Sanctioned Spaces

Living with the most important legacy of a famous father and his equally famous wife: the studiosRobert Motherwell, my father, purchased our home the year I was born. My earliest recollection of entering his studio is when I was a toddler. We lived in a brownstone on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, which had a flagstone patio—a postage stamp of outdoor magic—where my sisters and I loved to play. But to get there, we had to go through his studio, this sacred yet foreboding ground in which we were never allowed to loiter without adult supervision. I had no idea why it was so “special” but I was terrified of violating such sanctioned space.

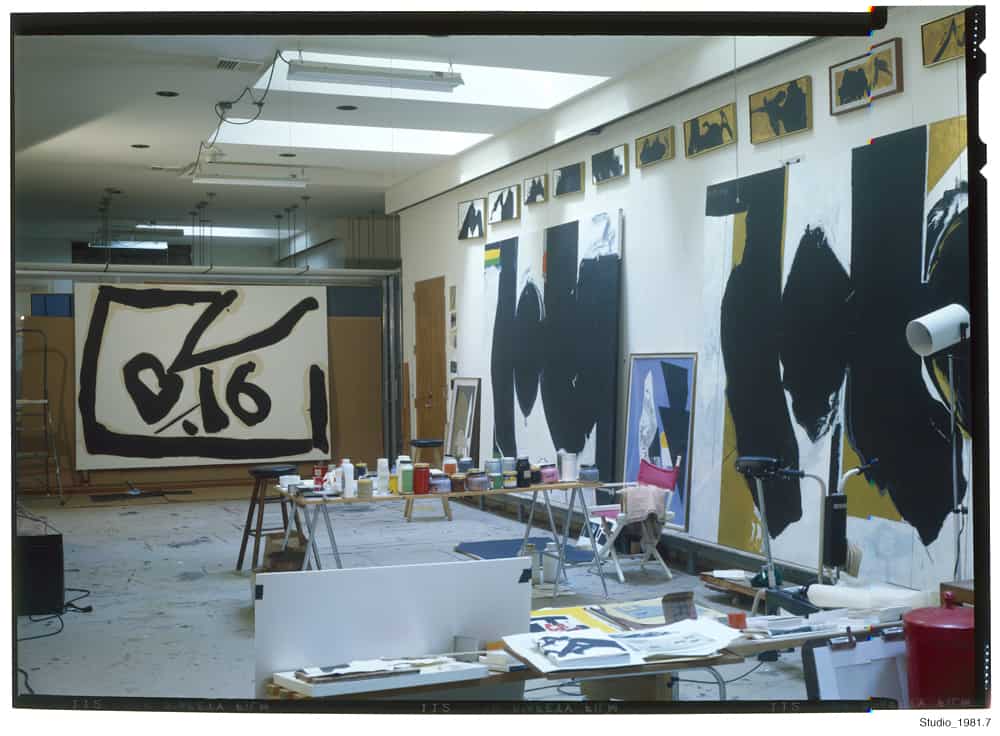

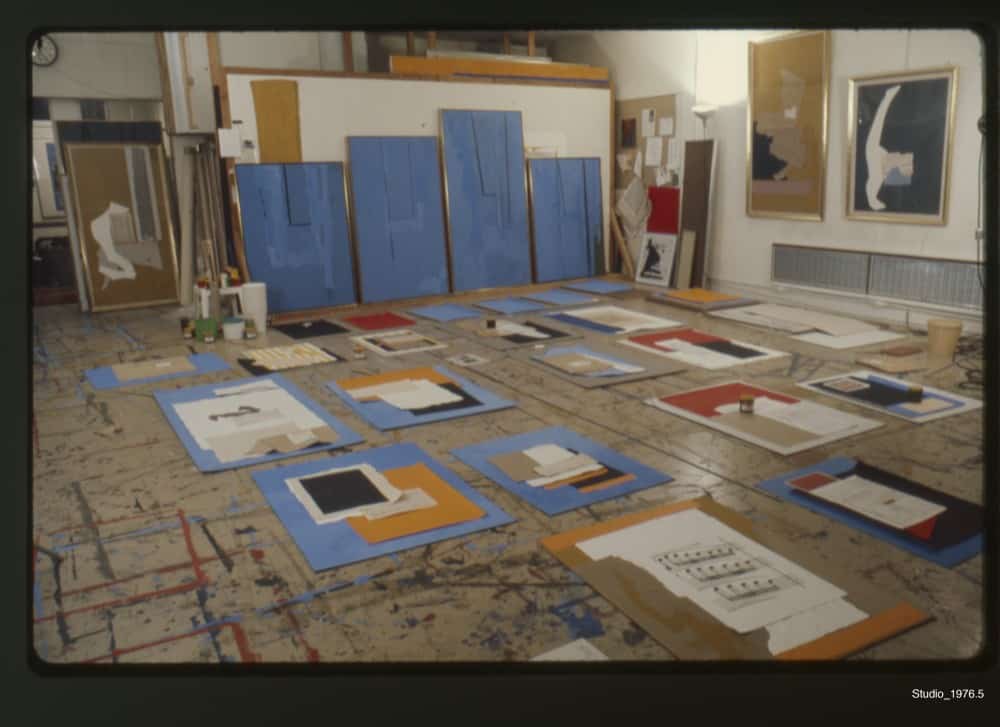

Robert Motherwell’s painting studio, with rolling racks, in Greenwich, CT. Photo courtesy Dedalus Foundation.

As a collage artist and painter myself, I am all too understanding of why Dad’s studio was so off limits—paper tentatively but meticulously placed, yet unglued, the night before—how easily in our rush to escape to our patio playground we might have scattered an entire night’s work!

When I was five, my father married Helen Frankenthaler. She had a studio outside of our home, and I recall thinking “how nice” it was for her to leave our basement for Dad. Later I realized that she knew the business of her career was far better served outside the home, away from children, dogs, and the daily routine. Extremely organized and meticulous, she became a mentor to me long before I realized it. I remember as a teen thinking, how odd to call her on the phone, only to have it answered by her studio assistant. Why couldn’t she take the call herself?

My stepmother, Helen Frankenthaler, knew the business of her career was far better served outside the home, away from children, dogs, and the daily routine.

Every year we summered in Provincetown, MA, a small fishing village at the tip of Cape Cod and a thriving artist and writer’s colony. Dad chose this location for its serious yet unpretentious artistic community. It was also a wonderful place for children to romp around largely unsupervised, and a good alternative to summer camp.

My father and Helen’s studios were above each other in an old barn, now home to the Fine Arts Work Center (FAWC), a residency program for artists and writers which Dad co-founded. After many years, Dad was able to purchase waterfront property, where he built our home, the three-story “Sea Barn,” with studios on the top two floors and living quarters on the first.

