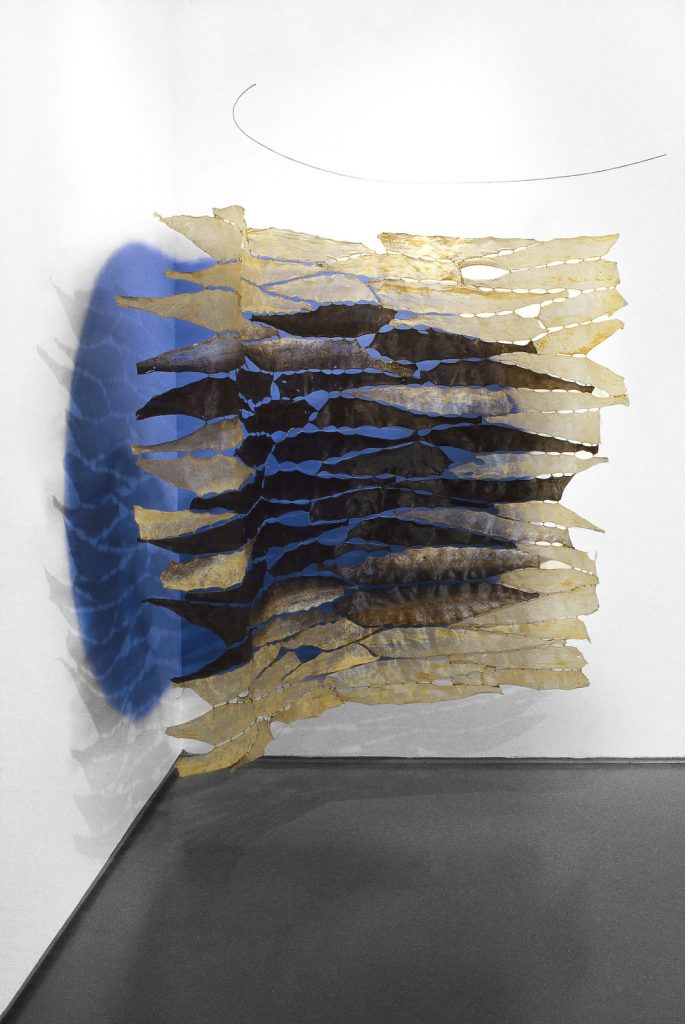

Synchrony (1983), deer hide, willow limbs, 67 by 57 by 75 inches. (Collection: Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY)

In 2011-2012, Carol Hepper spent a year-long residency at Park Avenue Armory, the venerable 19th-century building on New York’s Upper East Side that once served as home to an elite military regiment. The landmark was undergoing extensive renovations as part of its rebirth as a contemporary arts center, and Hepper discovered a way to make use of furniture that was on its way to the dumpster. A sideboard and a small cabinet (neither of any real historical value) underwent a transformation through the addition of branches, foam, fur pelts, and blown glass, morphing into a hybrid of the genteel and the untamed. “The bison lives on in the transformed furniture of the Armory,” one writer rather fancifully observed when the work was exhibited. “Indeed, this cabinet which is not quite fully fauna might canter away from the clank of regimental swords and the clink of colonel’s cocktails in the Field and Staff quarters across the way.”

Vertical Void (1994), copper and steel, 68 by 47 by 52 inches (installed in the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis garden at the White House, Collection: Orlando Museum of Art, Orlando, FL)

Making use of what’s at hand has come naturally to Hepper at least since her twenties, when recollections of childhood filtered into her earliest works. Her great-grandparents were homesteaders in the Dakotas, and Hepper herself grew up on ranching land that was within the Standing Rock Sioux reservation. “I was born about 20 miles from where Sitting Bull was born,” she notes. “I went to school with Native American kids, and there was a real cultural mix. We absorbed ideas through osmosis, through the experiences of one another.”

In college at South Dakota State, Hepper had the good fortune as an undergraduate to find a mentor in Donald Boyd, a member of the Fluxus movement of the 1960s and ‘70s. (That same movement, channeling a spirit of rebellion and irreverence, also nurtured Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik, and Joseph Beuys.) “Don was involved and engaged and a remarkable artist,” she recalls. “He was one of the most fun-loving personalities I have ever known.” Boyd undoubtedly exposed her to ways of thinking about art that might otherwise have been hard to come by in South Dakota.

