––––

Artists and Critics: Part One

Sometimes the best way to respond to a bad review is to take a long walkBY ANN LANDI

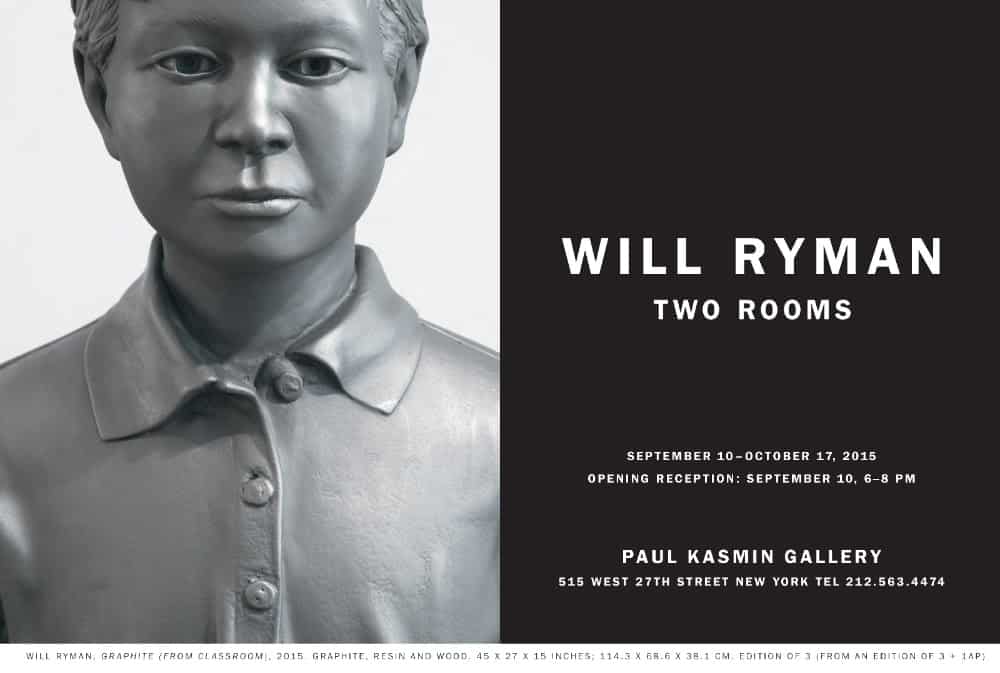

About ten days after the September 2015 opening of Will Ryman’s latest show at Paul Kasmin Gallery, ARTnews reporter and critic Andrew Russeth delivered a sharply negative appraisal in the online edition of the magazine. He called the two-part installation, which took as one of its subjects the famed photo of President Obama and his national security team watching the take-down of Bin Laden, a “season-opening disaster” and accused the artist of “turning a complicated moment of national vengeance and political theater into pure kitsch.” The review amounted to a two-paragraph, no-holds-barred dismissal of three years’ worth of work, with nary a word of praise.

I spoke to Ryman a week later. How did he feel about the slam? “It hurts, but I tend to get over these things quickly,” he replied. “If I’m not happy with the work, if something bothers me, then it’s worse. This felt almost like a personal attack, and there’s nothing I can do about that. Of all the openings and artists in Chelsea, maybe I should take it as a compliment to be singled out.”

Criticism, whether online or in print, in a prestige newspaper or a small-town tabloid, can wound, provoke, unsettle, and elate, but it is part and parcel of that artist’s life. How you handle it depends a lot on your attitude, your resilience, and possibly your age.

Early in her career, in the mid-to-late 1980s, Petah Coyne was riding a wave of enthusiasm for her offbeat and ambitious sculptures, hailed as “magical effigies” by critic Michael Brenson in the New York Times. Coyne had garnered nothing but glowing reviews—along with Guggenheim and Pollock-Krasner grants—for her work in alternative spaces and university galleries, and was working towards her first solo show at a commercial gallery, in 1989. “The positive responses to my work gave me the confidence to continue to be experimental with industrial materials, black sand and oil, and other less common mediums,” she says.