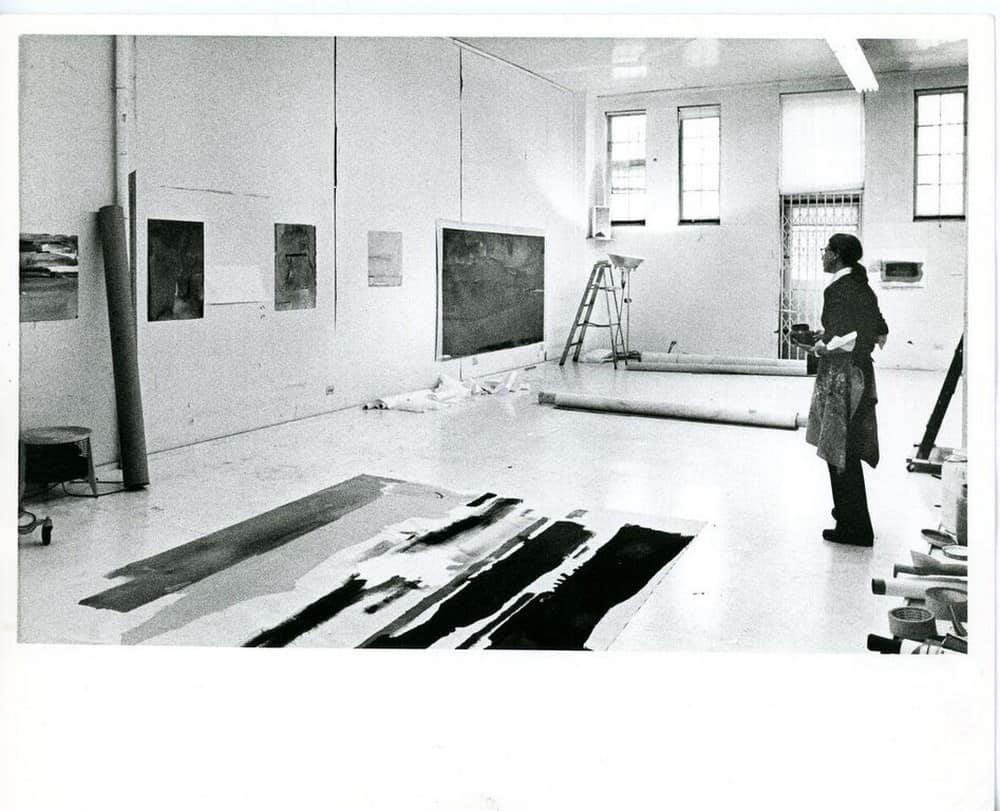

Helen Frankenthaler in her East 83rd Street studio in New York, September 1975. Photographer: Edward Youkilis. Helen Frankenthaler Foundation Archives, New York, NY.

Once on my way home from college, I visited Helen (she and Dad were now divorced) at her East 83rd Street studio, a much larger space than when she first married my father. It was then that it dawned on me what a “factory” she had created and why it would have been impossible for her to have a studio at our home. It was not just a place to paint—it was zoned as a full-blown enterprise replete with studio assistants, office staff, and often visiting artists, students, gallerists, or curators. It was both awe-inspiring and intimidating to me because I was beginning to take seriously my own future career as an artist.

After their divorce, Dad purchased a carriage house in Greenwich, CT with living quarters upstairs and studios downstairs. His work space was separated into zones similar to Helen’s. It was divided, more or less, into seven studios in all, each for different purposes: painting, framing, printmaking, collage, and displaying. The largest studio, where he did most of his painting, was lined with custom racks that rolled out from the wall to display paintings for dealers, critics, and collectors. For storage, they were simply rolled back into the wall.

Often when I visited from college, I couldn’t wait to get to his studio so that he and I could critique works-in-progress or recently finished paintings. “Which is your favorite painting and why?” he would ask. It was not an unfamiliar question since both Helen and Dad asked this whenever I attended their openings. I was quite comfortable by this time discussing my father’s work with him. He would often say, “You really get it!” We would also discuss how my work was going when I was in college and after. Learning the “language” of painting during these visits helped me develop a critical eye, one that continues to inform my work today.

There were administrative offices as well, and an open space for dining with his “crew,” as he called his staff, for debriefings during lunch. They tackled the administrative and logistical aspects of his business so that Dad could paint without interruption at night. He would escape the busy-ness of the day and paint from eight in the evening to around two a.m.

Frankenthaler’s studio was both awe-inspiring and intimidating to me because I was beginning to take seriously my own future career as an artist.

In the mid 1970s, having graduated from college with a degree in painting, I moved to a loft in SoHo at a time when it was more affordable for artists to live and work there. I was painting on a large scale, and my studio had high ceilings with separate living quarters. I took immediately to the convenience of working from home.

In 1989, I relocated to Connecticut to be closer to my father, who had become ill, and so that he could have a relationship with his only grandchild, my daughter, Rebecca. In 1998, now divorced, and with my father deceased, my daughter and I moved to Cambridge. I had not painted in several years, partly because being a single mom had become my full-time job, but mostly because the model I had of an art career, absorbed from Helen and my father, was beyond intimidating.

As the necessity to make art kept percolating, I came to terms with the fact that I needed to make art again and on my own terms. I used the basement in our townhouse as my studio to make much smaller and more intimate collages and paintings. That worked well for several years, but when I returned to painting on a big scale, I needed more space.

I may never achieve the renown Helen and my dad enjoyed, but I can work in my own voice, which grows ever more distinct from my earliest influences.