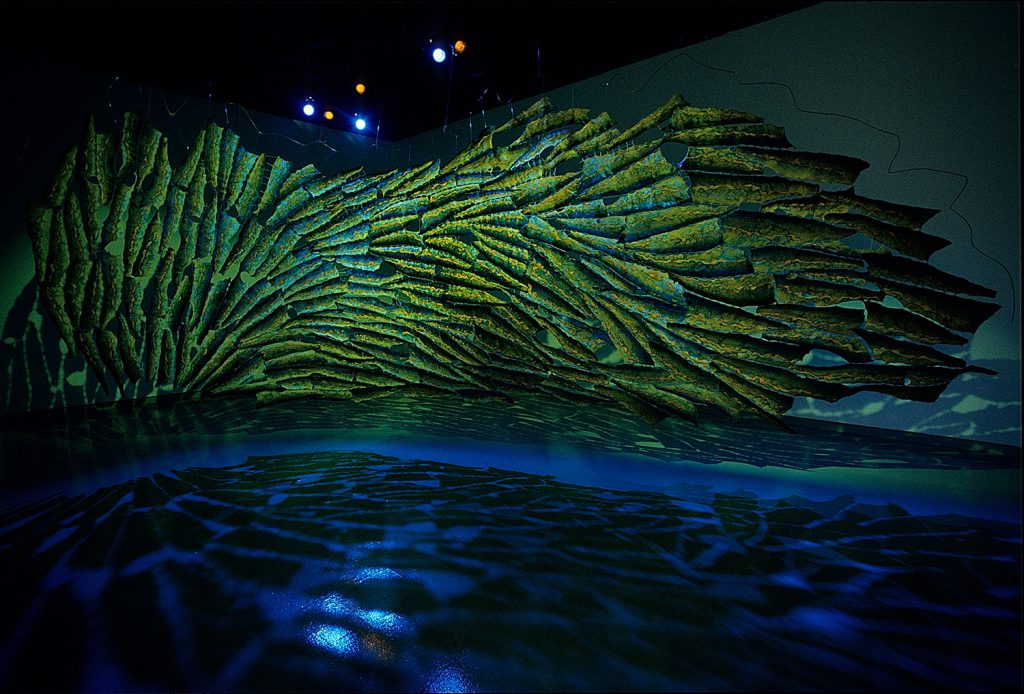

Island Blue (2000), salmon fish skins, fishing line,pigment, wire,, 7 feet 6 inches by 24 feet (installed in the Decker Gallery, Maryland Institute College of Art).

In the late 1970s, after graduation, Hepper was working as an art preparator and catalogue designer and teaching in St. Augustine, FL, when she fell in with a remarkable group of artists who included Jackie Windsor, Jene Highstein, Dickie Landry, and Tina Girouard, a good friend of Gordon Matta-Clark’s. These and others were part of a circle of artists collected by Norman Fisher, who bequeathed an enormous cache of works to the Jacksonville Museum of Contemporary Art.

By the time she returned to the family ranch in 1979—“to develop a real body of work”—Hepper had already found a footing in the advanced currents in the artistic circles of her time. While teaching at a local community college, she was also developing her own vocabulary as an artist. “I was doing a lot of reading,” she says, “and what I learned from writers was to create with what we know best. And so I worked with the materials that were around”—and those included animal hides, along with branches from willows and other trees that grew in the ravines. “I went to powwows as a child, and I got very interested in drumming, In fact, I played in a rock and roll band in high school. The drums were made from animal hides, and so my early work dealt with hides stretched on a framework made out of willow.”

She also discovered that the sculptures “had a percussive quality when stretched. They had the tautness of a drum,” she remembers. “I would take them outside to the prairie to photograph them, and the buffalo would move closer to check out what I was doing.”

Soon she was sending out slides and, with Boyd’s help, landed a show with five other South Dakota artists at 55 Mercer, an artist-run cooperative in New York. Within a few years she also caught the eye of Alana Heiss at P.S. 1, when it was first gaining notice as an exhibition space for young artists, and Diane Waldman, a curator at the Guggenheim, who chose Hepper’s work to be in a show called “New Perspectives in American Art.”

By 1986, the artist had moved to New York permanently, working in a studio on Fulton Street, not far from the fish market. It was there that she began making pieces with fish skin, a material that has remained part of her repertoire and has proved a source of strange and compelling beauty in paintings, sculptures, and a huge and stunning installation that incorporates fishing line, pigment, wire, and lights.

Over the course of a long career, Hepper has had shows across the U.S. and exhibited widely abroad, including in Australia, Liechtenstein, The Netherlands, Switzerland, and Spain. Through July, she is part of an exhibition in Bangkok called “Crossing the Dateline.” At different points in her career she’s had teaching gigs at some of the country’s most prestigious schools—like Princeton and Harvard—along with artists’ residencies at places like Pilchuck in Washington State, where she was introduced to the blown glass that appears in many of her recent sculptures and worked with master glassblowers Daniel Spitzer and Patricia Davidson. “I saw these pieces as more than objects,” she says of her experiments with glass. “But it took me a couple of years to figure out how I was going to incorporate them into sculpture.”

She (2016),19 assembled archival digital pigment print images on hahnemuhle photo rag, 73 by 38 inches

Her most recent three-dimensional works have continued to include elements of the great outdoors—tree branches, bison fur, and brightly painted jigsaw-like pieces that look to have been wrested from old buildings. And lately she’s been engaged with making large photo composites, assembled using up to 30 or 40 images of different sections of the sculptures. “It’s a way of rendering three-dimensional space in two dimensions while showing all sides of the sculpture simultaneously,” she says. “Initially I started going upstate and photographing woodpiles and cut wood, and also taking photographs of the landscape. But I soon realized with this way of working that I had a whole new means of looking at the sculpture. I could exhibit the work from a very different perspective.”

Carol Hepper with Rough Rider (2016),19 assembled archival digital pigment print images on hahnemuhle photo rag, 67.5 by 64 inches

Nonetheless, elements of her Western heritage—swags of bison fur, branches whittled to mimic antlers—appear even four decades after coming of age in South Dakota. And in titles like Squanto, Great Plains, Tumbleweed—one senses a yearning for those mythic wide-open spaces that probably never quite goes away.

Ann Landi

Top: Hepper’s sculptures from a residency at Park Avenue Armory. Left, Betwixt (2012) , file cabinet fragment, apple branches, hand-blown glass, bison fur, foam and pigments, 69 by 39 by 36 inches. Right, Armory Armoire (2012), mahogany side table, apple branches, hand-blown glass, bison fur, foam and pigments, 92 by 95 by 68 inches.

Wow nice work cousin! Amazing..

This is incredibly beautiful work. Brava Carol. I missed the article when first published and so glad to find it.

Not only incredibly beautiful, but also very intriguing. It incites my curiosity to see more. Thank you, Carol.