Then came what Coyne interpreted as a “really mediocre” review from the same Times critic (we both looked at it later, and realized it was not half so damning as she’d thought 26 years ago). “I was stunned, I never expected it. I had a lot of confidence in the work. That following Monday we were installing my show at the Brooklyn Museum, and the pieces were huge, the largest nineteen feet high and nine feet wide. It was a stressful time, and I suddenly felt sick at heart.”

Left: Untitled #633, 1989, © Petah Coyne, Courtesy of Galerie Lelong, New York , Photo by Wit McKay

Right: Untitled #638 (Whirlwind), 1989, © Petah Coyne, Courtesy of Galerie Lelong, New York , Photo by Wit McKay

A good friend came to the rescue, coaxing her out for a long walk around Manhattan. She was feeling slightly better by the time she had to go to her gallery in SoHo for a meeting, when her dealer at the time informed her, “I don’t think we’re going to be showing you again. Everybody that was planning to buy the work is canceling.” (He later changed his mind.)

It was a roller-coaster day, capped by Coyne’s return home to a call from a collector, who told her, “Good for you! You got a lousy review! That means you’re a fantastic artist and we’re going to keep buying your work. If everybody understands you, and you’re doing something everybody gets, what good are you?” The collector purchased two works and continued to be a loyal supporter.

Still more happy surprises were in store over the next few days. While Coyne was installing at the Brooklyn Museum, a successful sculptor acquaintance gave her a blank check and told her to “fill it in for the amount that you think you will need over the next few years, so that you can get back to your studio and keep producing the works you need to make.” Another artist friend offered to store the work until it could be sold (which it did, toward the end of the ’90s). And then, a month later, Michael Kimmelman, who was soon to become chief art critic for the Times, gave her installation in Brooklyn a short, but glowing, review. (“Ms. Coyne’s works seem to gain in potency as they increase in scale,” he wrote.)

The seesawing of emotions engendered by that one review, the outpouring of support from friends and collectors, and her own powerful reactions offered Coyne the opportunity to reflect on how she approached the art world. “It threw me into experimenting further with my own work,” she says, “and it made me want to continue to be generous and even more supportive of other artists. I became involved in organizations with other artists to help foster artistic communities, and got more involved in studio visits and groups where we gave feedback on one another’s works.

“I was very naive when I was starting out,” she adds. “I assumed the art world was only there for support. But it took those initial criticisms to help me dig further into my practice and explore my intentions, which in the end helped me come to an even purer idea of why I was making art in the first place.”

Dumb and Dumber

In the case of Russeth, Brenson, and Kimmelman, one can at the very least say that the critic knew the playing field and was doing his job. Los Angeles artist Mona Kuhn (look for a podcast with her in the weeks to come), whose specialty is photographing the nude in unexpected and often breathtaking ways, recalls a critic from the L.A. Times who “just did not seem professional at all,” she says. “She came into the gallery, was asked if she wanted more information, but declined. Afterward, without doing research into my work, she wrote an underwhelming review.” The critic claimed Kuhn’s models were far too beautiful, a sign of immaturity in the photographer. She also got her facts wrong, claiming Kuhn was born in Mexico, when she is of German descent and born in Brazil. The artist says she “politely” invited the critic for a studio visit, to give her a chance to see more work and talk about her career. The invitation was declined twice, “I tried a third time to meet, this time on neutral ground, but was again declined,” recalls Kuhn. “You can tell someone is not okay when they hide.”

The experience “did not affect my work directly, but it had a distancing effect on me,” she continues. “I stopped reading reviews or respecting people who are obsessed by them. Of course I continue to read certain critics, but only those I’ve learned to trust over time, and whose insightful and at times edgy writing is of value to the art world.”

Sometimes a review may be so bewildering it’s difficult to know whether the writer is damning or praising the work. Paul Pascarella, a painter friend in Taos, recently called to ask me to read a full-page critique of his show in a local arts magazine in Santa Fe. “I don’t know whether this is good or not,” he said. “Call me back and tell me what you think.” I read the review twice, following the writer’s sustained metaphor that Pascarella’s painting was a contemporary twist on Mannerism, his work was to Abstract Expressionism as Bronzino’s was to the lofty style of the High Renaissance (a better analogy would have been Rosso Fiorentino or Pontormo, since Pascarella’s gestural style has a great deal more energy than the highly polished froideur of Bronzino).