Not yet sure I could adapt to having a studio away from home—with no kitchen or other conveniences—I was reluctant to leave. Eventually I made the move, and took a studio about 15 minutes from home in a large warehouse converted to work spaces for artists. Now I consider those “conveniences” as distractions, and I am free to focus entirely on my precious and limited time in the studio with new perspective. Most importantly, to my delight, there is a community of artists in my building. And through this community, I have found a new home.

I may never achieve the renown Helen and my dad enjoyed, but I can work in my own voice, which grows ever more distinct from my earliest influences. In my work, I continue to be amazed with the images and mysteries of creation—like the oceans and skies in changing weather, Hubble-type images of the universe, and my own physicality during the painting process. It is the space that I seek to capture and the three-dimensional energy that defines it. This requires the eye moving off the edges of my canvas while bouncing back through its surface. Unlike the flatness in my father’s paintings or the landscapes of Helen’s, my pictures explore a complex space which yields marvelous surprises that carry me in directions I cannot anticipate. It is like a dance with a creative partner gently leading me into moves I have not yet experienced.

Born and raised in New York City, Jeannie Motherwell inherited a love of painting from her father, Robert Motherwell, and stepmother, Helen Frankenthaler, two pillars of mid-century abstraction. She studied painting at Bard College and the Art Students League in New York. Continuing with her art after college, she became active in arts education at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, CT, until relocating to Cambridge, MA, where she worked at Boston University for the graduate program in Arts Administration from 2002 to 2015. Her work has been featured in such publications as Hamptons Cottages and Gardens, Avenue, Home & Design, Provincetown Arts Magazine, and Provincetown Magazine and is in public and private collections throughout the US and abroad. More about her work can be found at jeanniemotherwell.com

Born and raised in New York City, Jeannie Motherwell inherited a love of painting from her father, Robert Motherwell, and stepmother, Helen Frankenthaler, two pillars of mid-century abstraction. She studied painting at Bard College and the Art Students League in New York. Continuing with her art after college, she became active in arts education at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, CT, until relocating to Cambridge, MA, where she worked at Boston University for the graduate program in Arts Administration from 2002 to 2015. Her work has been featured in such publications as Hamptons Cottages and Gardens, Avenue, Home & Design, Provincetown Arts Magazine, and Provincetown Magazine and is in public and private collections throughout the US and abroad. More about her work can be found at jeanniemotherwell.com

Ann Landi

Photo credits: Edward Youkilis (Helen Frankenthaler’s studio); Jim Banks (Jeannie Motherwell in her studio)

Loved this article! I enjoyed hearing about the working life not only of her famous parents, but how she created a working artistic life for herself. Bravo!

Bravo! Beautiful portraits of your father and stepmother and the relationships you had. Wonderful to learn of your own development, building of your own voice and imagery as you also cherish the context of your childhood. The use of space, so well described, evokes how each of you worked. I am glad to know that and will enjoy reflecting on it. Thank you!

Thank you for this lovely behind the scenes of life with these two amazing famous artists. Jeannie’s work is wonderful and good for her keeping at it until she found her own way. I am off to check out her website.

Fabulous! Thanks so much for sharing!

What a wonderful description of the past and present and glimpse of the future!

Brava Jeannie!!

I really enjoyed this article Ann, great story!

Wow, an amazing interview that makes three artists come alive!

I really enjoyed this article very much and your good works, keep up, there will come one day, beautiful!

It isn’t often enough that we are privy to the day to day influences of how an artist’s lifestyle lay ground for their children and what perspective holds its highest place in the child’s memory. This is one family’s story that happy I did not miss. Am impressed how Jeannie has captured eras of valuable insights in a handful of paragraphs. Clearly her ability to capture space reached beyond 2-dimensions. Thank you.

Thank you Jeannie for your candidness.

I enjoyed this window into a sacred space and life.

How does one make a large clayboard surface? Love your work. Love to work on clayboard but only can buy small. Also love the asphaltum color.

I have them made by Ampersand. I do not make the claybords myself. you can order from dick blick up to size 48 x 48″ I believe. hope this helps!

Congrats Jeanie!! Great article too!

Such an inspiring story, thank you for sharing Jeannie, I fully understand the need to develop your own voice and that you did!

Best wishes to you always.