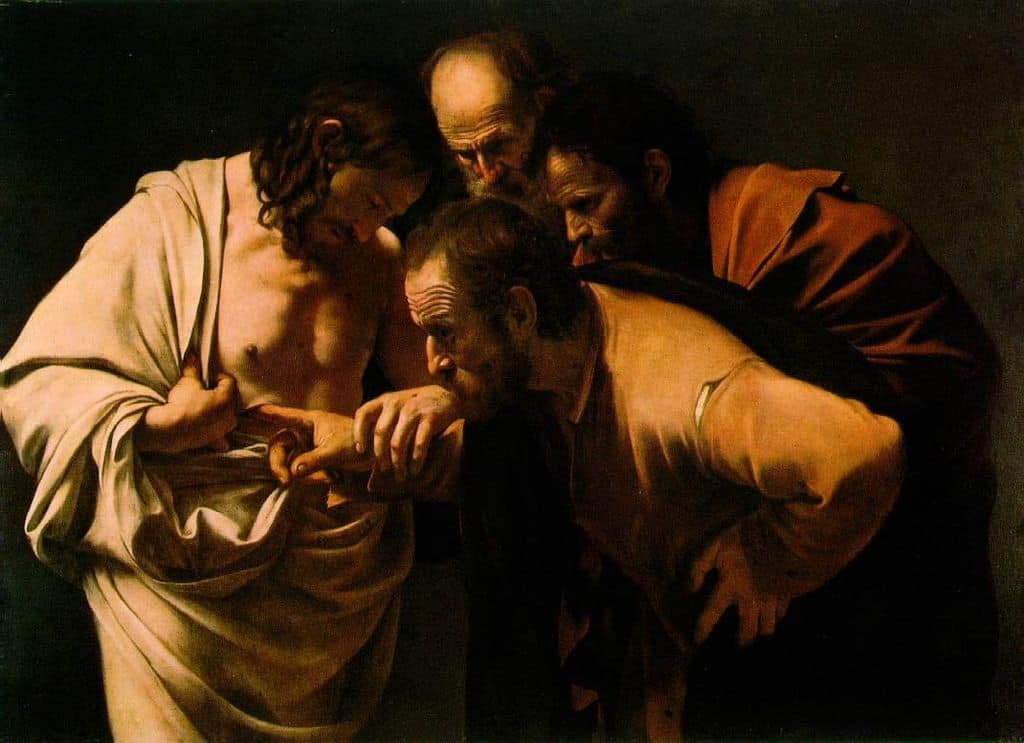

There is, however, one essay in this little collection that may be worth the effort. Called “Nothing Like the Son,” it neatly weaves together Caravaggio, Shakespeare, and Mapplethorpe in an attempt to describe a transgressive space, a “vertiginous category of experience to which art belongs—and we rather wish it didn’t.” I would argue that Shakespeare’s X Folio and Caravaggio’s The Incredulity of Saint Thomas no longer have quite the power to shock as Mapplethorpe’s photos, two of which are reproduced here—one of a man inserting his finger into the tip of his penis, and another with his arm partly submerged in another man’s anus. I can’t predict, but I would argue further that the Mapplethorpe photos will leave viewers gasping for generations to come. (I first saw them in 1988 and blanched all over again at the reproductions here; in fact, had to cover them with my hand to continue reading.) Even as they are given a certain legitimacy on the walls of galleries and museums, even as they are condemned by Jesse Helms—the anti-Christ and therefore the seal of approval for the liberal art-loving public—the photographs will retain their uneasy potency far longer than Caravaggio or the Bard. But maybe that’s his point.

I am not completely sure, as I got a little lost slithering through those flatlands.

Ann Landi

Photo credits: Jasper Johns, Numbers (2011), bronze, 19-3/8 by 37-1/2 inches | Caravaggio, The Incredulity of St. Thomas (1601-02)

Ann, this essay is a fine example of what I love about your work: clarity and common sense delivered with sly humor. You are a veritable treasure, my friend!

Great article Ann. Reading Hickey’s book out loud became a college drinking game in regards to his use of the word ‘quotidian’. I should read it again but without the tequila…

Ann, I do like David Hickey’s writing for the most part, but you are right, I hated that paragraph you shared, made little sense and I was bored with it very soon after starting it.

I felt lucky and honored when Dave Hickey accepted my request to be a facebook friend. I felt just as grand when I could take no more, deleting him from my friends list a few months later.

I like you very much, Ann. You don’t take any shit and see it clearly. A rare breed in this kiss ass society.

Great to see someone intelligently discussing the art of writing and contrasting affected, dare we say Euphuistic, prose with writing that is clear and concise. Insightful, as always, Ann.

I am so behind in my reading, and finally got to this and am in complete agreement. I think Leo Steinberg a brilliant writer, admirably clear when discussing complex subjects. Hickey not so much, an unfortunately in love with the sound of his own voice.

Nice post. I learn something more challenging on different blogs everyday. It will always be stimulating to read content from other writers and practice a little something from their store. I’d prefer to use some with the content on my blog whether you don’t mind. Natually I’ll give you a link on your web blog. Thanks for sharing.

Reading Ann Landi is like a walk through a gallery in conversation with a good friend, a friend who has looked at and studied art her entire life. Ann does not talk down to her audience. She writes clearly, directly, and authentically.

What makes for good art criticism? Or just good writing about art in general?

A good example of quality art writing would be just about any text by Ann Landi.