Several years ago, ARTnews ran a feature called “Ripe for Rediscovery,” polling curators, artists, and critics about which names had been unfairly lost in the shuffle of art history. Some of those who surfaced—Robert Irwin, Giovanni Boldini, and Rafael Ferrer—were not all that forgotten in 2010, but others were completely new to the magazine’s editors. The whys and wherefores of the various vanishing acts remain mysterious. “Careers of artists are as unpredictable as life itself,” said Julian Zugazagoitia, director of the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City. “Very few careers are sustained on a constant level, and sometimes artists need time off to refocus. There are also interesting artists who just somehow never connect—with a dealer, with the public—but they accumulate a large body of work.”

When I ran across the name Lee Lozano in an excellent new biography of dealer Richard Bellamy, it occurred to me that “Ripe for Rediscovery” would make a compelling occasional feature for Vasari21 (especially since I reviewed a book about the artist a couple of years back….and had completely forgotten about it!)

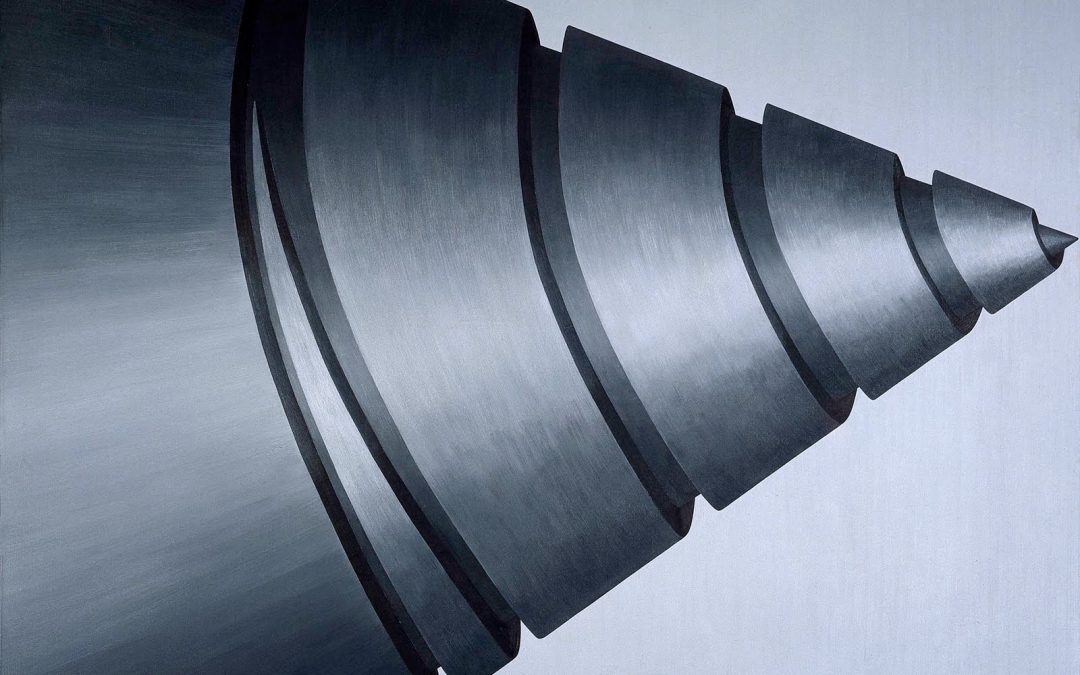

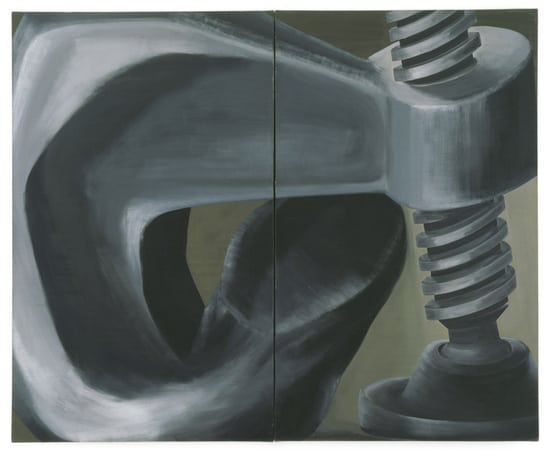

Lozano was born Lee Knastner in Newark, NJ, in 1930, and came of age in the late 1960s New York art scene, a heady time when Pop, Conceptualism, Minimalism, Land Art, and Fluxus converged with socio-political upheavals in the nation at large. She studied at the Art Institute of Chicago and was briefly married to an architect named Adrian Lozano. Her earliest paintings, as New York Times critic Roberta Smith noted, “featured a robust messiness, distorted close-ups of the body, intimations of violence and suggestively exaggerated images of tools.” But within a couple of years she abandoned the cartoony images of breasts and penises and bad-girl titles like Let Them Eat Cock.

By the middle of the decade Lozano was making abstract works, a few of which were shown a year ago at Hauser & Wirth in New York. These were “insistently physical: dark, quasi-scientific distillations of force; taut-surfaced vectors in which pigment and pencil are felt as solid matter and concentrated energy,” as described in the gallery’s press release. In 1970 the virtually monochromatic and elegant paintings in her “Wave” series earned her a show at the Whitney—then a relatively rare accomplishment for a woman artist. In line with practices established by artists like Sol LeWitt and Carl Andre, who were among her circle of friends, the paintings started with self-generated mathematical systems. The artist then completed the works in a single “sitting,” whose production time ranged from a few hours to a grueling three-day uninterrupted session.

Concurrent with the “Wave” paintings, Lozano created a series of life-related actions, meticulously documented in notebooks. These included smoking grass for more than a month, then withdrawing from the weed; dialogue pieces with fellow artists; and boycotting other women as a means of improving communications with them (an act that predictably backfired). “The piece that resulted, which began with a simple gesture — tossing a letter from the feminist critic and curator Lucy Lippard onto a stack of unanswered mail — eventually escalated to the point that Lozano refused to greet or take phone calls from female acquaintances and insisted on having (male) guards at her shows, from which she tried to deny women access,” according to curator Alana Heiss, as reported in the Times.

Her ultimate action was Dropout Piece, a systematic and sustained extraction from what her biographer, Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer, describes as the “egocentric competition and self-promotion” of the art world. Virtually a recluse for nearly 30 years, she died in Dallas in 1999, at the age of 68.

“Lee wanted to be a bad boy very much,” Heiss told the Times. “Then she got irritated because she always a girl in the end.”

Ann Landi

Top: Ream (1964), oil on canvas, 78 by 96 inches. All images courtesy of Hauser & Wirth.

Great idea for a series of posts!