It seemed to me the writer was mostly eager to find a way to throw out as many names as possible in the allotted 600 words or so—including Giorgione, Baudelaire, Cézanne, Pollock, Helen Frankenthaler, Clement Greenberg, Arshile Gorky, Phillip Taaffe, Rex Rey, and Jimi Hendrix—and then lost any credibility completely when he offered a tired (and childish) burst of alliteration about “Pascarella’s painterly power punch.” That’s just dumb writing, and most sensible editors would have cut it. In the end he concluded that various “elements and approaches all peek out from around Pascarella’s current perfect pieces [and] who knows what they might come to mean.”

But the truly bewildering part came when I looked up the reviewer online. It turns out he is a painter too, of works I can’t imagine being shown anywhere outside an airport gift shop. They have as much to do with the dialogues surrounding post-Modernist painting as a Keane portrait does with, well, Bronzini’s brilliant portrayals of 16th-century Italian nobility.

“So what did you think?” asked Paul a few hours later.

“I think,” I said, “that you should not pay it much attention at all, but put in on your website. It’s a full-page review, the layout is handsome, and most people will stop reading after the second paragraph.”

Quick Tips:

- If you’re baffled or offended by a review, track down the critic and ask her to pay a studio visit so you can explain your work more fully. You never know….you might make a new ally.

- If a review seems confusing or hard to understand, it may simply be badly written. Some people in my line of work rely on an arsenal obscure words to sound smarter than they are.

Photo credits: A Walk at Dusk, Caspar David Friedrich (German, 1774 – 1840), Oil on canvas. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program. Untitled #638 (Whirlwind), 1989, Petah Coyne, Courtesy of Galerie Lelong, New York, Photo by Wit McKay Untitled #920 (Murasaki Shikibu and Sei Shonagon), 1997-98, Petah Coyne, Courtesy of Galerie Lelong, New York, Photo by Wit McKay

This piece reflects so well one of the things I love about Ann’s mind and writing – diamond edged and funny

Pumping Hendrix’s “Purple Haze” into an exhibition of Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino–now there’s a trip!

I truly appreciate a website with important knowledge for artists. This is a very competitive world with little information for single artists to know and understand how to survive.

I would love to hear about how to thrive in our own towns and sponsorships.

I’m very interested in learning the truth about Art Fairs and Art Galleries, art contests and associations as it seems the population of art critics is growing and everything gets too expensive for the artist.

Thank you for sharing all these subjects with us.

Cristina

As I delve slowly (third article) into this delicious website, what reveals itself is not only the breadth of talent and the immense population of talented working artists, but also Ann’s love of art and artists.

Having removed myself from New York City’s frenetic pace, and sometimes ‘nature, red in tooth and claw’ quality, I find life to be sweeter and the fight or flight adrenaline easing from my psyche. There are many of us hither and yon.

Chelsea is not the cosmos. Siesta Key is paradise; Sarasota has some awful work balanced by exquisite work.

Hendrix. Forever great. Just my opinion.

Excellent topic and article and thanks to the artists for sharing their experiences.

Reviews about one’s artwork are always a bit scary, since you never know what will come out in print. Sometimes it’s well written and insightful and other times not so much.

I love your advice to this artist:

“I think,” I said, “that you should not pay it much attention at all, but put in on your website. It’s a full-page review, the layout is handsome, and most people will stop reading after the second paragraph.”

In general this is true of art reviews. People tend to look at the pictures, read only part of the review if it’s long and mostly remember that the artist was reviewed, which is the important thing. Better to get your art out in the world, then to remain anonymous. Thanks for lifting the veil on another aspect of the art world!

Ann, Thank you for this article of support and encouragement! A good reminder that even the best of the best get mediocre reviews from time to time. Also, helpful to read how artists looked for the upside.